Ice Age footprints of mammoths and prehistoric humans revealed for the first time using radar

The mammoth lumbers through our imaginations when we think about the world during the most recent Ice Age. They’re just one of many giant creatures that our ancestors lived alongside and which became extinct when the climate changed. The giant ground sloth – a large herbivore which was endemic to the Americas – is another.

We can study these extinct animals from their bones – but also from the preserved footprints they left in mud. But these footprints are often hard to find – and while they can tell us about the presence of an animal, they don’t always tell us much about the animal itself, like how it walked, for instance. The giant ground sloth was unusual in that it walked on the outside of its feet.

Alkali Flat in New Mexico, USA. Ancient footprints of bygone creatures are preserved here.

Alkali Flat in New Mexico, USA. Ancient footprints of bygone creatures are preserved here.

To help us, we turned to a new method which geologists and archaeologists use to image the hidden subsurface. Ground penetrating radar was first used during the Vietnam War to reveal bunkers below ground. Today, engineers use it to spot cracks in railway tracks and girders. It works by sending signals into the ground which bounce back to reveal subsurface structures. It can be used for imaging big stuff, including buried walls in ancient ruins, but in our new study, we used it to find buried animal tracks from the Ice Age.

Our research team has been working for several years at White Sands National Monument in New Mexico in the US where one of the largest collection of vertebrate animal tracks from the Ice Age can be found. These tracks are preserved on a dried lake bed called Alkali Flat. Because they’re so difficult to make out, they’re locally referred to as “ghost tracks”.

Not only were we able to identify and map large tracks made by big animals such as mammoths and giant ground sloths, but to our surprise, we could also see those of the human hunters that stalked those animals. Imaging footprints of Ice Age giants, and their hunters, without excavating the tracks has huge advantages for their conservation.

Much of Alkali Flat is also used by the White Sands Missile Range, where the American space programme began and the first nuclear bomb was detonated. In places, missile debris litters the ground. Being able to map where most of the tracks are will help prevent them from being erased.

Human footprints from the last Ice Age at White Sands National Monument in New Mexico.

Human footprints from the last Ice Age at White Sands National Monument in New Mexico.

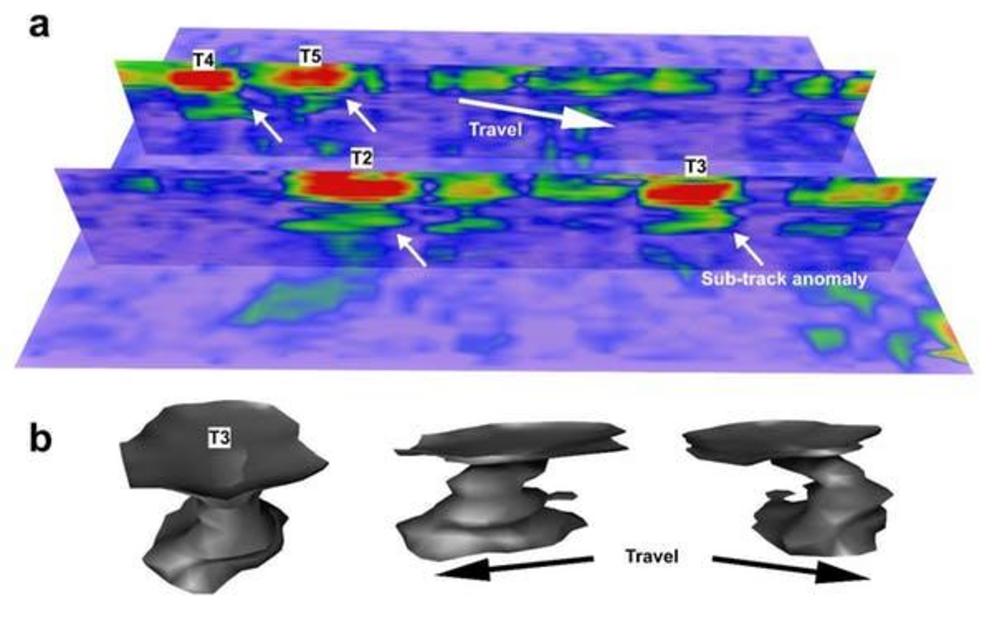

We also noticed something interesting beneath the mammoth tracks in the radar data. Below the base of the footprint, we consistently saw something resembling a hook in the radar image. This was completely unexpected. We weren’t sure what this was at first, but suspected that it might be due to the sediment below being compressed by the footprint. If so, this could provide crucial information about the way the animal walked. If this was indeed a pressure record, then it would likely match the pressure record from a close relative, like an elephant.

Foot pressure data for elephants, by the way, are rare – you can imagine how hard it is to get them into the lab and walking on delicate scientific instruments. Thanks to colleagues from the Royal Veterinary College in London and Monash University, we got our hands on some of this data. The pressure record for elephants turned out to be similar to the hook-like structures revealed in the radar data beneath the mammoth tracks. This led us to conclude that the radar was not only picking out the shape of the footprint, but also giving us much more data on the pressure exerted by the foot on the ground as the mammoth walked.

The pressure data from the mammoth footprints closely resembled those of modern elephants.

The pressure data from the mammoth footprints closely resembled those of modern elephants.

For scientists studying the way extinct animals walk, this was very exciting. It’s the equivalent of getting an extinct animal to come into the lab and walk on a force plate. Best of all, the radar imaging allows us to study how these ancient creatures walked without having to disturb the footprint itself.

We think we’ll be able to use the same technique at other sites to image the pressure pattern beneath a dinosaur’s foot, just as if we’d managed to bring a living specimen into the lab. We should also be able to use this technology to map human footprints at other sites, especially where digging could be disruptive. There are famous sites, such as Laetoli in Tanzania, where footprints of the oldest human ancestors can be found. We’re not quite there yet, but given the right circumstances, we think it’s possible.