Marijuana farms expand in Paraguay reserve despite government crackdowns

- Approximately 600 metric tons of marijuana was seized by agents of Paraguay’s National Anti-Drug Secretariat (SENAD) in an operation in the heart of the forests of Morombí Reserve, between the departments of Canindeyú and Caaguazú.

- Over eight days, some 70 officers destroyed 202 hectares of marijuana and dismantled 23 camps set up by drug traffickers.

- But sources say this is just the tip of the iceberg and many more illegal marijuana farms are pockmarked throughout Morombí, increasing by the day. Satellite data support this, showing the reserve’s deforestation rate skyrocketed in 2019 and continues to climb into 2020.

This story is a collaboration between La Nación and Mongabay Latam. It is the third installment of a five-part series on illegal deforestation for marijuana production in eastern Paraguay. Read the first and second parts.

TAGUATÓ, Paraguay — At around 10 in the morning, an Armed Forces helicopter lifts off from an empty field in eastern Paraguay that serves as a temporary base for a team comprised of agents from Paraguay’s National Anti-Drug Secretariat (SENAD), the Public Prosecutor’s Office and the National Forestry Institute (INFONA). It is a clear-skied February morning and the heat is already unbearable.

For eight days, some 70 agents have been working in this area of Morombí Natural Reserve, a protected area comprising 24,800 hectares and which forms part of the National System of Protected Wild Areas of Paraguay. The reserve is located in the Upper Paraná Atlantic Forest, an endangered ecoregion of which less 10% remains today.

The helicopter flyover reveals a green landscape dotted with rectangular patches of bare earth where the forest has been destroyed to plant marijuana. They appear small from above, but the reality is different down below. Commander Aldo Pintos, of SENAD, says the average plantation is four to five hectares in size, and that they have found some that are upwards of 10 hectares.

After a 20-minute journey, the helicopter lands on a patch of once-forest that had been cleared by drug traffickers. The breeze mingles with the dust from the ground and the ashes of what, several days ago, was still dense forest. What remains are dismembered branches, charred trunks and piles of charcoal scattered across the barren ground.

In one plantation, marijuana plants are over two meters (6.5 feet) tall. The terrain is rough and uneven and in the rows between crops lie tree trunks of various sizes. The distinctive smell of recently cut marijuana fills the air.

“When we burn it the smell is much stronger,” says one of the officials, wiping away sweat with his military-issue bandanna as he hacks away at the plants.

Nearly 4,000 hectares lost

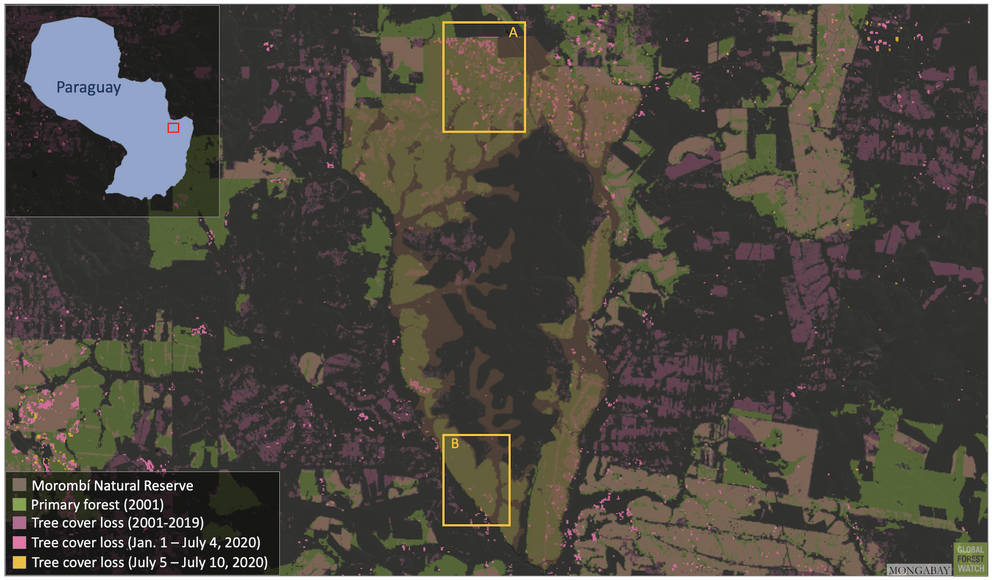

Law 2524, also known as the “Zero Deforestation Law,” was enacted in 2004 and prohibits the felling of trees in Paraguay. Despite this law, however, satellite data from the University of Maryland show Morombí lost nearly 4,000 hectares (9,900 acres) – or 15% – of its tree cover since between 2004 and 2019, with most of that loss coming after 2014. Last year saw a huge increase in the reserve’s annual deforestation rate, more than tripling the amount of forest lost in 2018. Other protected areas in eastern Paraguay show similar trends.

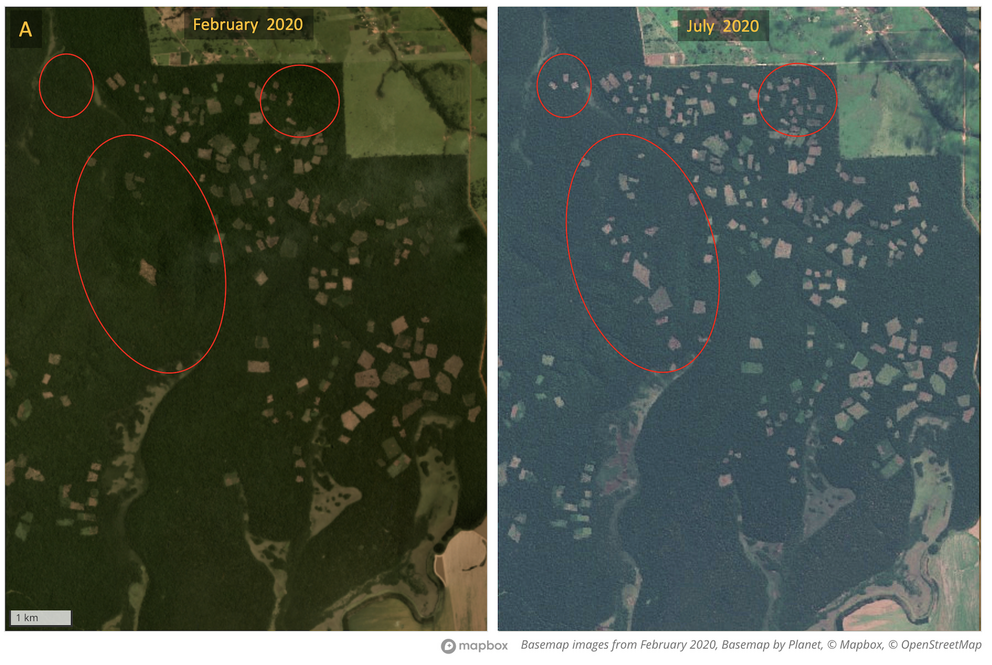

Satellite data and imagery also show that clearing has since resumed in the northern part of Morombí Reserve, where the February intervention took place.

Satellite data show large areas of Morombí Natural Reserve’s primary forest have been deforested in 2020.

Satellite data show large areas of Morombí Natural Reserve’s primary forest have been deforested in 2020.

Satellite imagery shows a surge in clearing activity since the operation in February.

Satellite imagery shows a surge in clearing activity since the operation in February.

Deforestation has also spread to the southern part of the reserve.

Deforestation has also spread to the southern part of the reserve.

Morombí is home to a multitude of species of plants and animals. According to the Morombí Foundation’s records, the reserve provides habitat to jaguars (Panthera onca), pumas (Puma concolor), bush dogs (Speothos venaticus), South American coatis (Nasua nasua), white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) and peccaries (Tayassuidae), among many other mammals. Some 300 species of birds have been recorded in the reserve, several of them endangered, including the harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja), the vinaceous-breasted amazon (Amazona vinacea) and the bare-throated bellbird (Procnias nudicollis).

There is also a wide variety of native trees like the trumpet tree (Tabebuia), jacaranda (Jacaranda mimosifolia), cedar (Cedrela fissilis) and Ibirá-pitá (Peltophorum dubium), all of which are coveted by timber traffickers. After cutting down the trees to clear land for marijuana, some of the trees are transported out of the reserve to be sold at timber markets, while less valuable wood is burned in earthen stoves to transform it into charcoal.

“Clearing the area like this takes time,” a SENAD agent told Mongabay and La Nación. The agent added that after logging and burning, the traffickers must wait at least two weeks before they can plant marijuana.

Dozens of illegal marijuana farms carved from the forest pockmark Morombí Reserve.

Dozens of illegal marijuana farms carved from the forest pockmark Morombí Reserve.

“The real problem with these illegal plantations is that all this deforestation is obviously being carried out without any management plan,” says Víctor González Bedoya, one of INFONA’s legal advisers who is accompanying the operation. “We do not know what kind of plants are being lost. There is no project, nothing. They destroy everything at once and that’s it.”

SENAD is leading an initiative entitled “Canindeyú – Caaguazú I” in which various public institutions are working together in order to destroy illegal plantations in Paraguay’s Atlantic Forest reserves and parks, and apprehend those responsible. The operation also involves the National Forestry Institute, which is providing native trees for the reforestation of affected areas, along with the Ministry of Environment and the Public Prosecutor’s Office. However, while large amounts of marijuana have been destroyed and seized, judicial records show not a single person was found responsible and charged for illegal deforestation in the departments of Canindeyú, Caaguazú, Caazapá and Itapúa between 2004 and 2020.

Trees that are not sold end up in the clandestine charcoal ovens in Morombí Reserve. According to the public prosecutor, the charcoal is often smuggled into Brazil.

Trees that are not sold end up in the clandestine charcoal ovens in Morombí Reserve. According to the public prosecutor, the charcoal is often smuggled into Brazil.

According to judicial statistics, in these four departments, which include Morombí along with Mbaracayú Reserve, San Rafael National Park/Proposed National Reserve, and Caazapá National Park, 31 cases of illegal logging, timber trafficking and burning were recorded in 2019. However, of these cases, only one involved a reserve: Morombí, where an investigation into illegal timber extraction is being conducted.

This year seems to be following the same pattern. As of May 2020, only one case had been filed – in Curuguaty, a district in Canindeyú, the Public Prosecutor’s Office is investigating an alleged case of timber trafficking.

Culprits flee the scene

Commander Pintos has been with SENAD for 15 years and said this isn’t the first such operation he’s been involved in in the region. He said apprehending those responsible is a considerable challenge.

“When we leave the barracks, [the drug traffickers] already know we’re on our way,” Pintos said. “By the time we arrive they have already left”

SENAD agents destroyed 202 hectares of marijuana during an operation in Morombí in February.

SENAD agents destroyed 202 hectares of marijuana during an operation in Morombí in February.

“Above all, we want to give the message that the state is present here,” said González Bedoya, who works for INFONA, while inspecting a marijuana plantation during the February operation. For SENAD agents, this work has long become almost a routine: they destroy one hectare of illegal crops today, and another area in the same reserve is cleared tomorrow.

There have been human settlements in the areas of influence of Paraguay’s reserves and parks for years. Some 563,000 people live in the department of Caaguazú and another 195,000 live in the department of Canindeyú. The Morombí Reserve also has a history of farming settlements laying claim to part of the protected area. State agencies claim that some residents of these settlements are complicit in the marijuana trade, at least indirectly.

The public prosecutor in charge of operations in the Morombí Reserve is Osvaldo García, from the Caaguazú Anti-Drug Unit. García is also a representative of the Public Prosecutor’s Office in the department of Caaguazú. According to García, one thing that would help reduce illegal deforestation in reserves would be to spread awareness of the problem by employing more environmental prosecutors from the regions where these crimes are happening. He also urged more buy-in from the government.

“I think that people in Asunción have no idea of everything that goes on here,” Garcia said, adding that “more state agencies need to be involved here because we are dealing with a criminal organization, a system of organized crime that works with timber, charcoal and marijuana.”

Tree trunks that cannot be removed from the land are burned.

Tree trunks that cannot be removed from the land are burned.

But in this part of the country, the Public Prosecutor’s Office reportedly has very few resources. Sources say it lacks the technology needed to trace illicit activities or receive deforestation alerts via satellite.

“We do what we can on the ground,” García said. Despite the obstacles, he believes they are making progress.

García says 120 people connected to drug trafficking in eastern Paraguay have been convicted in the last three years. However, the judiciary has no records of cases that involve environmental crimes linked to marijuana.

García says that more recently it has become increasingly common to see minors involved in the trade. This, he said, “is a social problem. It can no longer be treated as simply a matter of drugs or the environment.”

In the first part of operation “Canindeyú – Caaguazú I,” 50 active marijuana plots were found in Morombí Reserve, corresponding to a total of 202 hectares of illegal plantations. Through SENAD’s intervention, some 600 metric tons of marijuana were destroyed. Authorities estimate this equates to a loss of $18 million for the drug-trafficking groups in the region.

Ruth Benítez, who works for INFONA, says that the degraded areas will be reforested with native tree species after the intervention.

Row upon row of marijuana plants grow where a forest once stood in Morombí Reserve as dead trees serve as reminders of what was lost.

Row upon row of marijuana plants grow where a forest once stood in Morombí Reserve as dead trees serve as reminders of what was lost.

As the end of the day approaches, dozens of anti-drug agents are still cutting down marijuana plants with machetes. The only other sound is the engine of the military helicopter, which is returning from the latest flight during which yet more illegal plantations were discovered.

“I hope your report helps to show how the reserve is being destroyed,” said one of the park rangers, adding that he doesn’t expect much to change after this latest intervention – an expectation that seems to have come true, at least in the near term.

This is a translated and adapted version of a story that was first published in Spanish by Mongabay Latam on May 267, 2020.

Editor’s note: This story was powered by Places to Watch, a Global Forest Watch (GFW) initiative designed to quickly identify concerning forest loss around the world and catalyze further investigation of these areas. Places to Watch draws on a combination of near-real-time satellite data, automated algorithms and field intelligence to identify new areas on a monthly basis. In partnership with Mongabay, GFW is supporting data-driven journalism by providing data and maps generated by Places to Watch. Mongabay maintains complete editorial independence over the stories reported using this data.