What is the end of an age? Understanding the precession of the equinoxes

From New Dawn Special Issue Vol 15 No 6 (Dec 2021)

Timing is everything. Everything moves in cycles. Our days are defined by the turning of the earth, our weeks and months by the cycle of the moon, while the seasons of the year are caused by the relationship between the earth and the sun.

The monthly cycle of a woman’s body, upon which the conception and birth of every child depends, has been associated with the cycle of the moon from ancient times. Despite a condescending denial of this ancient association in recent decades by proponents of “modern science” – who argue that there is no way heavenly bodies such as the moon impact biological functions in women or men – recently published findings from a long-term study over fifteen years revealed that the moon does indeed impact that monthly cycle (see “Women temporarily synchronize their menstrual cycles with the luminance and gravimetric cycles of the Moon,” Science Advances, January 2021, www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abe1358).

For the past twelve years, I have been exploring and presenting evidence that the world’s ancient myths are based on the stars and heavenly cycles – that ancient stories and all the characters and figures described in them correspond directly to constellations and celestial features. This is an esoteric system stretching around the globe and forming the foundation for myths from every inhabited continent and island, including the myths of the cultures of the Americas, Africa, Australia, the islands of the Pacific, as well as ancient India, China, Mesopotamia, Egypt, Japan, and Greece. This system forms the foundation for the Norse myths and for the stories contained in the scriptures of the Bible, from Genesis all the way to the Revelation of John.

The myths use the heavenly cycles, including the cycles of the moon and the planets, but most especially the annual cycle with its effect on the hours of darkness and light as we move through the equinoxes and solstices. They are part of an esoteric language in which different parts of the cycle are understood to represent specific aspects of our experience in this incarnate life and thus convey powerful truths for our understanding and benefit.

In addition to the cycles with which we are familiar from our own experience, such as the annual cycle with its changing seasons and lengths of the day, the ancient myths also use the less obvious and far more gradual cycle known as precession. This is a cycle unfamiliar to most people and rarely taught in formal schooling or mentioned in anything we see on television or in the movies. It proceeds at such a slow pace that even an entire human lifetime of carefully observing the heavens will barely reveal its subtle action.

Indeed, the motion of precession is so subtle and gradual that it was not even articulated by any writers of whose work we are today aware, until the work of the astronomer Hipparchus who lived between the years we today designate as 190 to 120 BCE. Many centuries passed before astronomers could narrow down estimates of the rate of the motion of precession with any degree of accuracy.

Understanding Precession

To understand why precession is so difficult to detect, let’s examine its effect on what we see in the sky from our vantage point on earth. If we spend any amount of time looking at the stars at night, we will soon observe that the position of the constellations slowly changes as we go throughout the year.

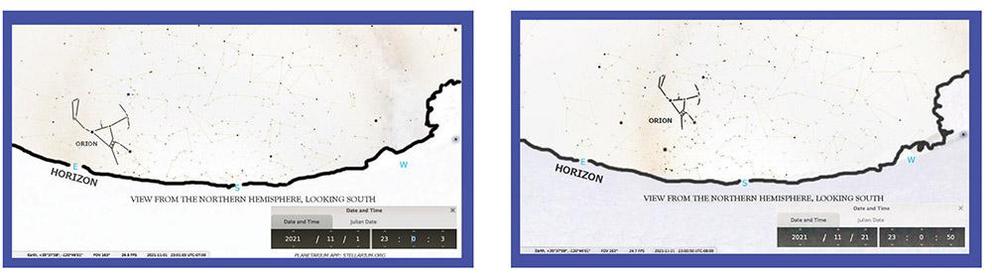

FIGURE 1 (left): Date and time box show that at one hour before midnight, on 1st November, all the stars of Orion have now risen in the east and are above the horizon. FIGURE 2 (right): As we move through the year, the stars rise a few minutes earlier each night. Thus, they are farther along their journey from the east to the west at the same time on successive nights. Here we see that by the 21st of November, the stars of Orion have moved much higher by the same hour shown above: one hour before midnight.

For example, as I write this at the very end of October and beginning of November, the majestic constellation we call Orion is rising above the eastern horizon in the hours after dark, such that the entire constellation clears the hills to the east of where I live about one hour before midnight (see Figure 1). However, as we continue through the year, the stars of the constellation Orion will rise just a little bit earlier each night (about four minutes earlier per night, at the latitude where I live), such that in just a few weeks the entire form of Orion will be above the eastern horizon two hours before midnight, and thus even higher in the sky later on (see Figure 2). In a few months, the constellation will be high in the sky nearing its zenith.

This change in the position of the constellations as we go from one night to another is a result of the changing relationship between the earth and the sun as we move through the year. Orion dominates the night sky during November through April (the winter months for the northern hemisphere), but as the year goes on and the stars of Orion continue rising earlier and earlier each night, the constellation will be farther and farther along its journey from east to west as the sun goes down, until at last we will observe that at nightfall, when the stars start to become visible, the familiar form of Orion is all the way over at the western horizon. As the year progresses even further, into the end of May and the beginning of June, Orion will already be below the western horizon when night falls and the stars appear.

Because this movement is a function of our annual dance with the sun, the position of any given star (say, for example, the centre star in Orion’s famous three-star belt) will be back in its same position when we on earth get back to the same point relative to the sun in our annual cycle. Of course, to measure this phenomenon precisely, we need to stand in exactly the same spot from one year to the next. In fact, we have to rest our chin (or our telescope) in exactly the same location. If we do, we should find that the star in question is in its expected position when we get back to the exact same point in our annual cycle.

How do we know when we get back to the exact same point in our annual cycle? We cannot simply use an ordinary calendar and pick the exact same calendar date (such as November 1st) and assume that we are back to the same point relative to the sun. As we know, the calendar “slips” around a little bit from one year to the next due to the fact that our earth’s daily turning does not match up evenly with our annual cycle. The earth turns on its axis 365 times and a little bit more each year, which means that we have to come up with corrections such as the concept of the “leap year” to keep the calendar from slipping to the point that January 1st falls in the summertime instead of the wintertime (for the northern hemisphere) due to that little extra bit of turning each year.

So, if we want to know when we are back to the exact same point in our relationship with the sun, it is much easier to observe the great station points of the year that we call the solstices and the equinoxes. If we use the winter solstice, for example, to measure some specific star, we will know we have returned to the exact same point in our annual cycle. We can see if that star is in the same place that it was the prior winter solstice (keeping in mind that we will need to take our measurement at the exact same time and with our chin or our telescope in the exact same place as when we measured that star’s location the year before).

If we are very careful with our measurements, then we should find that the same star is in its appointed place the following year. That is what we, in fact, do find because when we get back to the exact same point in relation to the sun, we should be able to look up into the sky at exactly midnight (for example) and trust that the scene in the heavens is the same it was when we crossed midnight at this exact same point in the annual cycle the year before.

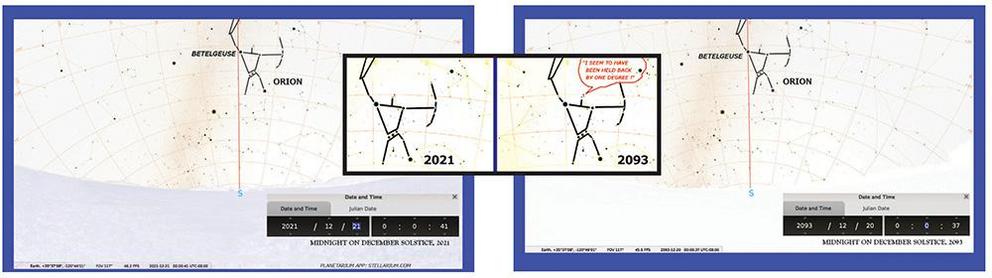

FIGURE 3 (left): Position of the stars of Orion midnight on December solstice, 2021. Compare this to the position of the same stars 72 years later, shown in Figure 4: the “delaying” action of precession will “hold the stars back” ever so slightly after 72 years, but only by a single degree of arc. FIGURE 4 (right): Position of the stars of Orion midnight on December solstice, 2093. The gears of precession grind very slowly, but after 72 years, the stars have been “held back” by one degree of arc. Observe, for example, the position of the star Betelgeuse, at Orion’s shoulder just below the upraised arm: it has ben “delayed” by about one degree over 72 years on the December solstice.

But there is another motion going on which throws a twist into the orderly round of the march of the stars from one year to the next. It is so subtle that we will not be able to measure it very easily with standard equipment unless we take the same measurements every year for a very long time. Over the course of many years, the expected star will keep returning to its expected spot on the expected day, but if we measure its position each year for many decades (keeping careful records each year, of course), we will begin to see it “struggling” to make it to its appointed spot in the heavens – as if some force is very slowly “delaying” that star or “holding it back” from one year to the next.

This action is so slow and subtle that it takes 72 years for that star to be held back by a single degree of arc (about the width of your littlest finger, held at arm’s length from your face). Due to that very slow delay, after 72 years the star will be delayed by a whole degree on the appointed day and time from the place that you measured it at the exact same place and time, 72 years before. Indeed, this delay holds back all of the stars. It is as if the entire fabric of the heavens is held back ever so slightly over decades so that Orion is one degree lower 72 years from now on the night of (let’s say) the December solstice than Orion will be this year on the December solstice at the same hour – and so will the stars of Taurus, and the Pleiades, and all the rest of them.

Of course, very few astronomers can make 72 successive annual measurements of the same star as we’ve just described, even if they start at the early age of 10 years old. For the ancients to even perceive the motion of precession would require meticulous record-keeping for more than one human lifetime – not to mention a system for ensuring that all the observers rested their chins in precisely the same spot when taking annual measurements.

Even after 72 years of observation, the delay is very slight – just one degree! And for the stars to be delayed by two degrees would take another 72 years, or a total of 144 years to get the two-degree displacement. After thousands of years, this “delaying action” will have a real impact.

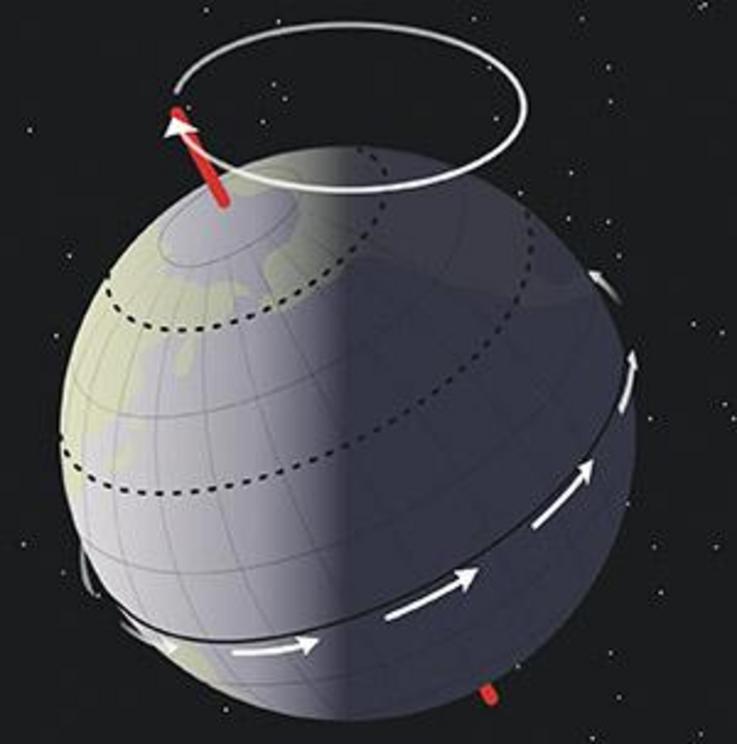

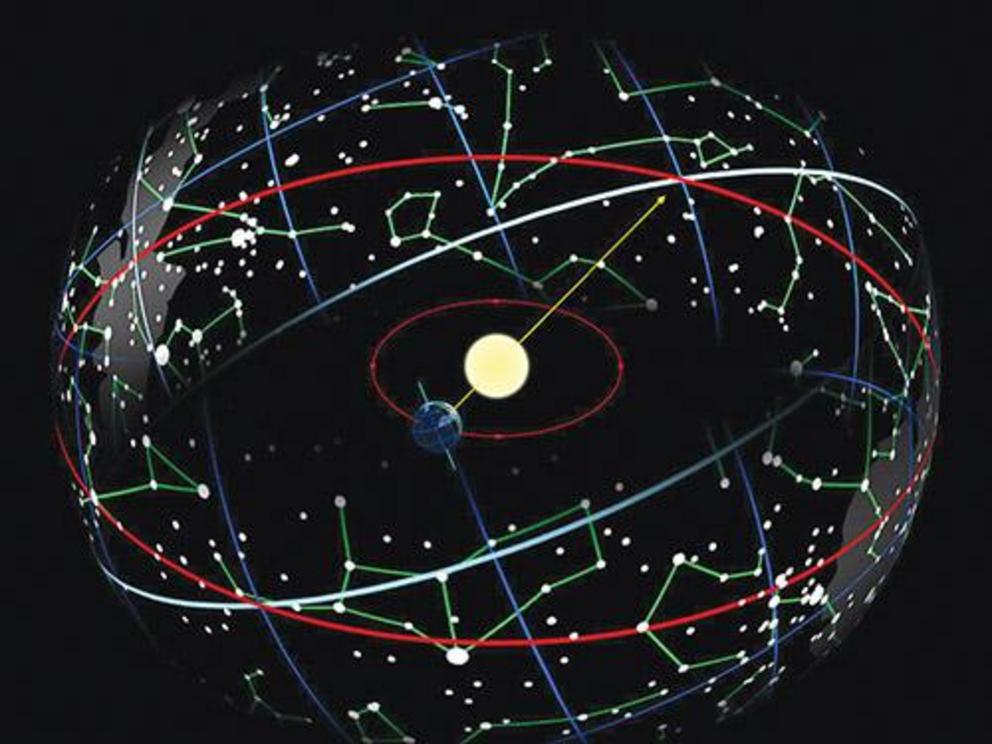

FIGURE 5: Precession appears to “hold back” the night sky by one degree every 72 years due to a 23.5° wobble of Earth’s axis as shown here. One cycle of the wobble takes approximately 25,920 years, which is 12 x 2,160 years.

The reason this motion is called “The Precession of the Equinoxes” is that, after thousands of years, this slight delaying action changes the background of stars such that the constellation expected above the horizon before sunrise on the significant morning of the March equinox (the spring equinox for the northern hemisphere) will be delayed so much that it will still be below the horizon – and the constellation that normally precedes it in the march across the sky and through the year will be above the horizon instead.

We know there are 360 degrees in a complete circle, so if the motion of precession delays the background of stars by one degree every 72 years, we can determine how many years it takes to delay the constellation expected to be just ahead of the sun on the morning of the March equinox (or even the constellation in which the sun is located on the March equinox, although we obviously can’t see the stars once the sun clears the horizon) due to the action of precession.

FIGURE 6: Another way of seeing the action of precession. Earth in its orbit around the sun causes the sun to appear on the celestial sphere moving along the ecliptic (red), which is tilted 23.5° with respect to the celestial equator (blue-white). Over very large spans of time, different zodiac constellations appear behind the sun as it rises at the March equinox. Image credit: Wikipedia/Tau’olunga

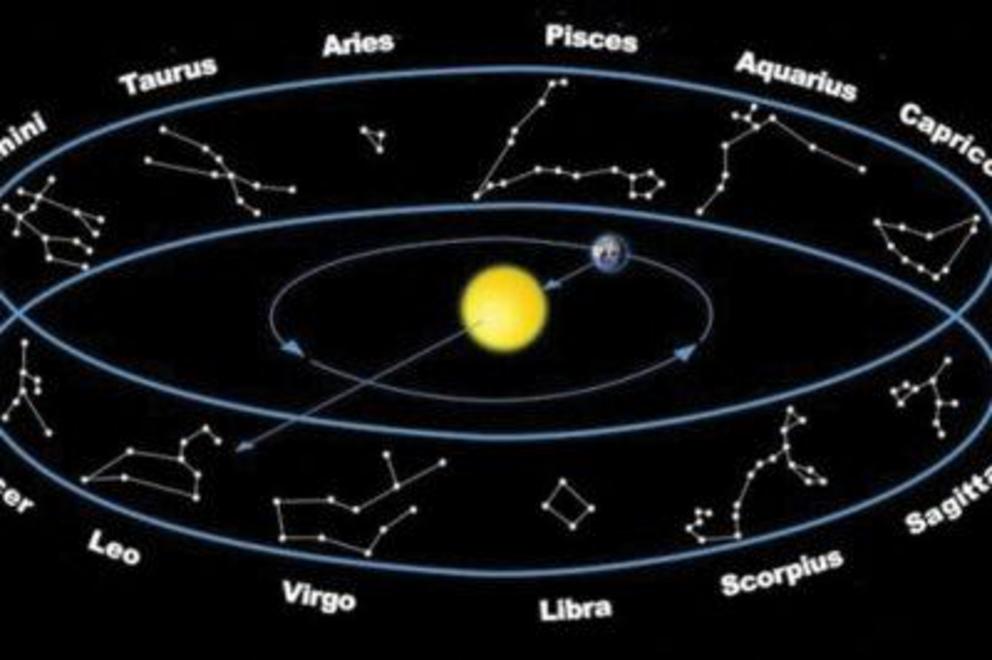

The constellations along the plane of our solar system, the plane between the earth and sun, is known as the “ecliptic.” The background constellations along this ecliptic plane are known as the zodiac constellations. Although the constellations are not all exactly the same size, if there are 12 zodiac constellations and 360 degrees in a full circle, then we can calculate that each constellation in the zodiac should occupy a space of that circle totalling 30 degrees (since 360 degrees in a circle, divided by 12 zodiac constellations, gives us 30 degrees per zodiac constellation). Thus, if precession “holds back” the night sky by one degree every 72 years, then it would take 2,160 years for this motion of precession to delay the sky so much that the expected zodiac sign above the eastern horizon on the morning of the March equinox is “held down” completely below the horizon, such that the preceding zodiac constellation would be above the horizon instead.

The same is true for the zodiac constellation forming the background for the sun itself on the March equinox – after 2,160 years of delaying action, the sun will be in the “preceding” constellation instead of the “expected” constellation. In other words, the sun will have “precessed” into the preceding constellation of the zodiac due to the inexorable motion of precession.

Understanding the End of an Age

This replacement of one entire zodiac constellation by another is what is meant by the “End of an Age.” An “Age” is a precessional Age and is generally identified with the constellation in which the sun rises on the March equinox during that entire Age. The Age of Taurus eventually gave way (due to the delaying motion of precession) to the Age of Aries (Aries being the zodiac constellation that precedes Taurus across the sky), and after another 2,160 years or so, the Age of Aries in turn gave way to the Age of Pisces, which is now giving way to the Age of Aquarius.

The authors of the seminal 1969 book Hamlet’s Mill, Professors Giorgio de Santillana and Hertha Von Dechend, made the brilliant observation that this subtle motion of one constellation taking over the special position in the sky from a preceding constellation could be allegorised in myth. For example, in the usurpation of the throne of the rightful ruler by a jealous brother, as in the story of Osiris and his usurping brother Set, in the mythology of ancient Egypt.

They went on to observe that all “End of the World” imagery common in myths (not only in the Bible where we find the apocalyptic scenes described in the Revelation of John and some of the sermons of Jesus in the gospels, but also in other myth-systems such as the Norse myths with their prophesies of Ragnarokk), must be allegorisations of the “End of a Precessional Age.” One “world” is (figuratively speaking) destroyed and replaced with a new one. The heavenly arrangement of the Age of Taurus, for example, was replaced by the arrangement of the Age of Aries, in which the sun rose in the new sign on the March equinox and also in the new sign on the other important stations of the annual cycle, including the June solstice, September equinox and December solstice.

To support their argument, the authors of Hamlet’s Mill found “precessional numbers” relating to the cycle operating in myths around the globe, particularly in myths having to do with these themes of “usurpation” and the “End of the World.” For example, they point out that the ancient philosopher Plutarch tells us quite specifically that in the myths of ancient Egypt, the rightful king Osiris is killed by his jealous brother Set along with seventy-two henchmen!

It should be noted that the actual rate of precession is not one degree every seventy-two years exactly, but rather one degree every 71.6 years – but we should be able to understand why the myths “round up” to 72 for a metaphorical story.

Similarly, as the authors of Hamlet’s Mill also note, the Norse myths tell us (in the Poetic Edda also known as the Elder Edda) that when the final dreadful day of Ragnarokk arrives, the heroes of Odin’s hall of Valhalla will march out to do battle. The verses declare that Valhalla has 540 doors, through each of which will march eight hundred warriors on the day and that they must go to battle with the Wolf on the last day, for a total of 432,000 warriors (which, of course, relates to the precessional number of 72 and to the 2,160 years of a precessional Age, in that 432 is double 216 and six times 72).

These numbers constitute a powerful argument in favour of their theory. Moreover, in the intervening years since Hamlet’s Mill was published, I found abundant evidence to support their theory in that the imagery in these apocalyptic battles and cataclysms (whether we are talking about the scenes described in the Book of Revelation or in the descriptions of Ragnarokk, or in other apocalyptic battles from other mythologies, such as the great Battle of Kurukshetra in the Mahabharata of ancient India) can be shown to correspond to specific constellations – proving beyond any doubt that these “End of the World” scenes are celestial metaphor.

What is the purpose of such metaphor? That can be debated, although it stands to reason that if the cycle of the moon has an impact on the time of month that a woman can conceive a new life, then the other cycles up to the slow and inexorable turning of the cycle of precession can have an impact on our lives.

I am also quite convinced that the myths use these heavenly cycles as an esoteric code to convey to us powerful messages about subjects we should understand in this life. The “displacing” motion of precession (by which one constellation’s place is “usurped” by another) relates to themes of displacement in our own life, including the theme of alienation, which I have found to be a central theme in the myths – alienation, indeed, from our own Self, which some pioneering modern psychologists connect to psychological trauma. The myths appear to have a dominant central theme about alienation from our Self and the path towards recovery. A subject that should interest all of us, very deeply.

For an introduction to the ancient system of understanding the stars, read David Warner Mathisen’s Star Myths of the World Volumes One through Four, available from all good bookstores. His most-recently published books are The Ancient World-Wide System (2019) and Myth and Trauma (2020). Book previews are available at www.starmythworld.com.

This article was published in New Dawn Special Issue Vol 15 No 6.

For full references please use source link below.