Artificial womb helps premature lamb fetuses grow for 4 weeks

Extremely premature lambs have been kept alive in an artificial uterus for four weeks. The system uses a fluid-filled plastic bag and could be used for premature babies within the next three years.

“We’ve developed a system that, as closely as possible, reproduces the environment of the womb and replace the function of the placenta,” says Alan Flake at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania, who led the study.

“It is fascinating,” says Neil Marlow, at University College London. “People have been trying to do this for ages.” But he says the system will have to undergo years of testing to be sure it is safe for babies.

Flake and his colleagues developed their system with babies in mind. Being born extremely prematurely is the most common cause of death in babies. Infants born at 22 to 24 weeks, instead of the full 40 weeks, have only a 10 per cent chance of survival, says Flake.

Bag of fluid

Those that survive are vulnerable to a host of disorders, and can develop lasting disabilities, such as poor vision or hearing or cerebral palsy. “They have very immature organs,” says Flake. “They’re simply not ready to be born yet.”

Babies supported in incubators are prone to infections, for instance, and the gas ventilation that is needed to help babies breathe can leave them with lung damage.

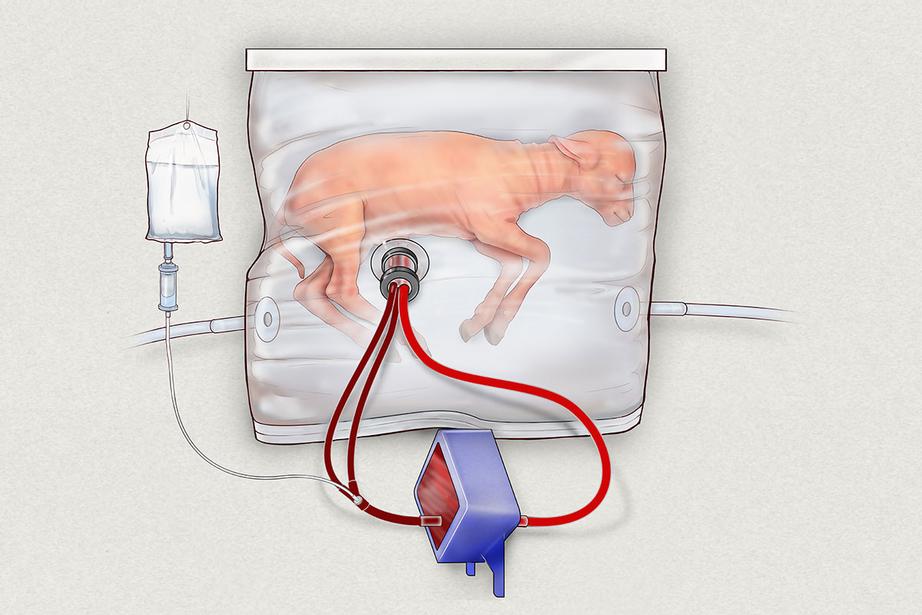

But the plastic bag system provides a sealed environment that should protect a fetus from infections. To mimic the environment of the uterus, the team fill their bags with fluid comprising water and salts.

Premature babies are prone to infection

Children's Hospital of Philadelphia

In place of a placenta – which supplies a healthy fetus with oxygen and other substances – the team connected oxygenator devices to the umbilical cords of the developing lambs. Instead of pumping oxygen into the lambs, the team developed a technique that uses the animals’ own heartbeats to drive the collection of oxygen from the device.

They hope that providing oxygen in this way would be better than the ventilators currently used for premature babies, which can damage their lungs.

Bottle-weaned

In their experiments, the team used lambs that were 15 and 17 weeks into the full 21-week gestational period for sheep. These were removed by Caesarean section, carefully placed into the bags, connected to the oxygenators, and then closely monitored.

The lambs were kept in the bags for up to four weeks. Most of them were then euthanised and examined. All of the lambs appeared to show healthy development, and the team found no abnormalities in the lambs’ brains and lungs. “These animals are, by any parameter we’ve measured, normal,” says Flake.

Some of the lambs were “born” – removed from the bags and bottle-weaned. The oldest is now a year old and is doing well, say the team.

They are now working with the US Food and Drug Administration to develop a version of the device for extremely premature human infants. Their plan is to support babies born at around 24 weeks, until they reach around 28 weeks. By this point, their odds of survival are much higher, say the team. This is a “very reasonable” plan, says Mark Turner, at the University of Liverpool, UK.

However, Turner is cautious of the team’s aim to trial the device on babies within three to five years. “I have concerns about getting the details just right,” say Turner. Some treatments for premature babies have previously been rushed through, only for it to be discovered later that they are harmful.

In the 1960s, for instance, babies were often given too much oxygen. This disrupted the formation of blood vessels, in some cases causing the retina to be separated from the back of the eye. “Several thousand children went blind because of that, including Stevie Wonder,” says Turner.

Human trial

If the team can get the system working for human infants, it would be useful for only about half of the babies that are born extremely prematurely – those that can be delivered by C-section.

For their human device, Flake’s team hope to improve the fluid that babies will be bathed in. Amniotic fluid contains nutrients and growth factors, as well as fetal urine. The team plan on adding substances that are known to aid the development of the gut, for instance.

The human device will look different, too. “I don’t want this to be visualised as fetuses hanging on the wall in bags,” says Flake. He says the device will eventually look like an incubator – with a cover and a dark interior. He also plans to make the device “parent-friendly”, allowing parents to communicate sounds to the baby and to see it with a camera.

Marlow says this is an important consideration, as having a premature infant can be extremely distressing for parents.

On the whole, Marlow is optimistic about the device, but shares similar concerns to Turner. “Anything that is more gentle, and interferes in normal development as little as possible, is to be welcomed,” says Marlow. “But we need to keep an eye on the risks.”

Journal reference: Nature Communications, DOI: 10.1038/ncomms15112