The crop circles of 2017

As we begin to anticipate what the crop circle season of 2018 might bring, Andy Thomas looks back at the circular events of 2017, which saw a renewed media attack on the phenomenon – and yet the coverage also helped draw attention to what turned out to be another fascinating year of wonders…

Attack of the Drones

Imagine this. A group of drone-owning “scammers” make, or commission the creation of, an elaborate crop formation. Once constructed, they fly their drones over it and take videos. The footage is posted online and large amounts of money are made from advertising revenue, thus justifying the whole enterprise.

Such was the scenario painted in the summer of 2017 as the one major piece of publicity the crop circle phenomenon received in the mainstream press, promoted as unquestionable fact. In a season where the UK received many ambitious and stirring designs in the fields, the media merely responded by reducing them to the level of ‘fake news’ click-bait. Derisory comments were included from the National Farmers Union (NFU) and the police saying that “crop circles posed a ‘considerable nuisance’ and members of the public should refrain from giving vandals the desired publicity” (Daily Telegraph, 13 July 2017).

The small-mindedness of the presumptions made in the near-identical reports which appeared across news outlets (presumably sparked by a press release from Wiltshire Police) reflect the paucity of journalistic imagination which surrounds unexplained mysteries in these times – and some crop circles do remain unexplained mysteries, however many might be made in the manner described.

As far as the veracity of the journalism goes, it should be noted that the same report claimed that a “recent circle” measured over “200 acres”. This would have made the formation an impressive 80,937 square metres, probably flattening several fields as far as the eye could see. Sensational though that would be, no such circle appeared. Likewise, the report claimed that the “true number” of crop formations is “thought to be higher as many farmers do not report them”. But very few farmers ever like to report circles anyway. Most are found by members of the public or circle-hunters and they are hard to hide in the relatively compact environs of the English countryside. And there was no “surge” of new crop circles in 2017; there were slightly less, in fact, than the previous year – and the formation shown on the Telegraph website (seen above) wasn’t even from 2017. All this was empty gibberish, in other words – as was the unchallenged assumption that all crop circles are man-made in the first place.

As for drone operators making significant amounts of money from online advertising, anyone who tries to get rich this way knows that one needs a lot of views to pay for anything much beyond petrol and batteries. Sadly, the circles are now of small-scale interest, partly because of coverage like this. Farmers are understandably concerned about damage to their fields from visitors to formations, but propagating nonsensical myths is not the solution. Is this the prelude to some kind of legislation that prevents people taking aerial photos of crop circles, by banning drone flights over fields? Let’s hope not, as their use has certainly enhanced our appreciation of these artistic wonders in recent years.

All this illustrates what the circles are continually up against. The vacuous and ill-thought-out attempts of the media to weaken interest in them has been a recurring theme for many years. Looked at positively, this latest approach speaks, perhaps, of the astonishing perseverance of this remarkable phenomenon. Having long ago exhausted any novelty in overt debunking, or making fun of the “wackier” theories, the coverage is forced to resort to verbatim reproduction of empty propaganda from authorities.

The Silent Coup

Such submission to authority is part of a worrying wider trend, of course, as Google and other search engines are demonstrating with the ongoing trend of pushing alternative topics so far down search pages that people are less likely to find them. YouTube’s unannounced but tangible bias against certain material, which either mysteriously vanishes or is boycotted by advertisers to the point of making it uneconomical to produce, is a further sign of a sinister silent coup against free speech and the flow of information. The claimed incentive to eliminate ‘fake news’ and worryingly ill-defined ‘extremism’ is quietly being used to close down legitimate alternative enquiry at the same time.

Were the ongoing attacks on subjects like crop circles over the past few decades simply an early testing ground to see how successfully undeniable phenomena and potentially important matters could be distracted from? If so it worked fairly well, to the point where even the majority of English people aren’t generally aware that crop formations are still appearing in their fields today.

One crumb of comfort that might be derived from the “drone scammers” stories of this season is that they have at least alerted some observers to the fact that patterns are still appearing, and indeed in numbers high enough that the police and the NFU have to issue statements about them.

Opening Weeks

Whether, then, the crop circles are the work of drone scammers or the mysterious ‘something else’ – extra-terrestrial, extra-dimensional, psychic or spiritual – that many believe explains the more ambitious creations in the landscape, how did this season unfold? With global numbers having receded in the last few years for reasons unresolved, we will deal first with the UK formations, which although also less in number still remained the central hub of the phenomenon and compensated with their remarkably consistent quality.

The first arrival, on 16 April (pretty much the usual opening period for English activity), lay in bright yellow rapeseed (canola) just below the famous stone needle which sits atop the crest of Cherhill in Wiltshire [pictured]. A crescent with a long spur leading to a slightly off-centre small circle, its crisp layout was distinguished by internal narrow standing paths, which provided a skeleton for the whole design. A further crescent in rapeseed appeared, accompanied by two small circles, two days later near Cherlington in Gloucestershire.

The first distinct mandala of the year (again in rapeseed) was found near Avebury on 22 April, a clean six-petalled flower with a central ‘cube’, seen as if in perspective. This was followed two days later by one of the more unusual designs of the season [pictured], on the top of Oliver’s Castle, near Devizes in Wiltshire (scene of the controversial video which shows a formation appearing, produced an incredible 21 years ago and still never fully explained for all the arguments). Although mostly comprised of empty space, this very wide ring, with no central motif, had 27 small ringed circles arrayed around its inside edge. This prompted speculation on forums, from it being a megalithic Moon-calendar to Mayan interpretations or warnings that it signifies a comet striking the Earth (several other designs this year were seen as sequels to all these themes). Given that many glyphs over the years have been interpreted as harbingers of imminent doom, the fact that we are still here suggests we probably shouldn’t worry too much.

A simple triangle of circles and paths around a small centre was found in grass at Madron in Cornwall on 28 April. The circle phenomenon was once far more active in Cornwall than it has been in recent years, so it was notable that this was the first of two Cornish events this season.

A Busy May

May can sometimes be a quiet month for the phenomenon after a prelude of early activity, but this year it confounded expectations (albeit mainly in its later weeks), with the UK producing nine formations, most of them noteworthy. These all appeared during weeks of frantic political activity in Britain as it prepared for an unexpected General Election, with a defending Prime Minister aptly named Theresa May.

A curious design in rapeseed on 4 May at Mere in Wiltshire, comprising two seven-circled arms either side of a triplet dumbbell, suggested some kind of swinging pendulum gauge – which may or may not have had something to say about the way the election would go! (May’s Conservative party expected huge success but a significant swing to Labour supporters actually reduced their majority, against all poll predictions.) The first grain pattern of the year, however, at Stitchcombe in Wiltshire on 21 May, seemed to promise a brighter future, being a striking motif of twelve smaller ‘sun rays’ within twelve larger ones [pictured].

Ancient sacred sites have long been attractors (or generators, in the earth-energy theory view) of crop circles, and one of this year’s more notable examples was the vesica piscis design which arrived just two fields away from the famous ‘giant’ chalk carving at Cerne Abbas in Dorset on 22 May. The giant is renowned for his rather large and uncompromisingly erect male member, so it was perhaps appropriate that the central motif of the formation was strongly suggestive of being stylised female genitalia… A fertility metaphor, perhaps, indicative of wanting to bring new life to world events? Or just a saucy wink from the circlemakers..?

Back in Cornwall, another notable English landmark received a crop glyph at Marazion near the sacred island of St Michael’s Mount on 24 May. A late rapeseed entry, it resembled a decorative glider plane, or flying fish perhaps. St Michael’s Mount is very near the Western end of the ‘Michael and Mary’ ley lines which are said to run across southern England from Norfolk to Cornwall – Avebury sits near its centre. This was one of two patterns to appear within sight of the sea this season, a fairly rare occurrence; the other appeared at Atherington, near Climping Beach, in West Sussex on 19 July and comprised a cross of multiple rings with a chequer-board ‘basket weave’ lay at its centre.

One standout formation [pictured] in May appeared at Alton Barnes in Wiltshire on the 25th, not far from another hill carving, the famous white horse that looks out across the Vale of Pewsey, which has seen so many crop circles in the last three decades. This was another cross, designed very similarly to the first UK event of the year at Cherhill, crisp with thin standing paths and rings delineating the overall pattern. Small standing centres punctuated each one of the four outer circles, with only the central circle laid entirely flat. A very neat lay was present overall and a smaller ‘fan’ of seven semi-circles adorned the side of one of the circles.

On 25 May, very near the Space Science Centre near Winchester in Hampshire, a Celtic cross with a central dartboard-like motif of segmented curved blocks appeared, while on 28 May Broad Hinton in Wiltshire saw the arrival of two complex formations in one night, one an elegant six-petalled flower of very thin paths and rings (with a small circle nearby), and the other a rather different five-pointed star studded with many tiny circles. On 30 May, at Chicklade, Wiltshire, a further six-fold flower was found, this time with much wider paths in the central area and six circles arrayed on the outside.

June Developments

The following month began simply on 3 June, near Avebury, Wiltshire, with a perfect ringed circle of the classic variety. Increased complexity followed as Oxfordshire entered the picture the next day with a striking six-fold emblem of multiple rings and circles at Ashbury [pictured below under ‘A Good Season’].

Back in Wiltshire, moving on from straightforward circular elements, the formation which arrived at Maiden Bradley on 9 June [pictured] recalled the more overt geometric play of earlier years. Essentially a circle with six semi-circles around it, clever standing areas implied a chunky pentagon lying ‘behind’ them. The central circle was attractively laid in the basket weave style with a small circular area in the very middle. A notably similar weave was the main feature in a single circle which appeared at West Kennet on 21 June, broken up only by an intriguing central swirl and splay which extended itself as a ghostly path towards the outer edge of the circle – all within the flattened lay.

One more old site for crop circles was visited on 17 June when Cheesefoot Head in Hampshire, once one of the key locations for the phenomenon, received a sharp-looking wheel of 18 triangular ‘blades’, set at an angle like a circular saw disc, encircling a standing crescent at the centre. Followers of mystical traditions, meanwhile, were delighted to see the return to the fields of the Kabbalah, or ‘Tree of Life’, at Badbury Rings in Dorset, on 16 June [pictured under ‘The Value of Free Thinking’ below], a theme which has occurred a number of times since its first appearance in 1997. This year’s version added a few extra sharp-angled paths to its outside, suggesting an evolution of consciousness extending the branches.

The month closed with a very clearly-impressed pictogram in a style more reminiscent of the early 1990s, at East Kennett, Wiltshire, on 26 June. Three circles in a line – one fully flattened, a smaller one with a standing centre and another with a large standing circle within it (or a thick ring if one prefers) – were each beautifully-laid and partly encompassed by thin paths which seemed to hold all of them together in a manner very pleasing to the eye. The full circle was made in a style that is now becoming familiar, in which a band of crop is laid radially in the middle of a conventional swirl [pictured], creating textures that shimmer and look highly effective from the air.

July Astonishments

The ‘cube’ emblem, first seen this year in the Avebury formation of 22 April, returned for its second foray at Lockeridge, Wiltshire, on 1 July, this time encased within a seven-fold flower of standing petals, themselves surrounded by thin rings. A separate small double-ringed circle with a tiny ring at its centre lay nearby. The cube would see its ultimate 2017 expression just a few weeks later.

For decades Warminster in Wiltshire has been the site of an ongoing UFO ‘flap’, and crop circles have peppered its landscape many times. The first of this year’s two stunning entries there, this one near the ancient site of Battlesbury Hill, was discovered on 5 July in the form of a very chunky Celtic Cross [pictured], with each circle ringed and with smaller circles and additional paths within it giving a lovely flowing impression. Very cleanly laid, the effect was breathtaking.

Back at Broad Hinton on 8 July, this time nearer another chalk horse carving at Hackpen Hill (another familiar area for the circles), a stunning six-fold motif of ‘shattered’ triangular elements saw the season move up a gear. Grouped together within six semi-circles in the same style, the artistic intent was at first puzzling to the eye. Looked at more closely, however, the elements resolved themselves into more coherency, revealing the genius behind the layout. Coincidentally or not, unusual rectangular areas of discoloured crop in the field around the formation, made as spray test zones by the farmer, seemed visually appropriate.

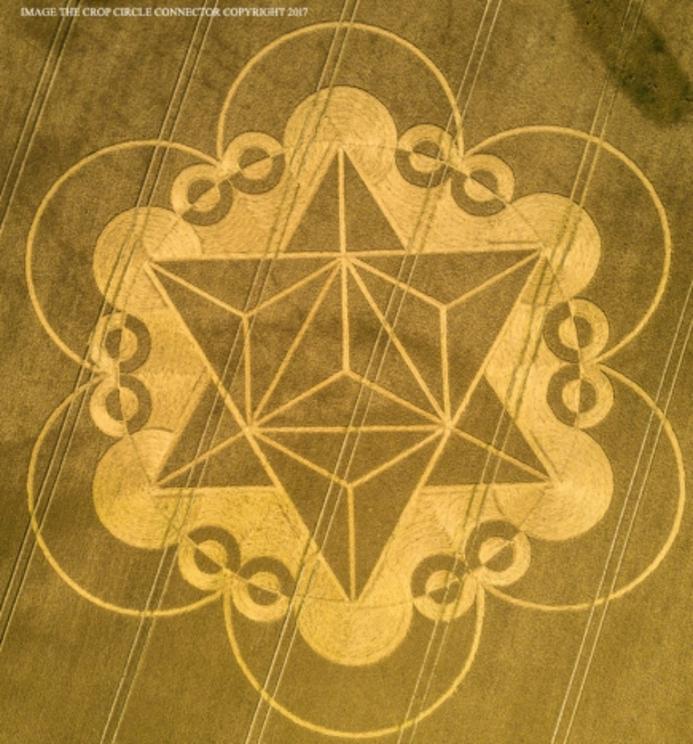

Returning to Warminster, this time beneath the imposing Iron Age hillfort of Cley Hill, what was generally agreed to be the most astonishingly striking design of the summer appeared on 18 July [pictured]. Building on the aforementioned cube theme, the climax to this year’s trilogy was expanded to feature a complex six-pointed star around the cube, seen as if rendered as a three-dimensional geometric model. Surrounding both, a multiplicity of rings and circles, some part laid, part standing, completed the effect to create an exquisitely beautiful and precise achievement on a par with many past masterpieces. The farmer was less impressed, inevitably, but struggled to keep out curious visitors, not helped by the fact that this work of art was clearly visible to anyone driving to or from the nearby stately home and safari park of Longleat. With this arriving just days after the widely-distributed “drone scammers” story, it was clear that such coverage does little to deter human beings drawn to beauty.

Beauty was less of an issue for the last UK event of the month, but it did at least give the county of Bedfordshire a rare circle listing in the form of a crude ring with a central path at Cardington on 21 July. This was notable only for being near the hangar which operated as one of the mooring masts for the ill-fated R101 airship (which crashed in France in 1930). More happily, a new generation of safer British airships are now being developed at the site.

The August Four

The numbers of new events slowed down considerably in August, but the four that occurred, all in England, were worthwhile, beginning with an impressively elaborate twelve-fold flower at Hannington, Wiltshire, on 4 August [pictured]. Comprised of four diminishing bands of curved petals, getting smaller and flatter towards the centre, all encompassed by a ring and four small standing semi-circles, this highly ambitious design was another vote-winner amongst enthusiasts, looking quite wonderful when seen in the landscape.

However, Wiltshire would be deserted in favour of other counties for the last English agriglyphs of the summer. On 5 August, another ancient site saw the arrival of an exquisite mandala near the charming Rollright stone circle at Little Compton in Oxfordshire, host to a number of crop circles in years past. This fascinating endeavour exhibited four five-pointed stars seen as if in stretched perspective, with an unusual octagon at the centre. The main outer edge of the octagon was laid in the basket weave style, with a more conventional swirl and a thin standing ring in the middle.

Wootton Wawen in Warwickshire provided a curious and effective innovation on 7 August [pictured]. At first glance a simple ringed circle with a tiny pointed spur leading to a tail of several small circles, its true qualities could be found in the complicated lay. An offset radially-laid circle with a standing centre was surrounded by a ring, which itself radiated 16 thin paths, like rays, with the crop between them swept straight across. The overall effect was like looking at a bizarre sea creature swimming across the field.

The final UK event occurred at Royston in Essex on 17 August. Site of several formations in the last few years, the main body of this design was a neat standing crescent within a ring, made more peculiar by a grid of radiating lines and symbol-like squiggles which emanated from one side of it. The grid seemed to lack the finesse of the main crescent and was suspected by some to have been added by pranksters afterwards, although there are no photos showing the pattern without it. Thus it was the perfect bamboozling close to another season of stunning, bizarre and sometimes challenging glyphs in the English fields, leaving more questions than answers, as ever.

Global Events

What, then, of the rest of the world, which seems to have fallen so quiet with its circular contributions in recent times? The question of why so much activity is centred around England has never been settled. Occasional years have seen other countries threaten to match or surpass the traditional heartlands in terms of numbers, but the challenge rarely lasts long and the patterns themselves often seem less robust in construction, with a few exceptions. Are we looking at a geological phenomenon at work (the majority of English formations notably cluster around the chalk aquifers) or the selection of one nation to be the centre of something that simply doesn’t need to operate everywhere else to the same degree? Or does the UK simply host the best artists, ethereal or human? We simply don’t know. Yet 2017 did see at least a little global action.

Argentina began the whole season with three thin rings in grass at Carmen de Arceo, near Buenos Aires, on 11 March. The Netherlands began its usual run of slightly odd and sometimes rather scrappy formations (now dismissed as dubious by most researchers) with a single circle at Bosschenhoofd in the Noord-Brabant region on 10 April. Often centred around Hoeven in the same region, and often in grass, some of the designs progressed into other crops as the summer went on, but none were of any great spectacle.

Italy was once a burgeoning area for inventive crop circles, but this year it only managed to produce an elaborate but known man-made art project design made by a team at Scalenghe between 27-28 May, and just one more, of unknown origin, at an unrevealed location on 5 July in the form of thin rings within a triangle and three extending arms of three circles each. Germany, once another hotspot, produced nothing at all this season.

France received two interesting designs in 2017. The first arrived at Crézancy-en-Sancerre in the Cher area on 2 June [pictured] and comprised a neat if slightly bizarre complex of circles bound by thin rings and a crescent at strange angles to each other, rather like a mutated Celtic cross. The second, on 18 June, had an astronomical flavour, featuring a large circle with two thin outer rings, while other rings and circles were superimposed onto them, suggesting some kind of orbital diagram.

Switzerland generated a small but curious design at Delley-Portalban, Fribourg, on 27 June, in the form of a neatly-laid circle with three standing ‘blades’ broken into thin fragments. This was followed by a single circle with a slight bulge on one side at Val-de-Ruz, Neuenburg, sometime in mid-July.

Bulgaria and Poland each produced a single formation in July. The Bulgarian entry, in the Sofia City Province on 5 July, was an attractive six-fold flower with three small circles perched on the edges of three of the very thin petals, rather like a demonstration of atomic physics. Poland’s pattern was somewhat simpler, being a classic double-ringed circle at Bialystok, Woidwodschaft Podlachien, on 29 July.

The later months of the year saw a brief global revival with, on 1 October, an attractive mandala with a central floral motif discovered in grass at Zollikofen, Bern, in Switzerland, while Brazil suddenly received a single ringed circle at Ipuacu, Santa Catarina on 18 October, followed by a thicker ringed circle with four radiating arms of two smaller circles each at nearby Linha Bela Vista on 3rd November [pictured].

… And that was it for documented global activity in 2017: just eleven formations of an unknown variety, plus the usual collection of small Dutch oddities.

A Good Season

For all the apparent slumber of the rest of the world, with 32 English events of mostly ambitious and impressive quality it still feels as if we had a good crop circle season, even though numbers were down on the previous year. Certainly, the National Farmers Union and the police felt moved to act, which is telling.

Some researchers complain that the formations we receive today don’t move them in the same way ones from past years did, but is it just that they have unrealistically raised expectations, anaesthetised by the sheer fantastical quality of the many incredible patterns we have had over the decades and now take too much for granted? Newcomers to the phenomenon continue to be amazed and are drawn into the same journey of wonder that has transformed others before them, which may explain why this very persistent mystery keeps going.

Whilst dramatic innovation may have withdrawn, perhaps since 2002 with the apparent chapter mark of the remarkable ‘alien and disc’ formation and its message, it may be that the crop circles are currently happy to operate at more of a background level right now. No movement can keep going at the same pace forever. It may be that the phenomenon is biding its time, awaiting some new phase in the future. Even so, we really can’t complain.

The reality is that if many of the crop patterns we had in 2017 had appeared back in, say, 1990, the season when the first pictograms exploded into the headlines, they would have been greeted with utter astonishment and a furore, surmounting anything we did actually have in that year, impressive though those pictograms seemed at the time. It is all relative and we should cherish what we have right now, while we have it.

The Value of Free Thinking

In a world where free speech and free thinking is under increasing threat, there is something liberating about this determined and slightly mischievous phenomenon. The crop circles seem to lie outside the normal controls of authority, hence the desperate press releases berating people for being interested in them. Moreover, they inspire (or should) critical thinking and a spirit of enquiry in a way that currently appears to be discouraged by the powers that be, seemingly keener for us to be kept docile and ignorant of anything outside of the narrow channels they define. Anything that bucks this trend should be held dear.

The main achievement of the circles, regardless of their origin, has always been the expansion of consciousness through the journey of open-minded enquiry they inspire. We may need their lessons more than ever in the coming years of increased manipulation, before inevitable cycles turn against suppression to bring more enlightened times where debates are once more opened up rather than closed down. When society re-values and restores free thinking and unrestrained discussion, within wise and reasonable boundaries agreed by all, the world will be a happier place.

Andy Thomas

www.truthagenda.org

Originally written for Nexus Magazine (published there in a truncated form). All photographs courtesy of Crop Circle Connector, for which, many thanks – photos of the whole 2017 season can be found there. Thanks also to Bertold Zugelder for the diagrams taken from www.cropcirclecenter.com, an excellent online archive.