What if a 'perfect CME' hit Earth?

You've heard of a "perfect storm." But what about a perfect solar storm? A new study just published in the research journal Space Weather considers what might happen if a worst-case coronal mass ejection (CME) hit Earth. Spoiler alert: You might need a backup generator.

For years, researchers have been wondering, what's the worst the sun could do? In 2014, Bruce Tsurutani (JPL) and Gurbax Lakhina (Indian Institute of Geomagnetism) introduced the "Perfect CME." It would be fast, leaving the sun around 3,000 km/s, and aimed directly at Earth. Moreover, it would follow another CME, which would clear the path in front of it, allowing the storm cloud to hit Earth with maximum force.

Above: a SOHO image of a coronal mass ejection (CME). MORE

None of this is fantasy. The Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) has observed CMEs leaving the sun at speeds up to 3,000 km/s. And there are many documented cases of one CME clearing the way for another. Perfect CMEs are real.

Using relatively simple calculations, Tsurutani and Lakhina showed that a Perfect CME would reach Earth in only 12 hours, allowing emergency managers little time to prepare, and slam into our magnetosphere at 45 times the local speed of sound. In response to such a shock, there would be a geomagnetic storm perhaps twice as strong as the Carrington Event of 1859. Power grids, GPS and other high-tech services could experience significant outages.

Sounds bad? Turns out it could be worse.

In 2020, a team of researchers led by physicist Dan Welling of the University of Texas at Arlington took a fresh look at Tsurutani and Lakhina's Perfect CME. Space weather modeling has come a long way in the intervening 6 years, so they were able to come to new conclusions.

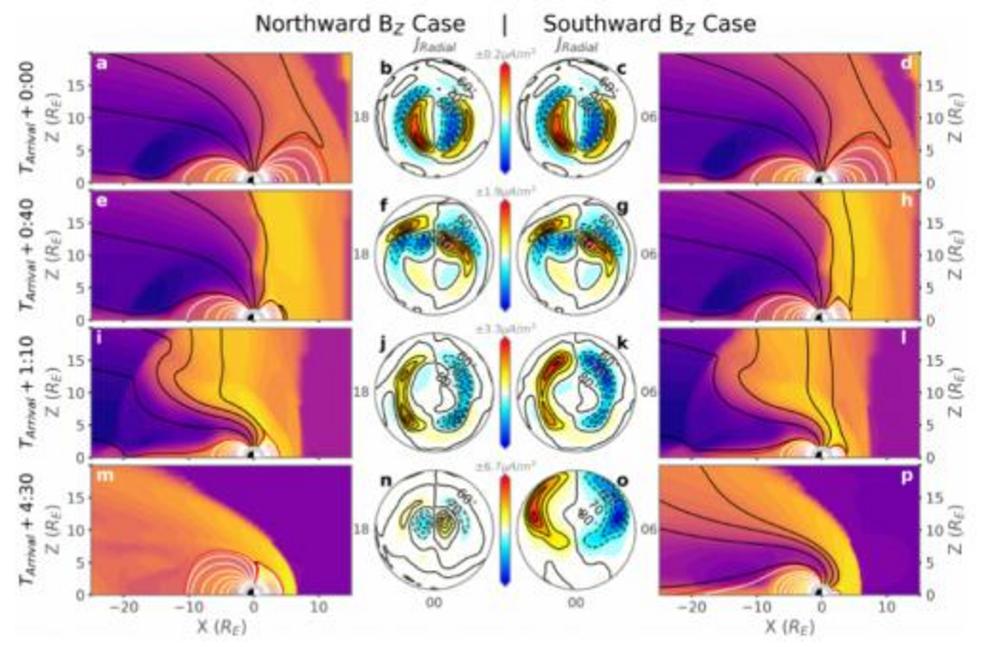

Above: Sample results from computer modeling a Perfect CME impact. The images show the distortion and compression of Earth’s magnetic field as well as induced currents in the atmosphere. Source: Welling et al, 2020. FULL CAPTION

"We used a coupled magnetohydrodynamic(MHD)-ring current-ionosphere computer model," says Welling. "MHD results contain far more complexity and better reflect the real-world system."

The team found that geomagnetic disturbances in response to a Perfect CME could be 10 times stronger than Tsurutani and Lakhina calculated, especially at latitudes above 45 to 50 degrees. "[Our results] exceed values observed during many past extreme events, including the March 1989 storm that brought down the Hydro-Quebec power grid in eastern Canada; the May 1921 railroad storm; and the Carrington Event itself," says Welling.

A key result of the new study is how the CME would distort and compress Earth's magnetosphere. The strike would push the magnetopause down until it is only 2 Earth-radii above our planet's surface. Satellites in Earth orbit would suddenly find themselves exposed to a hail of energetic charged particles, potentially short-circuiting sensitive electronics. A "superfountain" of oxygen ions rising up from the top of Earth's atmosphere might literally drag satellites down, hastening their demise.

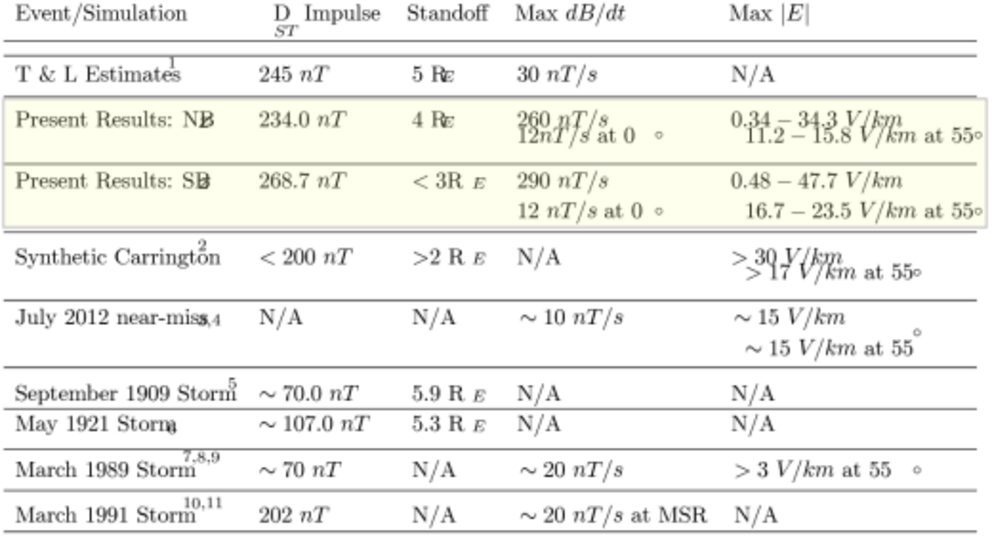

For specialists, Table 1 from Welling et al's paper compares their simulation of a Perfect CME impact (highlighted in yellow) to past extreme events:

You don't have to understand all the numbers to get the gist of it. A Perfect CME strike would dwarf many previous storms.

Now for the good news: Perfect CMEs are rare.

Angelos Vourlidas of Johns Hopkins University has extensively studied the statistics of CMEs. He notes that SOHO has captured only two CMEs with velocities greater than 3,000 km/s since the start of operations in 1996. "This means we expect roughly one CME ejected at speeds above 3000 km/s per solar cycle," he says. Speed isn't the only factor, however. To be "perfect," a 3000 km/s CME would need to follow another CME, clearing its path, and both CMEs must be aimed directly at Earth.

It all adds up to something that doesn't happen every day. But one day, it will happen. As Welling et al conclude in their paper, "Further exploring and preparing for such extreme activity is important to mitigate space-weather related catastrophes."