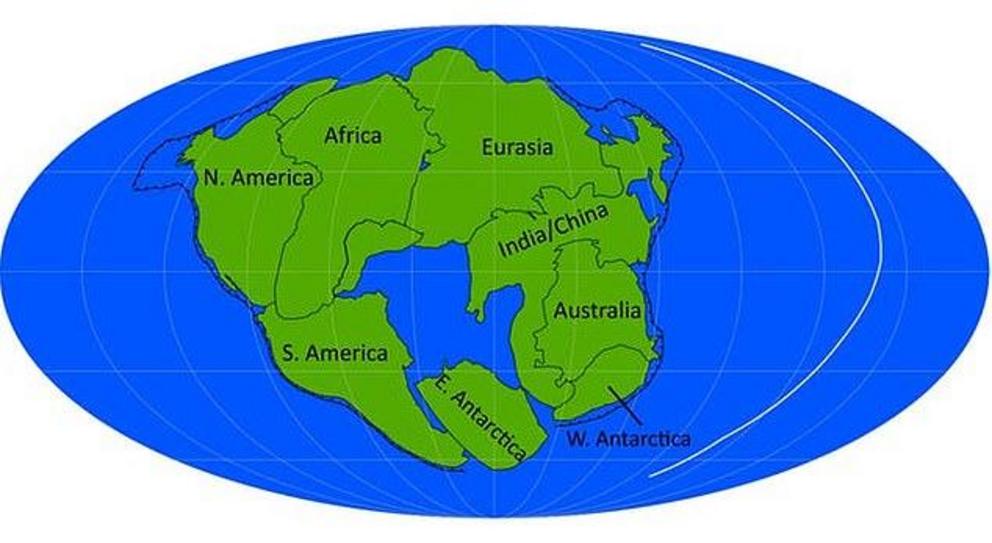

What Earth might look like in 200 million years

The outer layer of the Earth, the solid crust we walk on, is made up of broken pieces, much like the shell of a broken egg.

These pieces, the tectonic plates, move around the planet at speeds of a few centimetres per year.

Every so often they come together and combine into a supercontinent, which remains for a few hundred million years before breaking up.

Researchers say the next supercontinent will form in 200-250m years. The most likely is Novopangea, pictured, where the Americas collide with the Antarctica, and into the already collided Africa-Eurasia.

HOW DO SUPERCONTINENTS FORM?

Earth's tectonic plates, move around the planet at speeds of a few centimetres per year.

Every so often they come together and combine into a supercontinent, which remains for a few hundred million years before breaking up.

The plates then disperse or scatter and move away from each other, until they eventually – after another 400-600 million years – come back together again.

The plates then disperse or scatter and move away from each other, until they eventually – after another 400-600 million years – come back together again.

The last supercontinent, Pangea, formed around 310 million years ago, and started breaking up around 180 million years ago.

It has been suggested that the next supercontinent will form in 200-250 million years, so we are currently about halfway through the scattered phase of the current supercontinent cycle. The question is: how will the next supercontinent form, and why?

There are four fundamental scenarios for the formation of the next supercontinent: Novopangea, Pangea Ultima, Aurica and Amasia.

How each forms depends on different scenarios but ultimately are linked to how Pangea separated, and how the world's continents are still moving today.

The breakup of Pangea led to the formation of the Atlantic ocean, which is still opening and getting wider today.

Consequently, the Pacific ocean is closing and getting narrower.

The Pacific is home to a ring of subduction zones along its edges (the 'ring of fire'), where ocean floor is brought down, or subducted, under continental plates and into the Earth's interior.

There, the old ocean floor is recycled and can go into volcanic plumes.

The Atlantic, by contrast, has a large ocean ridge producing new ocean plate, but is only home to two subduction zones: the Lesser Antilles Arc in the Caribbean and the Scotia Arc between South America and Antarctica.

EARTH'S NEW SUPERCONTINENT: HOW IT COULD LOOK

1. Novopangea

If we assume that present day conditions persist, so that the Atlantic continues to open and the Pacific keeps closing, we have a scenario where the next supercontinent forms in the antipodes of Pangea.

The Americas would collide with the northward drifting Antarctica, and then into the already collided Africa-Eurasia.

The supercontinent that would then form has been named Novopangea, or Novopangaea.

Of the four scenarios researchers believe that Novopangea is the most likely

2. Pangea Ultima

The Atlantic opening may, however, slow down and actually start closing in the future.

The two small arcs of subduction in the Atlantic could potentially spread all along the east coasts of the Americas, leading to a reforming of Pangea as the Americas, Europe and Africa are brought back together into a supercontinent called Pangea Ultima.

This new supercontinent would be surrounded by a super Pacific Ocean.

Subduction in the Atlantic could potentially spread all along the east coasts of the Americas, leading to a reforming of Pangea

3. Aurica

However, if the Atlantic was to develop new subduction zones – something that may already be happening – both the Pacific and Atlantic oceans may be fated to close. This means that a a new ocean basin would have to form to replace them.

In this scenario the Pan-Asian rift currently cutting through Asia from west of India up to the Arctic opens to form the new ocean.

The result is the formation of the supercontinent Aurica.

Because of Australia's current northwards drift it would be at the centre of the new continent as East Asia and the Americas close the Pacific from either side.

The European and African plates would then rejoin the Americas as the Atlantic closes.

(video can be accessed at source link below)

4. Amasia

The fourth scenario predicts a completely different fate for future Earth.

Several of the tectonic plates are currently moving north, including both Africa and Australia.

This drift is believed to be driven by anomalies left by Pangea, deep in the Earth's interior, in the part called the mantle.

Because of this northern drift, one can envisage a scenario where the continents, except Antarctica, keep drifting north.

This means that they would eventually gather around the North Pole in a supercontinent called Amasia.

In this scenario, both the Atlantic and the Pacific would mostly remain open.

Amasia is a scenario where the continents, except Antarctica, keep drifting north

Of these four scenarios we believe that Novopangea is the most likely.

It is a logical progression of present day continental plate drift directions, while the other three assume that another process comes into play.

There would need to be new Atlantic subduction zones for Aurica, the reversal of the Atlantic opening for Pangea Ultima, or anomalies in the Earth's interior left by Pangea for Amasia.

Investigating the Earth's tectonic future forces us to push the boundaries of our knowledge, and to think about the processes that shape our planet over long time scales.

It also leads us to think about the Earth system as a whole, and raises a series of other questions – what will the climate of the next supercontinent be? How will the ocean circulation adjust? How will life evolve and adapt?

These are the kind of questions that push the boundaries of science further because they push the boundaries of our imagination.