The sun is spitting out strange patterns of gamma rays

—and no one knows why

The discovery, although mysterious, might provide a new window into the depths of our most familiar star

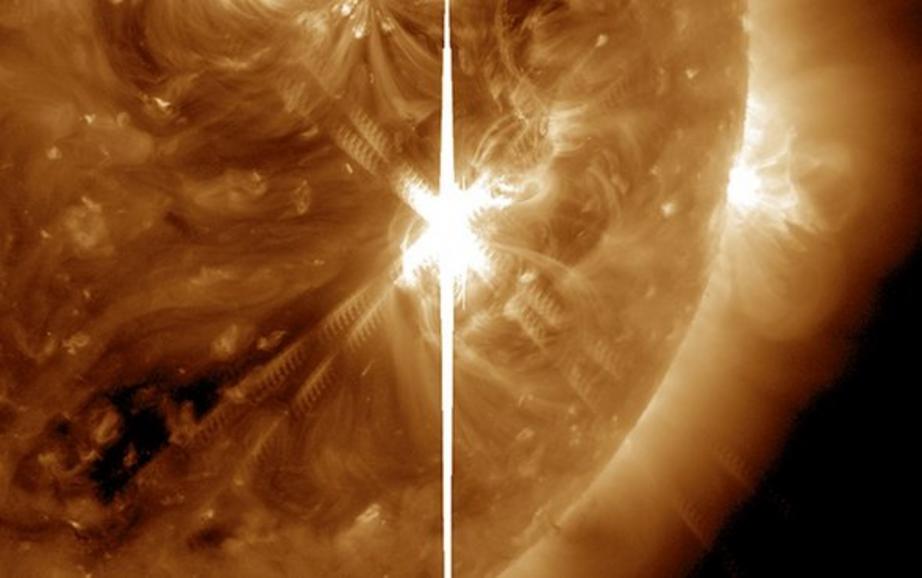

The sun belches out a powerful solar flare and coronal mass ejection (CME) in this image taken by NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory on September 6, 2017. New analysis of data from NASA’s Fermi space telescope suggests that the sun’s emission of gamma rays—the most energetic electromagnetic radiation in the universe—may be linked with CMEs and other outbursts, which follow a roughly 11-year cycle of activity. Credit: NASA, SDO

Our closest star remains an enigma. Every 11 years or so its activity crescendos, creating flares and coronal mass ejections—the plasma-spewing eruptions that shower Earth with charged particles and beautiful auroral displays—but then it decrescendos. The so-called solar maximum fades toward solar minimum, and the sun’s surface grows eerily quiet.

Scientists have studied this ebb and flow for centuries, but only began understanding its effects on our planet at the dawn of the space age in the mid-20th century. Now it is clear that around solar maximum the sun is more likely to bombard Earth with charged particles that damage satellites and power grids. The solar cycle also plays a minor role in climate, as variations in irradiance can cause slight changes in average sea-surface temperatures and precipitation patterns. Thus, a better understanding of the cycle’s physical drivers is important for sustainable living on Earth.

Yet scientists still lack a model that perfectly predicts the cycle’s key details, such as the exact duration and strength of each phase. “I think the solar cycle is so stable and clear that there is something fundamental that we are missing,” says Ofer Cohen, a solar physicist at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. One obstacle to figuring it out, he says, is that crucial details of the apparent mechanisms behind the cycle—such as the sun’s magnetic field—are largely hidden from our view. But that might be about to change.

Tim Linden, an astronomer at The Ohio State University, and his colleagues recently mapped how the sun’s high-energy glow dances across its face over time. They found a potential link between these high-energy emissions, the sun’s fluctuating magnetic field and the timing of the solar cycle. This, many experts argue, could open a new window into the inner workings of our nearest, most familiar star.

In their upcoming study, so far published on the preprint server arXiv and submitted to Physical Review Letters, Linden and his colleagues examined a decade’s worth of data from NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope to better analyze the sun’s emission of gamma rays—the universe’s most energetic form of electromagnetic radiation. To their surprise, the researchers found the most intense gamma rays appear strangely synced with the quietest part of the solar cycle. During the last solar minimum, from 2008 to 2009, Fermi detected eight high-energy gamma rays (each with energies greater than 100 giga–electron volts, or GeV) emitted by the sun. But over the next eight years, as solar activity built to a peak and then regressed back toward quiescence, the sun emitted no high-energy gamma rays at all. The chances of that occurring at random, Linden says, are extremely low. Most likely the gamma rays are triggered by some aspect of the sun’s activity cycle, but the details remain unclear.

For the rest of this article please go to source link below.