The spiritual shell money of Papua New Guinea

Photographer Claudio Sieber documents how the traditional practice of using shell money continues to thrive among the Tolai people.

Along the shores of the Gazelle Peninsula, in East New Britain, Papua New Guinea, the concept of shelling out money is much more than a turn of phrase. Besides using the national currency, kina, the Tolai people of the region maintain a traditional currency comprised of strings of shells.

Photographer Claudio Sieber spent a month living among the Tolai, documenting shell money’s role in society. With so many people worldwide habituated to paying with plastic, taps, and clicks, Sieber was eager for insights into what the future holds for the currency, known as tabu. He expected to find a cultural relic but instead found a currency that remains vital and relevant. He learned that the governor of East New Britain is planning to establish more shell money banks to give the Tolai additional opportunities for trading or storing their tabu and that entrepreneurs hope to establish a money exchange outlet at the airport in Kokopo, the capital city of East New Britain, which will enable visitors to participate in the shell money economy more readily.

Sieber acquired tabu of his own and set out to see what he could buy: vendors accepted tabu for vegetables, peanuts, tobacco, soda, and mobile phone data. “Sadly, the local car trader refused my idea of buying a new Toyota,” he says. With enough tabu he might have been able to visit an exchange hub and purchase the car with cash instead, as a workaround. “That’s the way many locals cover costly expenses like school or hospital fees.”

While tabu may be used occasionally to buy tangible goods, its real purpose and power is in cultural exchange, says Martin Maden, a Tolai filmmaker from Kokopo. Tabu is sacred currency and a key component of any traditional mortuary ceremony or wedding, in particular. Birthday celebrations, feasts, group initiations, and resolutions of disputes often call for tabu, too.

Maden, now 55, recalls asking his mother to make tabu for him to bring to film school in Paris, France. The Tolai believe that all art is sacred—inspiration for artistic works is transmitted from the spiritual world—so deserves tabu. When he arrived at school, the 21-year-old Maden solemnly placed the stringed shells over the shoulders of his two instructors, honoring them as artists and compensating them for the knowledge they would impart. The act connected the men to Tolai cosmology, and now the spirits of his French elders inspire Maden in his dreams: “They say to me things I never learned in film school, about new ideas, because I did the right thing by the spirits when I was young.”

Here’s a glimpse at a few of the ways that tabu remains entrenched in Tolai society.

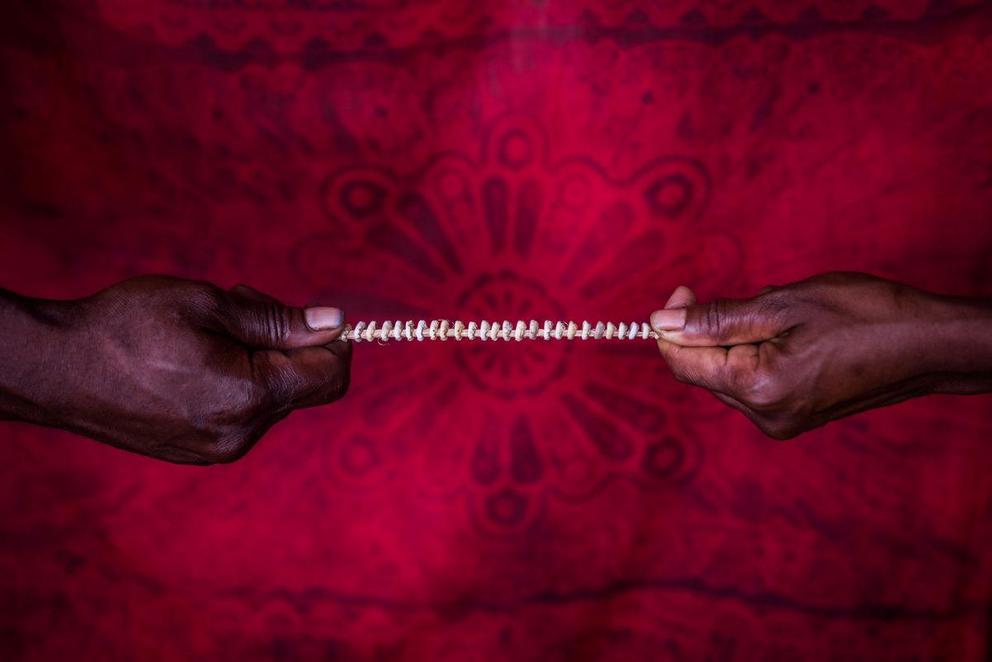

To create tabu, the Tolai use pliers to pinch a hole into the shell of a marine snail known locally as palakanoara, from the family Nassariidae, and then thread it onto rattan cane. The standard unit of tabu currency is one param—a string roughly the length of an adult’s arm span, bearing approximately 300 shells.

Tabu derives its economic value from the effort that goes into producing it and acquires its cultural value as it changes hands over the course of many rituals and ceremonies. Maden explains that new shell money is regarded with suspicion—to make it sacred and drive away any bad magic associated with dead shells, the owner must perform a ritual. The Tolai generally reserve newly fabricated money for ceremonies or traditional payment of large fines. It must feature in at least one mortuary ritual before it can be used as ordinary currency for everyday domestic products.

After many years, when the shells have deteriorated beyond use as currency, they retain their deeper value. “It’s been handled by countless generations of our ancestry, so remains sacred,” says Maden. “So we don’t burn it; we usually bury it under our houses because it has latent energy and power.”

(video can be viewed at the link below)

Transforming snail shells into official currency is a multistep process.

Claudio Sieber

Claudio Sieber

Harvesters typically collect the snails from the mud around mangroves and then dry them in the sun. The shell money economy has stripped East New Britain of its Nassariidae population—now most shells are imported from the Solomon Islands or from other parts of Papua New Guinea. Once tabu has passed through an initial ceremony, the owner may coil large amounts of it into a wheel for storage or banking. The owner carefully marks each wheel with an “account name,” indicating its purpose.

At Shane’s Shop in Kokopo, a customer purchases 10 params (or one arip) of shell money for a celebration. Exchange hubs are new—previously, people would walk around their village to find someone willing to trade. The governor of East New Britain, Nakikus Konga, says that shell money dates back more than 200 years; Maden believes it arose much, much earlier—somewhere between 500 and 1,000 years ago.

A Tolai mortuary ceremony, known as a minamai, includes an appearance by a spiritual being called a tubuan, with a cone head and sphere-shaped body of leaves. Each clan worships its own tubuan, which represents an ancient matriarch. During a minamai, a tubuan visits Earth and delivers the deceased person’s tabu to a public gathering for distribution. Relatives and friends also contribute their own tabu. The act of distribution helps ensure passage for the soul into the “abode of spirits.”

A family member of a deceased man tosses tabu to the crowd during his minamai. Public distribution of shell money typically occurs at mortuary events, though Tolais always look for additional ways to “shake their network” for tabu, Maden says.

Without the distribution of tabu during a mortuary ceremony, the human spirit would be condemned to an afterlife of misery. “Modern money never replaced traditional money because only the tabu can bring you to heaven in our cosmology,” says Maden. Depending on the total amount of tabu distributed, the reputation of the clan of the deceased person increases or decreases.

Attendees of the mortuary ceremony crowd around a vendor after receiving tabu from clan leaders to trade the shell money for buns, ice cream, betel nuts, chips, peanuts, and other goods.

(video can be viewed at the link below)

During a welcome ceremony for tubuans, clan elders pay tribute to the spiritual figures by hurling gifts of shell money at them. The ceremony has significance for interclan networking and reinforcing traditional governance, says Maden.

In Papua New Guinea, a man and his family typically pay a bride price for marriage. “I’ve already paid,” is a common way for a man to explain his relationship status. The bride price ceremony takes place at the bride’s home and compensates her family for the loss of a potential matriarch, Maden explains. The groom’s family must also make payments to the bride’s local government and church community. Tabu is essential for these transactions: “That’s the only thing that makes a marriage sacred in our society,” says Maden. In the ceremony shown here, the groom’s family laid out a mix of kina and tabu totaling around 3,000 kina’s worth (roughly US $920). The 25-year-old bride also received gifts: a bush knife, mattress, blanket, suitcase, buckets, garden rake, and—of course—shell money. “These are emotional, practical, and symbolic gifts of departure from a bride’s clan, wishing her happiness in her new household and reminding her of her responsibilities as the mother of a new clan,” says Maden.

After payment is laid out during a bride price ceremony, the tabu is gathered into a large basket woven from the leaves of a coconut tree for transport. Feasting and dancing soon follow. Maden reports that for a brief period long ago, German seafarers brought shell money made out of plastic in Hamburg to East New Britain’s port, hoping to trade it for coconuts, taro, and other foods. The Tolai accepted it at first, but soon shunned the faux shells.

During the ritual known as kinavai, tubuans dance offshore in a canoe to symbolize the birth of their clan. “A kinavai event can be staged to coincide with modern government or tourism events, but the prime reason that the tubuans are reborn is for the fulfillment of traditional mortuary obligations,” says Maden. A kinavai simultaneously pays tribute to the history of shell money and the seafaring heritage of the clan, he adds. The kinavai depicted here was preceded by men venturing into the jungle at dusk where they played drums, sang, and drank through the night before piling into the canoes as morning broke. From here they will paddle across a harbor to meet a priest arriving by sailboat, to commemorate the arrival of Christian missionaries in the 1800s. After the tubuans dance again, clans will distribute tabu to the crowd.

Tubuans lead the way during a ceremony acknowledging Christianity’s origins in East New Britain before tabu is distributed.

During the photographer’s visit to East New Britain, a small delegation from Japan arrives for the first time to make amends for a three-year Japanese military occupation of the area during the Second World War. The visitors break apart wheels of tabu (with roughly 20,000 shells per wheel) to divvy among the residents, church, and government of East New Britain.

A Japanese priest hands a gift of tabu to a resident near Kokopo. The visitor and his companions also gifted the Tolai a samurai sword as a gesture of peace.

Video can be accessed at source link below.