The Fermi Paradox, the Martian Conundrum, and a flaw in Dark Forest theory

Isaac Asimov and Robert Heinlein. Arthur C. Clarke and Frank Herbert. Philip K. Dick, who died in poverty, but whose stories have become Hollywood blockbusters. They are giants of the genre, of the Golden Age of Science Fiction (Herbert and Dick don’t officially qualify for the time frame, but they are giants nonetheless). All of them dreamed big, their flights of grand-scale imagination showing us futures where mankind might spread across the galaxy and beyond. They shared their dreams with us, changed our society and our mindsets, and inspired generations of scientists and engineers who later gave us the greatest achievements of NASA and of CERN.

But not one of these, the best and brightest of the genre, seem to have ever addressed a particular problem presented by H. G. Wells, who is sometimes referred to as a “father of science fiction”.

We’ll get to that problem in a moment. First, bear in mind just how important, how utterly crucial science fiction has been to humanity. Many of the most important devices we have today were first described in science fiction, from cell phones to self-driving cars, from submarines to rockets, from earbuds to atomic power. Arthur C. Clarke was the first to describe communications satellites, and in the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey (based on Clarke’s novel of the same name), there’s a few scenes including something that looks (and functions) suspiciously like an iPad:

Suffice it to say that science fiction has vastly changed our world, mostly for the better, and so we should take seriously the important questions posed by sci-fi authors…and by scientists. One particular scientist, Enrico Fermi, of Manhattan Project fame (or infamy), asked in so many words, “So where is everybody?” That’s the essence of the Fermi Paradox. As old as Earth, our solar system, the galaxy, and the universe as a whole is, surely we should be able to detect radio waves (or other forms of communications) from other civilizations, right? Maybe not.

Dark Forest Theory

Such are the great benefits and possibilities of science fiction, but there’s monsters, too, as we’re shown in the dystopian novels of Harlan Ellison and, more recently, the monumental Three-Body Problem trilogy by Cixin Liu, whose work ranks alongside Asimov’s Foundation series in scope and imagination. In his trilogy, Liu describes with bone-chilling logic the Dark Forest theory, which postulates that we’d better hope that we never, ever meet any aliens at all. The theory goes something like this:

- All life desires to stay alive.

- There is no way to know if other lifeforms can or will destroy you if given a chance.

- Lacking assurances, the safest option for any species is to annihilate other life forms before they have a chance to do the same.

In his trilogy, Liu describes a galaxy wherein the moment one spacefaring civilization detects another, that civilization will do its utmost to destroy the other without mercy, all in order to ensure its own survival; after all, since when is there any indication whatsoever that alien species would give the least consideration for peaceful coexistence? Remember, while we humans may have morals and principles and perceptions of possible mutual advantage, that does not mean that other species would have the same. If we encountered a civilization and did not immediately destroy that civilization because we believe in coexistence, then we are literally gambling the existence of humanity itself that the other civilization would not exterminate our entire species at the first opportunity.

There is, fortunately, a flaw in that logic.

The Dark Forest theory dovetails with an earlier paper by sci-fi author David Brin addressing the “Great Silence”, the seeming dearth of evidence of extraterrestrial life. While Brin describes several possibilities for the Great Silence, like Liu, one of his postulations is that the reason we hear nothing from extraterrestrial civilizations is that the only sure way for a space-faring civilization to avoid extermination is to remain perpetually hidden, undetected by other civilizations.

But there’s another factor that no one since H.G. Wells seems to have mentioned.

The Martian Conundrum

In 1938, Orson Welles, a young actor who was already making a name for himself on radio, stage, and screen, broadcast a radio play called War of the Worlds. My grandmother remembered it and told me how some became panicked even where she lived at the time in the Mississippi Delta. I had an album of the play and while Welles took great artistic license with most of the story, the plot was essentially the same as H.G. Wells’ novel: Martians came, Martians conquered, Martians got completely wiped out by Earth’s pathogens against which the Martians had no immunity.

Would that be possible? I remember thinking at the time, “Come on now, if the Martians were smart enough to be able to cross interplanetary space with enough force to take over our entire planet, surely they would have been smart enough to take precautions to avoid infection by our bacteria, right?” That’s a plot hole big enough to drive a Bolo through! (One wonders how many readers will get the reference)

I remember that same question occurred to me time and again while reading other sci-fi novels over the years. How could all the leading lights of sci-fi (except for H.G. Wells himself) have missed it? Is it the all-too-human habit of hubris? Or perhaps it’s one of simple practicality, since it’s sorta difficult to write a sci-fi novel about exploring Arrakis or Tatooine or Vulcan if one has to worry about perpetually keeping one’s characters in hermetically-sealed spacesuits just to set foot on the planet, much less live there.

Such may well be the reality. Our own planet Earth is teeming with life, from bioaerosols (microbes that live in our atmosphere) down to microbes found in bore-hole samples from hundreds of meters deep within Earth’s crust, perhaps even as deeply as within Earth’s mantle, and everywhere in between. In other words, even if aliens came to earth and wiped out every living thing on the surface even down to the bacteria, it would for all intents and purposes be flatly impossible for them to wipe out all of Earth’s native life…which means that unless those same aliens are somehow guaranteed to be immune from any of the innumerable microbes and bacteria and viruses existing and constantly evolving on earth, any serious attempt at colonization is sure to be an exercise in futility. Chances are almost certain (as in the plot hole I described above shows) that if a civilization can cross the deeps of interplanetary or interstellar space, that civilization would already realize that if life already exists on a planet, it would be a great waste of time and resources to try to colonize that planet.

In H.G. Wells’ novel, the Martians learned this lesson the hard way. Let’s call this the Martian Conundrum.

Implications for Space Exploration

The Martian Conundrum does not nullify Dark Forest theory, for there are (I assume) other civilizations out there, those civilizations still want to keep on living, and those civilizations might well believe that their best chance at survival is by wiping out any other civilization they meet. What the Martian Conundrum does mean is that there is a further limit on what planets may be colonized. For humans, some (but not all) of the limits are:

- Planets must be within the “Goldilocks zone”, the habitable range neither too close nor too far from the star it orbits, so that its surface temperature would be compatible with the existence of liquid water.

- Planets must be oxygen- and water-rich, and where the atmosphere is (or can be adjusted to) a mixture which our bodies can tolerate. Even then, the oxygen level must be neither too low nor too high, the nitrogen level must be within acceptable limits, and so on.

- The planet must orbit a star which is stable. For instance, Proxima Centauri (the closest star to our own solar system) is a red dwarf that apparently has at least one planet within the habitable range, but just last year Proxima Centari unleashed a solar flare which was visible from Earth’s telescopes. This greatly diminished the likelihood that we could ever colonize a planet in that system.

- The planetary system must not be subject to significant exposure to radiation emitted from other stellar objects e.g. neutron stars, magnetars, unstable stars, and even black holes (radiation is emitted from matter falling into the black hole).

Add to all the above this implication of the Martian Conundrum:

- The planet must be completely sterile. Completely, utterly barren…but with water and acceptable air, of course.

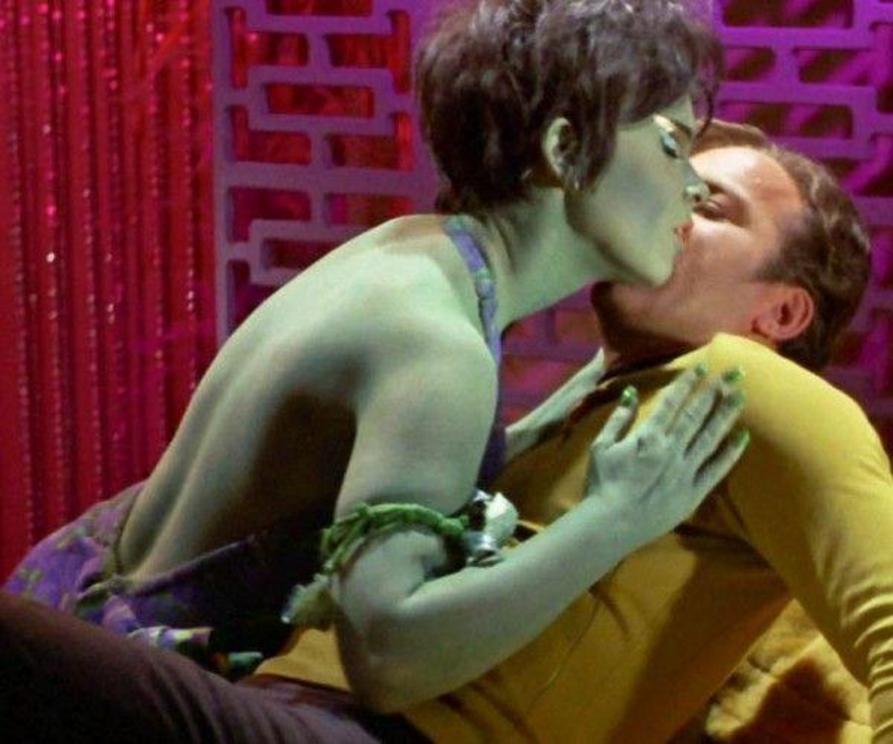

So much for dreams of Captain Kirk having a different alien girl in every interstellar port.

Hey, Captain Kirk was just doing what we sailors have always done.

This doesn’t mean that all hope of humanity spreading throughout the stars is lost. What it does mean is that the percentage of planets that would meet such a list of requirements is minuscule indeed. Fortunately, there’s 250 (+/- 150) billion stars in the Milky Way galaxy. That makes it pretty much certain that there are other habitable planets out there just waiting for us to arrive. Unfortunately, planets (like all other things of value) fall under the iron law of supply and demand: every spacefaring civilization would want more of those vanishingly-rare habitable planets. Of course, what’s habitable for humanity isn’t automatically habitable for any other interstellar species…but if another species is looking for the same kind of planet, then a war of extinction is all but guaranteed.

That’s a truly terrifying prospect, one which would seem to increase the likelihood of Dark Forest theory.

The Glass Is Half Full

Earth’s biosphere has suffered quite a few mass extinctions (here’s a list of the top five). Each time, many millions of years passed before the next one. Between each mass extinction, there was an opportunity not just for life to evolve and flourish, but also for intelligence to grow, for the development of civilization itself. As far as we know, in Earth’s five billion-year lifespan, it’s only within the last few tens of thousands of years - a relative blink of an eye - that any civilization has ever existed on Earth. On those planets where life actually develops, Earth’s experience would infer the following:

- Life may develop, but it may never evolve past the single-cell stage.

- Multicellular (or macrocellular) life may develop, but may never become sufficiently mobile and aware e.g. what we consider plant life.

- Life forms may become mobile and aware, but may never develop tool use. For instance, there is growing indication that quite a few animal species (and even insects) are self-aware, if the “mirror test” is accurate. Just because a living being is mobile and self-aware does not mean it sees any need to use tools at all.

- Life forms may become mobile, self-aware, and use tools, but this does not mean that they would ever want to leave the surface of their planet. The very idea of reaching the stars may seem like so much stuff and nonsense to them.

The above inferences would in turn infer that most (or all) life-bearing planets undergo periodic mass extinctions, that the rise of intelligence and civilization is very rare indeed (and even those may not include an ethos of exploration outside the confines of the planet). Even for those civilizations which desire to reach the stars, there is a growing school of thought that any such civilization must first complete its passage through the Great Filter which may be comprised of any of a number of challenges from resource depletion to internal conflict to ecological collapse due to lack of biological diversity.

Life that can escape the confines of its home planet, then, is the rarest life of all. Out of all the uncountable millions (billions?) of species of life that have existed on Earth alone, only Homo Sapiens is (presently) capable of spaceflight…and that only within the past several thousand years, a mere flash in the pan in geological terms.

If such rarity is the norm rather than the exception in the unimaginable vastness of interstellar space, if intelligence leading to spaceflight and the desire to spread across the stars is not only vanishingly rare but happens only in that metaphorical blink of a geological eye, then it should be no surprise that the aliens haven’t shown up in overwhelming force to exterminate humanity, steal our planet’s resources, and take our precious bodily fluids.

Yes, it is conceivable that another civilization may be extremely long-lived, but if the past century has taught us anything, it’s taught us that the higher the level of technology, the faster knowledge and understanding will grow, and the faster technology will advance. When a civilization is able to build an interstellar empire, unless something (like, say, a sudden loss of a resource required to maintain that empire e.g. “spice” in the Dune series) causes that empire to stagnate or crumble, the level of technology of that empire would only continue to advance at an ever-increasing rate. How far could the technology advance? What are the limits of technological advance, if any? And once a civilization has reached such a level, how much time will really have passed since its early ancestors looked up at the night sky and wondered what those blinking lights really were? If humanity’s experience is any indication, in cosmic terms, not much time at all will have passed from the discovery of fire to the heights of interstellar empire (and whatever comes afterwards).

The fear, then, is not that there are other species capable of building an interstellar civilization that adheres to Dark Forest theory and covets the same kind of planets we humans do. The only fear must be that such a civilization inhabits the same neck of the galaxy that we do, and that their civilization, having also taken place in a cosmic-scale flash in the pan, is concurrent to our own nascent interstellar civilization.

For that reason, then, let us not listen overmuch to those who would have us fear what may await us in the endless night of the Dark Forest, but instead, (to butcher Nick Fury’s phrase from the first Avengers movie) until such time that humanity itself comes to an end, we should act as though humanity will continue to advance and spread.