NASA had high-res images of the Moon in the '60s, so why couldn't we see them?

It's fun to think about how much we achieved with the technology of the 1960s. We landed on the moon thanks to calculations done on paper with a computer woven by hand that had a small fraction of the processing power of the phone in your pocket. So it doesn't seem strange that the images of the moon we had back then were grainy and low quality. Except they weren't. The orbiters that photographed the moon in the 1960s sent back images that were stunningly high-resolution, even by today's standards. It's just that we couldn't access them until recently.

Say Moon Cheese!

In 1961, President John F. Kennedy proposed a lofty goal: by the end of the decade, the United States would put a man on the moon. Before that could happen, of course, we had to know what we were dealing with. That's why NASA started by launching unmanned orbiters to map the moon and find a suitable landing site. Through 1966 and 1967, the Lunar Orbiter Program sent five spacecraft to take photographs of the lunar surface. All five achieved their objectives, and all five died a hero's death by crash-landing on the moon to avoid interfering with future spacecraft.

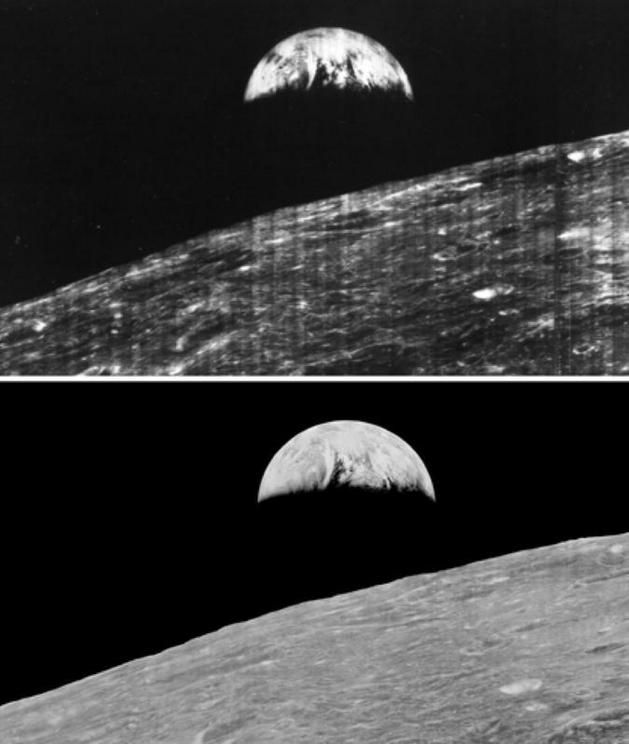

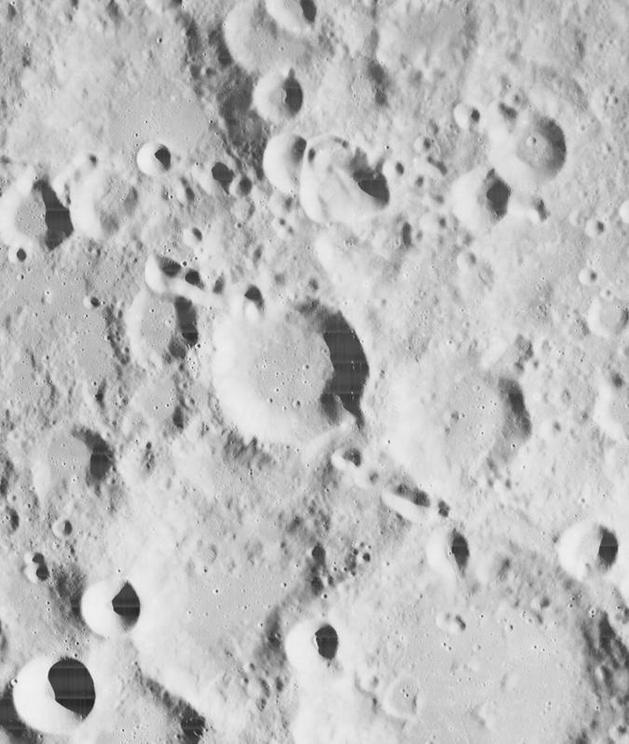

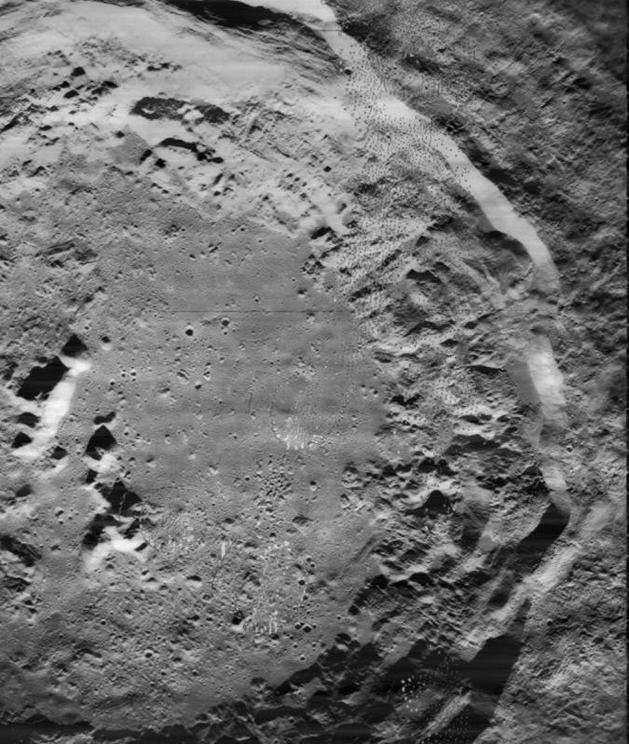

Just what they accomplished boggles the mind. The orbiters mapped 99 percent of the moon's surface with a minimum resolution of 60 meters. That is, they photographed nearly all 38 million square kilometers in such high quality that you could make out the wingspan of a Boeing 747 (that is, if any could fly in the lunar atmosphere). Some of the orbiters did even better, reaching a jaw-dropping resolution of 1 meter. That's not all; because digital photography hadn't been invented, each orbiter had to develop the film, scan the photograph like a fax machine, and then beam the analog data back to Earth.

That data was recorded onto magnetic tape inside of a refrigerator-sized device that was housed in one of three receiving stations in Australia, Spain, or California. They were printed on pieces of paper so enormous that NASA had to rent out old churches to have the room to hang them up for analysis. Of course, the public didn't need this kind of detail, so the images that were released were considerably smaller. Nobody intended those low-quality images to be all we had for decades, but because of some pred

NASAictable government setbacks, that's what ended up happening.

NASAictable government setbacks, that's what ended up happening.

NASA

NASA

McMoon

Once the images were printed, the tapes were placed in storage in Maryland and forgotten about. (This is nothing new for NASA; the original Apollo 11 footage was accidentally taped over.) In the 1980s, Nancy Evans, co-founder of the NASA Planetary Data System, and Mark Nelson from Caltech set out to collect the analog tapes and see if they could digitize the data. That's when things went south; after collecting the analog data, their restoration project lost funding and they had to stop trying. Evans eventually retired and Nelson went back to private industry. Even so, they bought up the tapes and tried raising funds to continue their project as private citizens, but didn't raise enough and the tapes were left sitting in a barn in California.

NASA

NASA

Finally, in 2007, Evans made one last-ditch effort to find someone who would carry on their project. Those people were space entrepreneur Dennis Wingo and NASA engineer Keith Cowing, who began self-funding their own project, the Lunar Orbiter Recovery Project, to restore the images. They set up shop in an abandoned McDonalds, rebuilt the tape drives, digitized the data, and used that data to manually reassemble every image in Photoshop. When they successfully reproduced the famous Earthrise image, they got NASA's attention — and their funding.

After bringing thousands of high-resolution images back from the dead, the Lunar Orbiter Recovery Project completed its mission at the end of 2017. Today, the images are freely available to the public on the NASA website and in the National Archives. Check out a few of our favorites below.

NASA

NASA

NASA

NASA

NASA

NASA

NASA

NASA

Video can be accessed at source link below