Fantastic Planet: the visionary body and gnostic evolution

Fantastic Planet is a stunning work of visionary filmmaking, directed in 1973 by Rene Laloux and animated by Roland Topor. It is based on a novel, Oms en série (“Oms Linked Together”), by Stefan Wul. It tells the story of a strange world named “Ygam”, ruled by a race of giant, psychically evolved blue humanoids called the Draag. Humans exist on this world, but they’re known as “Oms” (after the French word “homme” meaning “man”) and are so diminutive compared to the Draags in their size and stature that they are kept as pets. Wild, “un-domesticated” Oms live in tribal societies on the outskirts of Draag settlements and in abandoned places. Draag time passes much more slowly, with one day being the equivalent of 45 Earth days. The trope in this film, used in other popular science fiction at the time like Planet of the Apes (1968), is role reversal: what would happen if we were the vermin on a planet of super evolved sentient life forms?

While the imagery is utterly striking—bizarre creatures dredged up from the depths of the psyche, both beautiful and horrifying, whipping plants and crystalline morning dew—the plot is, by contrast, fairly straight forward. It tells the story of a human boy named Terr (short for “Terror”, but also a play on the word Terra, or Earth) as he is raised as a pet by a Draag family after his mother is cruelly killed by Draag children. Terr is the plaything of Tiwa, the daughter of an important Draag leader Master Sinh.

In a situation like The Matrix, Draags learn by wearing a telepathic device on their heads that imprints the all of knowledge of Draag civilization directly into their memory. Terr accompanies Tiwa during her learning sessions and, somehow, manages to “download” that knowledge, too. When Tiwa becomes bored of her pet, Terr manages to escape to an abandoned park where the wild Oms live, bringing the knowledge of Draag civilization with him. He learns to use this knowledge to their advantage and, without spoiling too much (yet), liberate the Om from their subservient place on Ygam.

VISIONARY BODIES

Before Terr leaves his Draag family, we learn some interesting things about the Draag. They spend most of their time in a state of disembodied meditation. Tiwa’s mother is seen sitting before what looks like an altar. Her signature red eyes fade away as a sphere materializes above the altar and floats up into the sky. Inside the sphere is a mirror-image of her seated in meditation. She joins other Draag as they float like celestial entities across the Ygam sky. While most of plot in Fantastic Planet is the kind of narrative you find in many a classic science fiction story, its the surrealistic imagery of each scene that hypnotizes you. These animations are what modern viewers now have a word for: visionary art. This shouldn’t come as any surprise as the animator, Roland Topor, was a friend of Alejandro Jodorowsky. Jodoworsky enlisted Topor in the 1960s to start a new, psychedelic surrealist movement. If you’ve ever seen Jodo’s films, like El Topo (1970) or Holy Mountain (1973), you know they are visual psychedelics, burned through our retinas in 8mm alchemical fire.

During a disoriented moment as a child, Terr happens upon four seated Draags meditating. Their bodies appear to shapeshift through varied, multicolored forms as their outer skin vanishes, leaving only the nervous system visible in what reminds one of a modern day Alex Grey painting. This is the visionary body of the Draag. They appear to have evolved themselves into a higher-dimensional reality where their physical body is more reminiscent of the astral body in esoteric traditions (such as Anthroposophy and Theosophy). They are more like the denizens of a world described by the religious scholar Henry Corbin: the Mundus Imaginalis, or imaginal world. The entities encountered in these realms of existence are the kind encountered through visionary and psychedelic states.

When the Draag meditate, they project their consciousness—in what might borrow from the Egyptian concept of the “Ba”, or individual soul—into a yet more ethereal body. They float like clouds over the planet, occupied by some form of celestial communion. It is interesting that Topor chose to depict them as spheres, since Plato in the Timaeus postulated that the shape of the soul was a perfect sphere. Carl Jung also linked the image of the soul with the mandala and the archetype of wholeness.

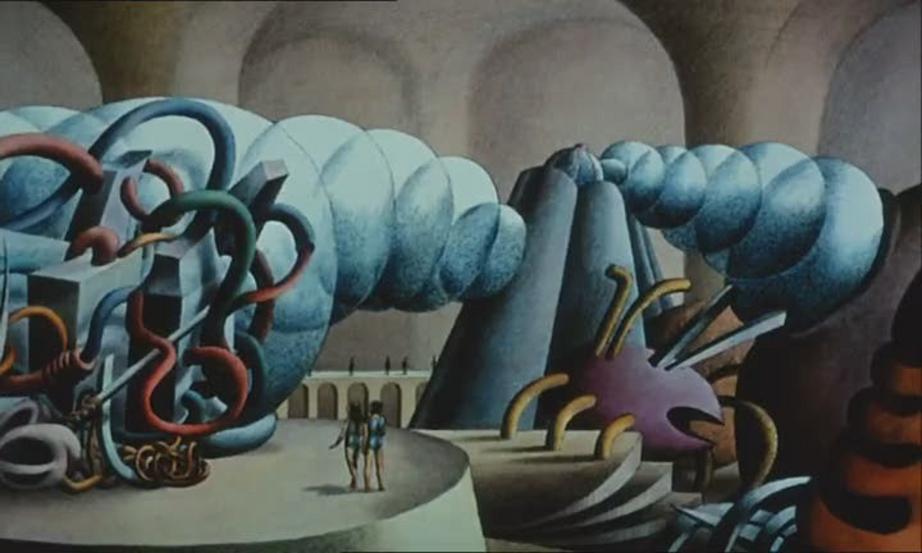

We later learn that this extension of the visionary body is necessary in order for the Draags to procreate. They travel in their disembodied form to their planet’s satellite, called the Fantastic Planet, and participate in a form of imaginal erotic copulation with the consciousness of other alien life forms. Somehow, this helps the Draag mix vital, noetic (meaning ‘of the mind’) traits back to their species and ensure their survival. In short, for the Draag, the only kind of sex is visionary, celestial sex with other beings from the whole universe. Pretty neat stuff.

A VIEW FROM BELOW

All of these wondrous things about the Draag are juxtaposed with the reality that the Om have to endure. Humans are no larger than rodents compared to the Draag, and the film carefully reiterates this in scene after scene by depicting us as ants scurrying about on the ground, desperately attempting to avoid being trampled under foot, flicked around like bugs, or even exterminated with Om pesticide. While the film is certainly having fun with this idea—“how would you like it?”—it also forces us to pause and reflect how we humans treat other sentient beings in our own ecology. The Draag are like us in this respect: wondrous, transcendental, and beautiful in our capacities as we are cruel and aloof to the suffering we inflict on the other occupants of spaceship Earth.

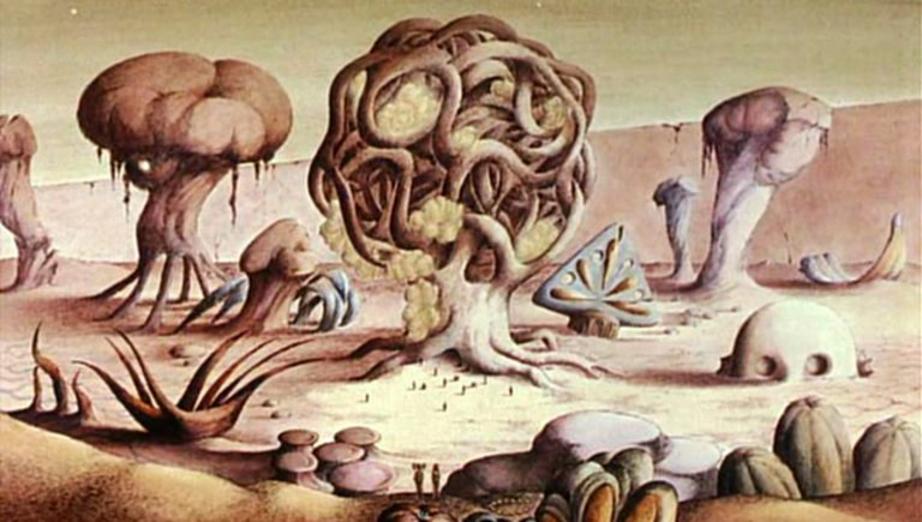

The wild Oms of Ygam are periodically exterminated by the Draag. They clear out humans like we clear out unwanted animal colonies in abandoned areas of the suburbs. One such area is where Terr flees from his Draag masters. There he finds a woman who leads him to an empty Draag park populated with two Om colonies. One is a tribe of bandits that inhabit the stump of a dead tree that, interestingly, resembles a vulva or womb, and the other, slightly more organized society lives inside a huge tree, resembling a mushroom or phallus. What makes this so interesting is that it calls back to an earlier form of human consciousness that philosopher Jean Gebser described as “pre-perspectival”, where the phallic columns of dolmen structures (which are found world-wide) and the prehistoric caves of Chauvet and Lascaux loomed large in our psyche.

In the novel, humanity is taken by the Draag and brought to Ygam as their pets, but in the film, Om origins are left more ambiguous. Humanity may have been a space-faring civilization at one point, but as the Draag research teams noted, we likely destroyed ourselves (another parallel to Planet of the Apes). The Om of Ygam appear to have reverted back to a primordial consciousness of magic and shamanism, performing erotic rituals in the night atop a Draag skull (note the significance of the domed structure, once again, as a space of ritual trance and mystical illumination).

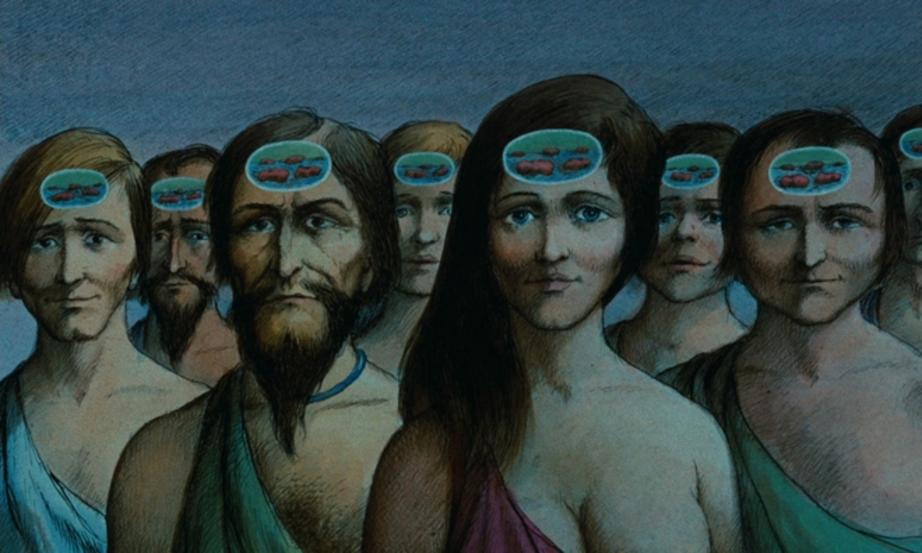

Terr fights for his place Om society, but he isn’t like them. He brings literacy—being able to read Draag writing—and the telepathic headpiece. The Om start tuning into the headpiece in droves. It is interesting to note the imagery of their meditative state the “inner vision”, drawn on their forehead, opening within them. The Om begin to change as they learn about Draag history and technology. They’ve snatched the knowledge of the gods for themselves, and so their consciousness begins to change…

SLAYING DRAAGONS

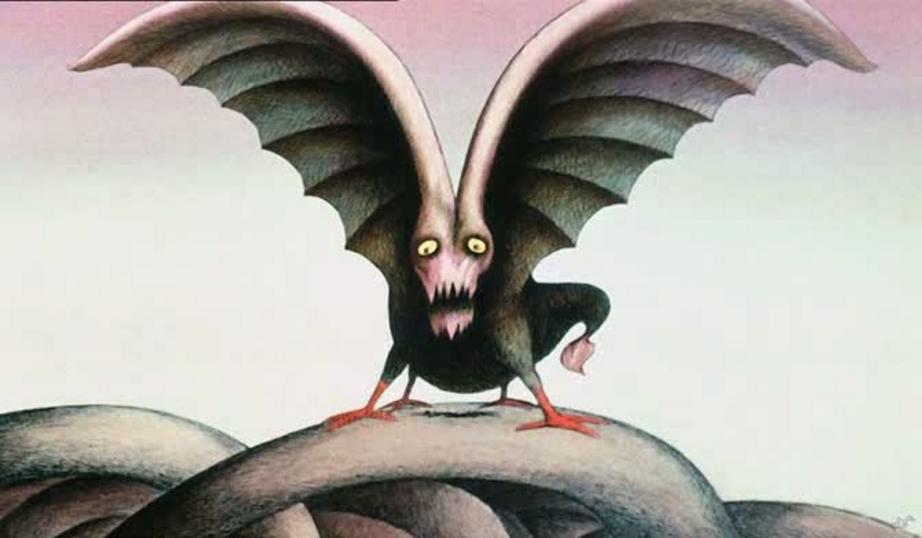

The Oms are confronted by a particularly horrifying beast—a dragon of sorts—that devours some of their tribe like an anteater snatches up ants from a colony. You get the impression this is a monster the Om have encountered before and felt powerless to defend against. But this time something is different. The Om take their new tools and capture the gargantuan beast, killing it. They’ve faced their fears and with a newfound confidence, they’re ready to the Draag.

After noticing that their park has been marked for Om extermination (Terr reads the Draag sign), Terr tries to convince his tribe to leave. They refuse, at first, but when the exterminators come he and the survivors flee deeper into the wilderness.

A number of escaping Om are confronted by two Draags at the border of the park. Instead of turning and fleeing, they use the same tools that took down the flying monster to take down—and kill—one of the Draags. This deeply alarms Draag society and they prepare to exterminate even more of the Om, who are now considered a true threat to their society. Time is running out for the Om.

GNOSTIC MOONSHOT

The Om learn from their headset about the Ygam moon, Fantastic Planet, and decide that it’s probably better than staying on the Draag world, so they hatch a plan to use an abandoned rocket depot and launch themselves there. Hundreds—maybe thousands—of Om assemble at the rocket depot, using the headset to reverse engineer Draag technology and build rockets in the appropriate size for an Om. Terr is the leader of this massive, organized effort, and in many ways he is filling the role of the Moses figure who has heard the voice of the gods and is leading his people, in exodus, to a new world. But this is also a gnostic allegory.

Terr is an Om who has taken knowledge, gnosis, from his demiurgic captors who don’t even recognize his capacity for expanded consciousness. Note the auric quality of the headsets the Draag wear like jeweled crowns on their head. This is reminiscent of the kind of iconography that medieval saints and holy figures were depicted with as halos around their heads, denoting spiritual illumination (and, if you will, the crown chakra). Terr also doesn’t demand authority or power over his fellow Om, but encourages them to partake in gnosis for themselves. And so Terr is a gnostic prophet rather than a mere Biblical one, urging humanity onto the next evolutionary leap. Compared to the vast celestial intelligences and powers in the higher worlds, we are like ants stepping into an infinite and strange imaginal sea. Tremendous beings and archetypal forces await us (recall that some medieval iconographers depicted the spiritual power of holy figures by making them larger than laypeople), but the transformation into a cosmic species is not without great peril.

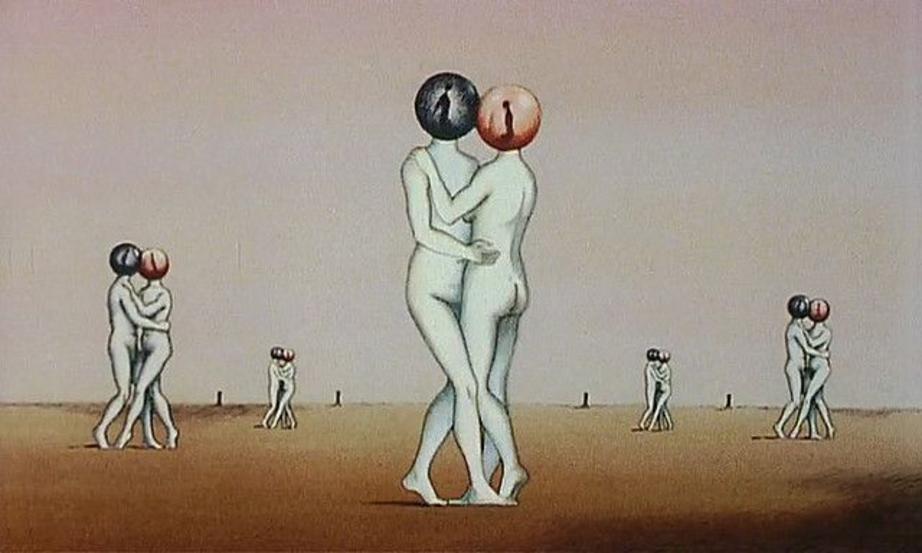

As the exterminators close in on the rocket depot, Terr takes two rockets and blasts off to the Fantastic Planet. There, to his surprise, he finds enormous, headless statues standing in an open plane. These statues become animated by Draag souls—their spherical, projected consciousness—and they proceed copulate with alien souls from other worlds.This is the visionary, celestial sex from earlier. In some kind of theurgic SciFi ritual of statue animation, the Draag bring the statues to life and proceed to copulate with alien souls from other worlds. They dance and sway as the Om look on from their rocket windows, realizing that the Draags use this planet for cosmic copulation. Noetic, rather than DNA, exchange.

Terr starts firing on the Draag statues and they crumble to the ground; the Draag who were meditating in these cosmic tantras collapse back into their bodies, unconscious or perhaps killed. The Draag immediately recall their Om exterminators—realizing that humanity is much more than they ever realized—and peace between the two species is, at last, achieved.

ECOLOGIES OF CONSCIOUSNESS

Fantastic Planet ends rather quickly after this confrontation. We hear from the voice in the computer headset that the Om and the Draag develop a symbiotic relationship with each other. The Om build a new satellite world orbiting Ygam that they call “Terra” after their ancestral home world (Earth). The Om and the Draag are able to share celestial knowledge with one another (perhaps some cosmic copulating was implied), and further the mutual evolution of both species.

The ecological message of the film is prescient. It invokes the gnostic allegory of the fallen humanity who, once again, can reach their celestial station and return to their place in the stars—but here’s the twist: they don’t do it alone. The Draag, as demiurges, end up not being so bad. Ignore, yes, but there is room enough in this corner of the galaxy for two sentient life forms. Fantastic Planet came out only a few years after 2001: A Space Odyssey (1969), the moon landing, and just so happened to be part of a wave of psychedelic, cosmic High Weirdness that made the 1970s so unique. The cultural narratives of humanity moving out of terrestrial and into celestial evolution was all the rage. But in Fantastic Planet, humanity becomes uncanny to itself. We are the “little people” (a description for Faerie folk). We are feral animals staring back at the civilized Draag with ferocious spiritual power. Perhaps this film is about awakening to the net of “interbeing” of all sentient life—in the physical plane and beyond. A plethora of dimensions, endless worlds in the starry firmament. This ocean of lights is both outward and inward, as the Draag remind us, and to leap forward we will need to be ready to embrace the whole ecology of consciousness as we step forth into the Mundus Imaginalis of higher dimensional evolution. Fantastic Planet is a mythology for planetary consciousness, where humanity finds its cosmic voice to participate in the music of the spheres.