Fairies and the Folklore Society: 1878 -1945

The great Victorian fairy fascination held its grip over culture into the early 20th century. In the wake of the Cottingley photographs, the dark folkloric sprites had seemingly transformed into benign nursery beings. When a group of amateur folklorists, including William Thoms, the father of the term folklore itself, formed the Folklore Society (FLS) in 1878, serious fairy scholarship was born. The FLS members’ writings act as a perfect lens through which the Victorian fairies and their eventual fall from favour can be understood. The fairy as a survival from humankind’s past was seen as a key to unlock the understanding of human culture, ‘primitive’ mindsets and even the prehistoric past. Throughout their works the fairy shape shifts, acting as a mouth piece for various facets of folklore scholarship.

Folklorists collected small fragments of fairy lore still surviving among rural, especially elderly, ‘folk’ in isolated landscapes as an archaeologist might find Neolithic arrowheads or elf bolts. Such snippets of fairy lore were printed in the FLS Journal, generally in the form of unanalysed tales and anecdotes. George Laurence Gomme produced The Handbook of Folklore (1890) which acted as a guiding template for such collectors. It outlined questions to ask and how to categorise the collected data. Fairies were situated in the “Goblindom” category, which included the elfin community, household familiars, ghosts and even enchanted heroes. In conjunction with newly collected material, a series of County Folklore volumes was organised as a society project. Their purpose was to record and categorise less accessible, yet previously printed folklore extracts. However, this proved a little overambitious and the society overreached itself. Only seven volumes were produced between 1892 and 1914. This project’s termination mirrors a trajectory of decline in the society, and indeed, fairies.

A division of labour is also evident between the generally female or regional collector who would record and categorise folklore and the armchair anthropologists, such as Gomme himself, who created grand overarching theories. Charlotte Sophia Burne styled herself as queen of the collectors forging herself a unique place in the society. She rewrote Gomme’s Handbook in 1914, with a more imperial outlook. Gomme’s original category of “Goblindom” becomes subsumed into a wider international pantheon of “superhuman beings” covering all nations. Burne’s handbook is for colonial collectors being more concerned with worship practices, sacrifices, functions, and general religious practice concerning all supernatural beings. Fairies become overwhelmed amongst a plethora of their imperial counterparts. They in effect become diminutive in a key collectors manual.

‘When they were given butterfly wings they were reduced to almost the status of insects, and in the sheltered days of the early twentieth century every care was taken to render them unalarming.’ K. M. Briggs, The Fairies in Tradition and Literature (London, 2002), p. 249.

Fairies also became entangled in the late Victorian folk tale debates, aimed at identifying why global folk tales often appeared to have similar storylines. Andrew Lang, writer and anthropologist, argued for the polygenesis of tales, proposing that similar plots appear in multiple locations due to the similarity of human mindsets and paths of cultural development. However, Joseph Jacobs used his paper ‘The Science of Folk Tales and the Problem of Diffusion’ at the 1891 International Folklore Congress as a platform to attack Lang’s position. Jacobs conversely proposed the theory of monogenesis, that folk tales were created by a single genius and diffused with population migrations, morphing during multiple retellings. On an organisational level the FLS attempted to tabulate folk tale types from around the world according to incidents, hoping to understand their possible origins and distribution patterns. Marian Cox’s Cinderella (1893), with a defensive introduction from Lang, was the first attempt to tabulate the Cinderella tale type. Thus Folklore issues during 1893 and 1894 covered lengthy debates regarding folk tale diffusion. However, very few concrete conclusions were drawn from Cox’s volume. During this era, Edwin Sidney Hartland’s The Science of Fairy Tales (1891) also compared various myths tracing themes such as fairies’ human midwives, changelings, supernatural time lapse in Fairyland and swan maidens. Furthermore, Edward Clodd in Tom Tit Tot (1898) analysed the theme of taboo in knowing a fairy creatures’ name in the Rumpelstiltskin tale type. He unpacked the “savage philosophy” of the tale, including taboos surrounding names and magic through tangible items such as hair and words of power. During the late Victorian era, fairies in folk tales reflect an intense and serious academic debate. Ultimately, as discussions became less polarised, these heated debates died down.

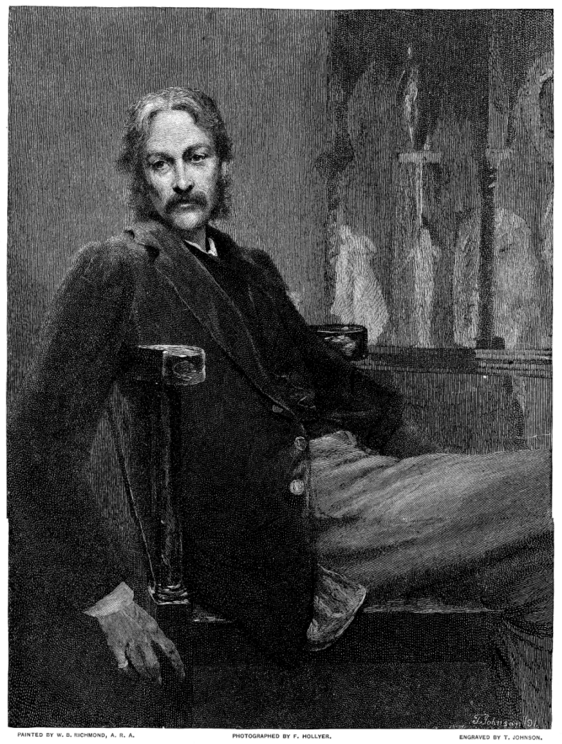

Andrew Lang, editor of the coloured fairy book series, journalist and anthropological folklorist. By T. Johnson Source

Not withstanding these debates, Lang and Jacobs sold numerous children’s folk tale collections. Lang’s coloured fairy books and Jacobs’ English, Celtic, and Indian fairy tales contained some scholarly discussion bridging the audience gap between adult folklore enthusiasts and child readers. Indeed, according to their misguided anthropological theory, such stories represented ‘primitive’ culture from the childhood of mankind; therefore, such stories would naturally appeal to middle-class children. With the advent of the picture book age such volumes firmly situated folk tales and their magical characters in the nursery.

Some FLS members went so far as to claim that fairies represented memories of Britain’s ancient inhabitants, driven into isolated regions by waves of invaders. Gomme, amateur historian and the Society’s “organisation man,” proposed this theory in Ethnology of Folklore (1892). Gomme suggested that fairycraft formed from conquerors’ perceptions regarding the supposed demoniacal powers of indigenous races. Witchcraft, however, represented the descent of original indigenous beliefs. David MacRitchie also advocated this rational theory that fairies represented an indigenous race. In Fairies, Fians and Picts (1893) he looks at various artificial mounds and structures, such as Maes How in Orkney, claiming they represented ‘fairy’ dwellings. Popular memory retained details of this short race but became blurred until the ‘fairies’ shrank into a small supernatural society, transforming the real race into a fantastical one.

‘[T]he population of England was becoming ever more urbanised, people increasingly constructed a dream of Merrie England. This dream-England was bathed in mellow hues: inhabited by contented yokels with picturesque customs, and glorying in a checkered landscape of fields and woods and quiet farms.’ G. Bennett, ‘Folklore Studies and the English Rural Myth’, Rural History 4 (1993), p.78.

Margaret Murray, the controversial witchcraft historian, took this thread of theory into the 20th century. In The Witch-Cult in Western Europe (1921) Murray argued that early modern European witchcraft trials represented the legacy of a Palaeolithic fertility cult, who worshiped a horned god, but whose practices became decadent in the face of Christian persecution. Fairies fit into Murray’s witch cult thesis as an indigenous race driven into marginal areas yet clinging on to, and initiating others into, their ancient religion. Murray’s ideas, although she never acknowledged it, are clearly derived from Gomme and MacRitchie. Her rather monocausal theory fell from academic grace amid criticisms of Murray’s academic practice. Finally, Gerald Gardner, FLS member and founding father of Wicca, included her theory in Witchcraft Today (1954).

Colourful prints in children’s books helped reinforce the cute, miniature fairy in popular culture. Dicky Doyle, ‘In Fairyland’ Source

Fairies were also used to express Celtic nationalism. Alfred Nutt, the main publisher of FLS materials, in The Voyage of Bran (1895-97) discusses the threads of the ‘Happy Other World’ and ‘Doctrine of Rebirth’ through Irish mythology. For Nutt, contemporary fairy lore held by Irish farmers stood as the final strand in this great tradition. Nutt was no Irish nationalist, but rather an admirer of Celtic mythology. His presidential speech ‘The Fairy Mythology of English Literature’ (1897), traced the Celtic strand of fairy lore into Shakespeare’s writings, rather Imperialistically claiming it for England. Likewise, John Rhys, first Professor of Celtic at Oxford and proud Welsh man, brought the Welsh fairies to London. Celtic Folklore, Welsh and Manx (1901) is a compendium of his early writings on Welsh fairy lore. He employs a comparative methodology to link materials he had personally collected to previously recorded Welsh fairy mythology, particularly lake maidens. By packaging his native fairies in a standard folkloric format, Rhys introduced Welsh fairy lore to the English reader.

In the multiple Folk-Lore articles of Irish antiquarian Thomas Westropp, fairies and their related fabled race the Tuatha Dé Dannan are situated amongst the mythology and landscape of County Clare and Connacht. His death in 1922 signalled a major break between the FLS and Irish folklore and fairy lore amid souring Anglo-Irish relations. With the rise of the ‘celtic dawn’ and the works of W.B Yeats, fairies joined the Irish cultural revival, forming an important strand of this new cultural nationalism. Various independent Irish folklore societies, including the Irish Folklore Commission in 1935, were set up during Irish independence. This weakened the FLS’s connection with Irish fairy lore, further damaging fairy scholarship.

‘At last we come to the passing of the fairies. Diligent as ever, in killing the things they loved, the passionate embrace of Victorian love robbed the fairy of breath. A few sad, mummified Victorian fairies survive, pressing in the pages of the Past Times catalogue, perhaps. Some people are devoted to these little corpses, tending them devotedly, but they obstinately refuse to flourish; they have no roots and no branches, no real resonance.’ D. Purkiss, Fairies and Fairy Stories: A History (Stroud, 2007), p. 333.

Finally, by the beginning of the 20th century, fairy iconography in popular culture had become increasingly cute, especially with J.M. Barrie’s character Tinkerbell, Cicely Mary Barker’s flower fairy illustrations, and finally the Cottingley photographs. The triad of children, gardens and fairies which had played out children’s literature in works such as E.S. Nesbit’s Five Children and IT (1902), with its Psammead sand fairy, and Rudyard Kipling’s Puck of Pooks Hill (1906) had seemingly come to fruition. Doyle released the Cottingley photographs in the 1920 Christmas Strand Magazine to international acclaim and controversy. However, despite the obvious interest, the FLS virtually ignored the furore. This was partially because the images looked aesthetically dubious and partially because they claimed to represent actual real fairies rather than surviving ossified historical folklore. In short, Cottingley made fairies look beneath serious folkloric scholarly attention and helped situate fairies firmly in the nursery.

Like the fairies, the FLS itself was in decline. The enthusiastic Victorian founding members with ambitious plans had slowly passed away. Jacobs had moved to America at the turn of the century cooling the debate surrounding folk tales. Nutt died in an accident in 1910; Lang passed away in 1912, and the great organiser Gomme died in 1916. After the war the deaths of Burne in 1923 and Hartland in 1927 ended the tenure of the original members. WW1 also caused disruption for those hoping to conduct research. Some upcoming FLS members also perished in the terrible war. The price of paper rose, making it difficult to print large volumes. Adding to this, Nutt’s company had charitably published many FLS works at a loss; this agreement ended with his premature death. As their publishing power diminished, so did their voice.

‘The fading of the British folklore movement may be viewed as one of the collateral tragedies of the Great War. One can simply scan the sharply reduced volumes of Folk-Lore from 1918 on to see how the lean years followed the fat ones.’ R.M. Dorson, The British Folklorists: A History (London, 1968), p. 44.

This era also hailed a shift in the dominant theoretical landscape of folkloristics. R.R. Marett’s 1918 presidential speech “The Transvaluation of Culture” laid out a template for folklore which included modern phenomena and revivals. Folklore was no longer considered an ossified stratum of ancient surviving culture, but something that could mutate and change. The great debates and ambitious plans of the late Victorian era had ended. As the FLS declined so did the position of the fairies. Only two major articles on fairies appear in Folklore between the wars. MacCulloch’s “Were Fairies an Earlier Race of Men?” and R.U. Sayce’s’ “The Origins and Development of the Belief in Fairies” are multicausal and mainly synthesise Victorian theories. They lack the stronger polemic discussion of late Victorian fairy scholarship.

‘The recognition of their existence will jolt the material twentieth-century mind out of its heavy ruts in the mud, and will make it admit that there is a glamour and mystery to life.’ A.C. Doyle, The Coming of the Fairies (London, 1997), p. 32.

As the twentieth century dawned the fairy slowly become associated with the nursery and childhood. Eventually she was no longer considered a serious adult scholarly pursuit. As the horror of WW1 materialised and the sheer human carnage made man appear as a beast, so our ‘others’ the fairies had to represent a childhood innocence from adult troubles. The shell-shocked generation of the Somme had little room for the merry jests of naughty Robin Goodfellow. The fairy performed a flit, spending most of the twentieth century hiding away in a nursery cupboard, only to re-emerge in a new digital format.

For full references please use source link below