What would happen if the Yellowstone super volcano actually erupted?

An aerial flight over Yellowstone’s Midway Geyser Basin in 2004 shows Grand Prismatic Spring and Excelsior Geyser Crater, which drain into the nearby Firehole River.

If the supervolcano underneath Yellowstone National Park ever had another massive eruption, it could spew ash for thousands of miles across the United States, damaging buildings, smothering crops, and shutting down power plants. It'd be a huge disaster.

A SUPER-ERUPTION WOULD BE HORRIFIC — THOUGH ALSO PRETTY UNLIKELY

But that doesn't mean we should all start freaking out. The odds of that happening are thankfully pretty low. The Yellowstone supervolcano — thousands of times more powerful than a regular volcano — has only had three truly enormous eruptions in history. One occurred 2.1 million years ago, one 1.3 million years ago, and one 664,000 years ago.

And despite what you sometimes hear in the press, there's no indication that we're due for another "super-eruption" anytime soon. In fact, it's even possible that Yellowstone might never have an eruption that large again.

Even so, the Yellowstone supervolcano remains an endless source of apocalyptic fascination — and it's not hard to see why. In September 2014, a team of scientists published a paper in Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems exploring what a Yellowstone super-eruption might actually look like.

Among other things, they found the volcano was capable of burying states like Wyoming, Montana, Idaho, and Colorado in three feet of harmful volcanic ash — a mix of splintered rock and glass — and blanket the Midwest. That much ash could kill plants and animals, crush roofs, and short all sorts of electrical equipment:

Ash, ash, everywhere

When I called up one of the study's co-authors, Jacob Lowenstern of the US Geological Survey, he stressed that the paper was not any sort of prediction of the future. "Even if Yellowstone did erupt again, you probably wouldn't get that worst-case scenario," he says. "What's much, much more common are small eruptions — that's a point that often gets ignored in the press." (And even those small eruptions are very rare.)

Lowenstern is the Scientist-In-Charge of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory in Menlo Park, California. So I talked to him further about what we actually know about the Yellowstone supervolcano, what its eruptions might look like, and why the odds of disaster are low.

What is the Yellowstone supervolcano?

Lurking beneath Yellowstone National Park is a reservoir of hot magma five miles deep, fed by a gigantic plume of molten rock welling up from hundreds of miles below. That heat is responsible for many of the park's famous geysers and hot springs. And as magma rises up into the chamber and cools, the ground above periodically rises and falls.

THE VAST, VAST MAJORITY OF YELLOWSTONE ERUPTIONS ARE SMALL

On rare occasions throughout history, that magma chamber has erupted. The vast, vast majority of those eruptions in Yellowstone have been smaller lava flows — with the last occurring at Pitchstone Plateau some 70,000 years ago.

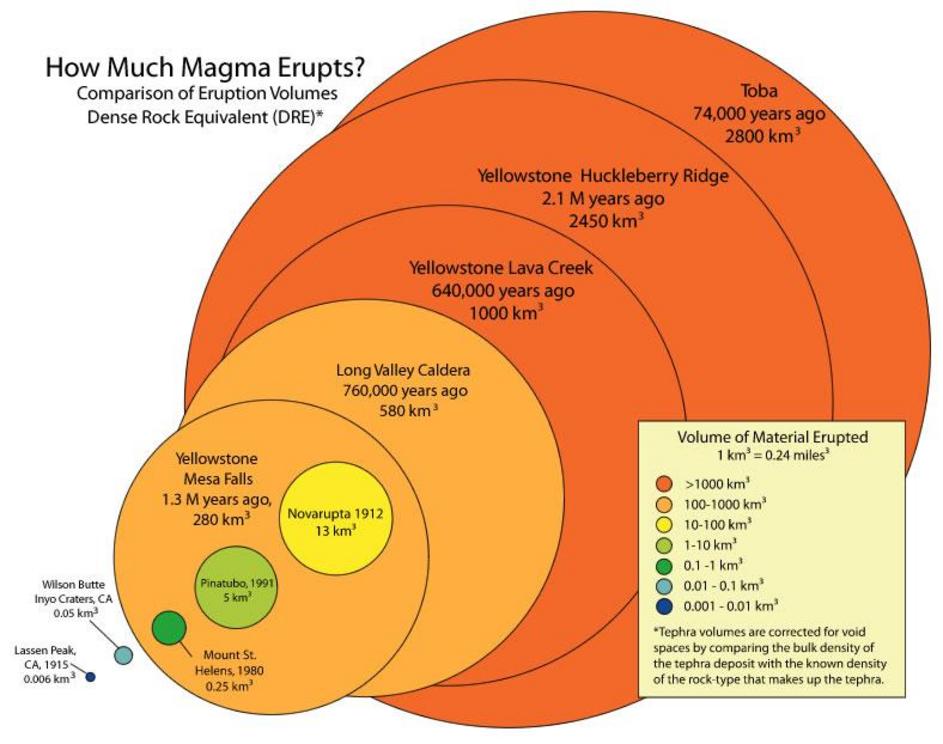

But the reason why Yellowstone gets so much attention is the remote possibility of catastrophic "super-eruptions." A super-eruption is anything that measures magnitude 8 or more on the Volcano Explosivity Index, in which at least 1,000 cubic kilometers (or 240 cubic miles) of material gets ejected. That's enough to bury Texas five feet deep.

These super-eruptions are thousands of times more powerful than even the biggest eruptions we're used to. Here's a chart from USGS comparing the Yellowstone super-eruptions with the Mt. St. Helens eruption of 1980. The difference is staggering:

Super-eruptions vs ordinary eruptions

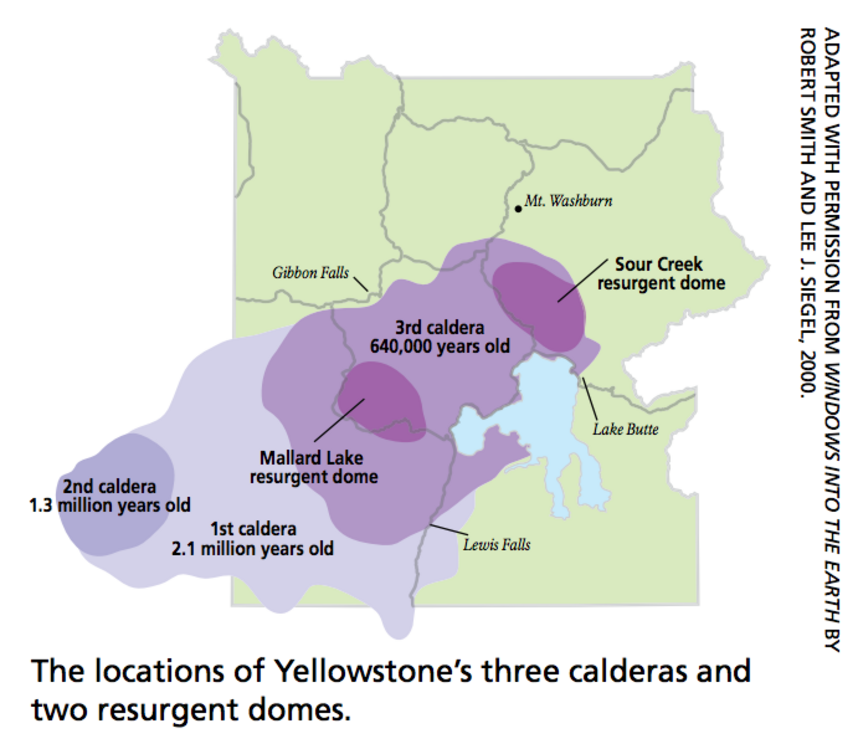

Yellowstone has had three of these really massive eruptions in its history — 2.1 million years ago, 1.3 million years ago, and 664,000 years ago. The last of those, at Yellowstone Lava Creek, ejected so much material from below that it left a 34-mile-by-50-mile depression in the ground — what we see today as the Yellowstone Caldera:

Location of past Yellowstone super-eruptions

It's worth noting that Yellowstone is hardly the only supervolcano out there — geologists have found evidence of at least 47 super-eruptions in Earth's history. The most recent occurred in New Zealand's Lake Taupo some 26,000 years ago.

More dramatically, there was the gargantuan Toba eruption 74,000 years ago, caused by shifting tectonic plates. That triggered a dramatic 6- to 10-year global winter and (according to some) may have nearly wiped out the nascent human race.

On average, the Earth has seen roughly one super-eruption every 100,000 years, although that's not an ironclad law.

So what would a Yellowstone eruption look like?

Let's reiterate that the odds of any sort of Yellowstone eruption, big or small, are very low. But if we're speaking hypothetically…

The most likely eruption scenario in Yellowstone is a smaller event that produced lava flows (similar to what's happening at Iceland's Bárðarbunga right now) and possible a typical volcanic explosion. This would likely be precipitated by a swarm of earthquakes in a specific region of the park as the magma made its way to the surface.

A SUPER-ERUPTION IS CAPABLE OF SENDING ASH MANY THOUSANDS OF MILES

Now, in the unlikely event of a much bigger super-eruption, the warning signs would be much bigger. "We'd likely first see intense seismic activity across the entire park," Lowenstern says. It could take weeks or months for those earthquakes to break up the rocks above the magma before an eruption.

And what if we did get a super-eruption — an event that was 1,000 times more powerful than a regular volcanic eruption, ejected at least 240 cubic miles of material, and lasted weeks or months? The lava flows themselves would be contained within a relatively small radius within the park — say, 40 miles or so. In fact, only about one-third of the material would actually make it up into the atmosphere.

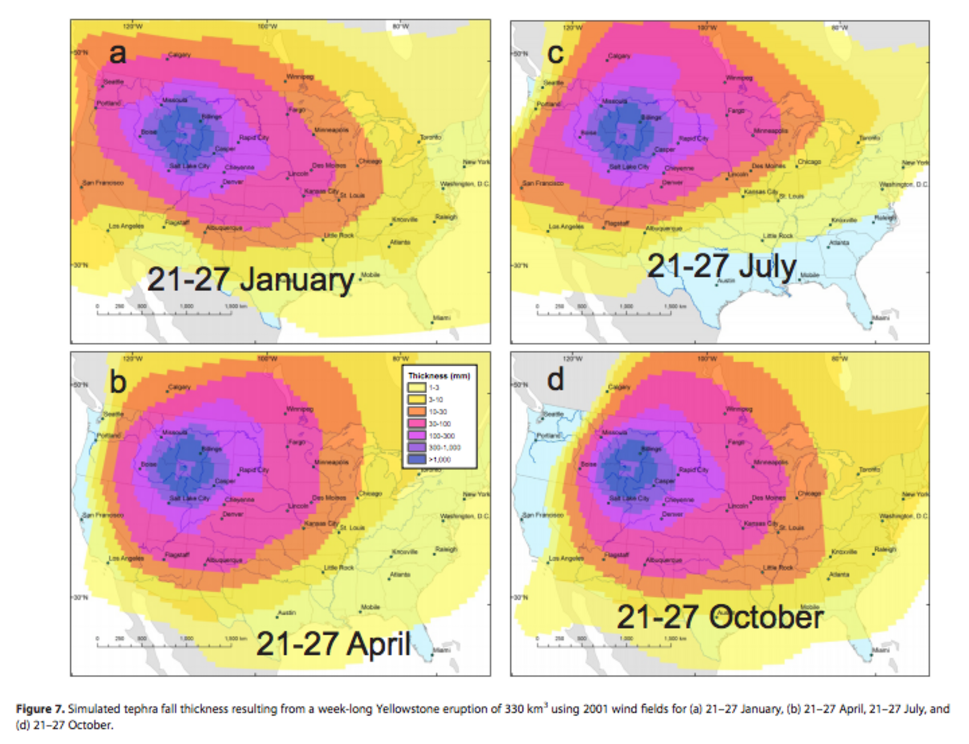

The main damage would come from volcanic ash — a combination of splintered rock and glass — that was ejected miles into the air and scattered around the country. In their new paper, Lowenstern and his colleagues looked at both historical ash deposits and advanced modeling to conclude that an eruption would create an umbrella cloud, expanding even in all directions. (This was actually a surprising finding.)

A super-eruption could conceivably bury the northern Rockies in three feet of ash — devastating large swaths of Wyoming, Idaho, Colorado, Montana, and Utah. Meanwhile, the Midwest would get a few inches of ash, while both coasts would see even smaller amounts. The exact distribution would depend on the time of year and weather patterns:

Modeling the spread of ash from a Yellowstone super-eruption

Any of those scenarios would be terrible news. That much volcanic ash is capable of killing people, plants, and animals and crushing buildings. Even a few inches of ash (which is what much of the country can get) can destroy farms, clog roadways, cause serious respiratory problems, block sewer lines, and even short out transformers. Air travel would have to shut down across much of North America.

AN ERUPTION THAT BIG WOULD ALSO COOL THE PLANET TEMPORARILY

A volcanic eruption that big would also have major effects on the global climate. Volcanoes can emit sulfur aerosols that reflect sunlight back into the atmosphere cool the climate. These particles are short-lived in the atmosphere, so the effect is only temporary, but it can still be dramatic.

When Pinatubo erupted in 1991, it cooled the planet by about 1°C (1.8°F) for a few years. The Tambora eruption in 1815 cooled the planet enough to damage crops around the world — possibly leading to famines in some areas. And those were relatively tiny eruptions compared to what a supervolcano is, in theory, capable of.

Yikes! So what are the odds of a Yellowstone super-eruption?

Very, very low. In fact, it's even possible Yellowstone might never erupt again.

'ODDS ARE VERY HIGH THAT YELLOWSTONE WILL BE ERUPTION-FREE FOR THE COMING CENTURIES'

Right now, there's no sign of a pending eruption. Yellowstone park does continue to get earthquakes, and the ground continues to rise and fall, but that's nothing out of the ordinary. "Yellowstone is behaving as it has for the past 140 years," the USGS points out. "Odds are very high that Yellowstone will be eruption-free for the coming centuries."

The USGS also notes that, if you simply took the past three eruptions, the odds of Yellowstone erupting in any given year are 0.00014 percent — lower than the odds of getting hit by a civilization-destroying asteroid. But even that's not a good estimate, since it's not at all certain that Yellowstone erupts on a regular cycle or that it's "overdue" for another eruption. In fact, there might never be a big eruption in Yellowstone again.

"The Earth will see super-eruptions in the future, but will they come in Yellowstone? That's not a sure thing," says Lowenstern. "Yellowstone's already lived a good long life. It may not even see a fourth eruption."

Volcanoes, after all, do die out. The magma chamber below Yellowstone is being affected by two opposing forces — the heat welling up from below and the relative cold from the surface. If less heat comes in from below, then the chamber could conceivably freeze, eventually turning into a solid granite body.

It's also worth noting that the volcanic hotspot underneath Yellowstone is slowly migrating to the northeast (or, more accurately, the North American tectonic plate above the hotspot is migrating southwest). You can see the migration below:

The volcanic hotspot is sloooooowly moving northeast

On a long enough time scale, the hotspot will move out from under Yellowstone — and the Yellowstone supervolcano would, presumably, die out. Of course, it's possible that another supervolcano could emerge further in the northeast, but the hotspot would first have to heat up and melt the cold crust first. And that process could take a million years or longer.

"It's hard to get our minds around something like a million years," Lowenstern says. "Humans are a relatively brand-new species. But Earth's been around a very long time, and these systems take a long time to do what they do."

For the rest of this article please go to source link below.