Oxford University scientists gave babies trial TB vaccine 'that did not work on monkeys'

Oxford University is embroiled in an ethics row after scientists were accused of questionable conduct over a controversial trial of a new vaccine on African babies.

Professor Peter Beverley, a former senior academic at the university, complained that scientists planned to test a new tuberculosis vaccine on more than a thousand infants without sharing data suggesting that monkeys given the immunisation had appeared to “die rapidly”.

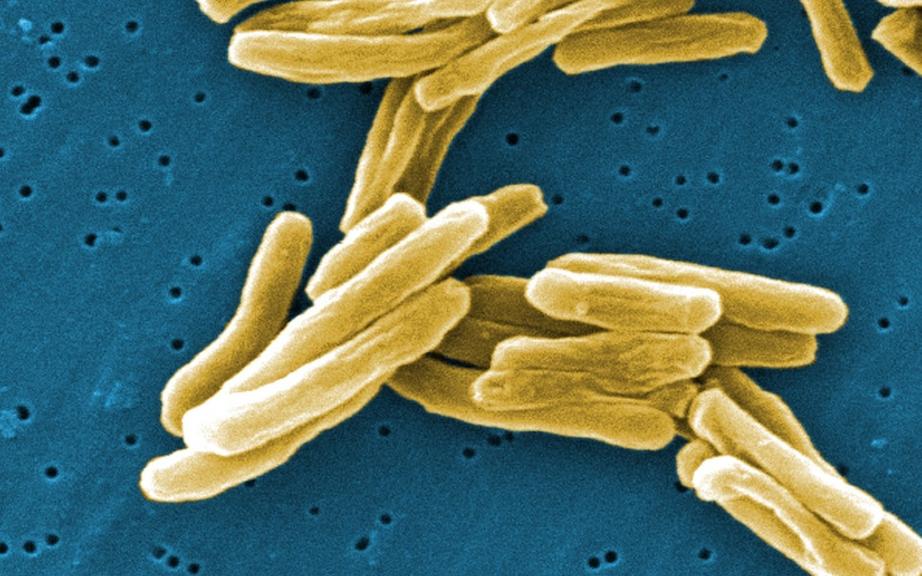

The Tuberculosis bacteria

The Tuberculosis bacteria

“Certainly here in this experiment there was no evidence whatsoever that this is an effective booster vaccine,” Prof Beverley said.

He claimed the information was not given to regulators when an application to do the trial was initially submitted.

In the monkey study, five out of six of the animals infected with TB who were given the experimental vaccine had become “very unwell” and had to be put down.

An information sheet given to families in South Africa participating in the trial said the vaccine had been tested on animals and humans and was “safe and effective” in animals.

Professor Jimmy Volmink, Dean of the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences at Stellenbosch University, told The Telegraph the information sheet did not appear to reflect the evidence from the monkey study, which was "not right".

He said people affected by tuberculosis were often poor and "not very highly educated", making it particularly important that they were given "clear, understandable information."

Almost 1,500 babies in South Africa received the new jab and parents were paid in the region of £10 for taking part.

The South African regulator which approved the trial admitted to this newspaper that the information sheet given to parents “could be construed as misleading”, raising questions about whether families were sufficiently informed.

The scientists at Oxford who carried out the trial maintain that the jab was safe for children and that their experiment was approved by several regulators in advance.

They said they followed the infants’ development for two years after the immunisation was given – a time period approved by the regulators.

The monkey study that concerned Prof Beverley began in November 2006 and the application to test the vaccine in the Western Cape was submitted 18 months later.

Around this time, Prof Beverley said he heard that the animals in a study had to be euthanized “rather rapidly”.

All the monkeys were infected with TB, but one group was given the widely used BCG jab, a second was given no immunisation and a third was given BCG plus new vaccine.

The baby trial began in July 2009 and almost half of the 2,800 infants taking part were given the new jab.

In 2013, the outcome of the trial on the infants was announced and concluded that the new vaccine offered no increased protection.

Professor Beverley, a principal research fellow at the University of Oxford until 2010, complained formally to the university.

An inquiry was launched and concluded that although there had been no wrongdoing, it “would have been good practice for the potentially adverse reaction observed in the monkey experiment to be reported to the authorities in a more timely fashion.”

Professor Helen McShane, one of the lead scientists who developed the new vaccine, has said that the purpose of the monkey study was to “test the aerosol delivery” to the animals, not to “yield safety information”.

She said it was a “failed experiment” because “there was no difference “ between the groups.

Prof McShane told the Telegraph that there was no delay in providing data from the monkey experiment to regulators.

She said she did not think that families in South Africa were exploited and that regulators had signed off the information sheet that was given to parents.

She added that the monkey trial contained a “limited” number of animals and Professor Beverley was “disgruntled”.

South African Medicines Control Council, which was one of the regulators who approved the trial, said that a “large body of data” – apart from the monkey experiment and which included previous human trials – was considered as part of the approval process.

They also said that the monkey experiment was “not a trial of the vaccine in monkeys” and that “there was no suggestion that the vaccine was unsafe in the monkeys or that it had caused disease or death”

However, when asked about the information sheet that was given to parents, the regulator said, “In retrospect the information on efficacy achieved in the animal studies could be construed as misleading”, although the “evidence of safety in the previous human studies was fairly reported”.