These bacteria digest toxic metals and poop out tiny gold nuggets

Handy.

No other life form on our planet has infiltrated every environment as successfully as the minuscule single cells of bacteria. Amongst their many roles in life on Earth, it turns out some of these microbes are also experts at purifying precious metals.

An international team of researchers has figured out how one metal-gobbling bacterium, Cupriavidus metallidurans, manages to ingest toxic metallic compounds and still thrive, producing tiny gold nuggets as a side-effect.

Just like many other elements, gold can move through what's known as a biogeochemical cycle - being dissolved, shifted around, and eventually re-concentrated in Earth's sediment.

Microbes are involved in every step of this process, which has led scientists to wonder how they don't get poisoned by the highly toxic compounds that gold ions usually form in the soil.

The rod-shaped C. metallidurans was first found to poop gold nuggets back in 2009, when scientists discovered that it somehow manages to ingest toxic gold compounds and convert them into the element's metallic form without any apparent danger to the organism itself.

"The results of this study point to their involvement in the active detoxification of gold complexes leading to formation of gold biominerals," lead researcher, geomicrobiologist Frank Reith said in 2009.

Now, after years of investigation, Reith and his colleagues finally know the precise mechanism of how the bacterium achieves this amazing feat.

C. metallidurans thrives in soils which contain both hydrogen and a range of toxic heavy metals. This means the bacterium doesn't have much competition from other organisms that can be easily poisoned in such an environment.

"If an organism chooses to survive here, it has to find a way to protect itself from these toxic substances," says co-author of the latest study, microbiologist Dietrich H. Nies from Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg in Germany.

As it turns out, the bacterium has a pretty ingenious protective mechanism, which involves not just gold, but also copper.

Compounds containing both of these elements can easily get into C. metallidurans cells. Once inside, they interact in such a way that copper ions and gold complexes get transported deep inside the bacterium, where they could potentially wreak havoc.

To deal with this problem, bacteria employ enzymes to shift the offending metals out of their cells - for copper, there's an enzyme called CupA. But the presence of gold causes a new problem.

"When gold compounds are also present, the enzyme is suppressed and the toxic copper and gold compounds remain inside the cell," says Nies.

At this point other bacteria might just give up and go live somewhere less toxic, but not C. metallidurans. This organism has another enzyme up its sleeve, which scientists have labelled CopA.

With this molecule, the bacterium can convert the copper and gold compounds into forms that are less easily absorbed by the cell.

"This assures that fewer copper and gold compounds enter the cellular interior," explains Nies.

"The bacterium is poisoned less and the enzyme that pumps out the copper can dispose of the excess copper unimpeded."

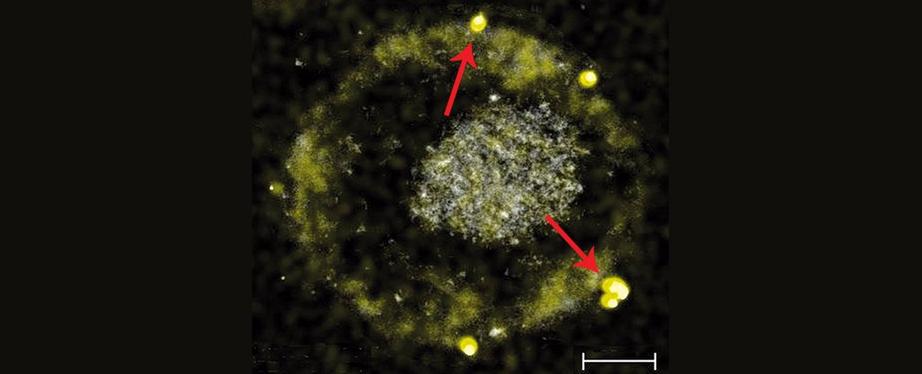

But not only does this process let the microbe shed all that unwanted copper, it also results in teeny tiny gold nugget nanoparticles on the bacterial surface.

The results of this research, which builds on previous work by the same team, are a fascinating insight into the workings of a strange microbe. But on top of that, the bacterium's weird talent could actually be put to a good use.

Understanding how C. metallidurans can poop out gold nuggets means scientists just got a huge step closer to unlocking the biogeochemical cycle of gold.

In the future these insights could be used to refine the precious metal from ores that only contain small amounts of metal - something that's currently a very tricky prospect.

The research has been published in Metallomics.