Kenya’s new digital IDs may exclude millions of minorities

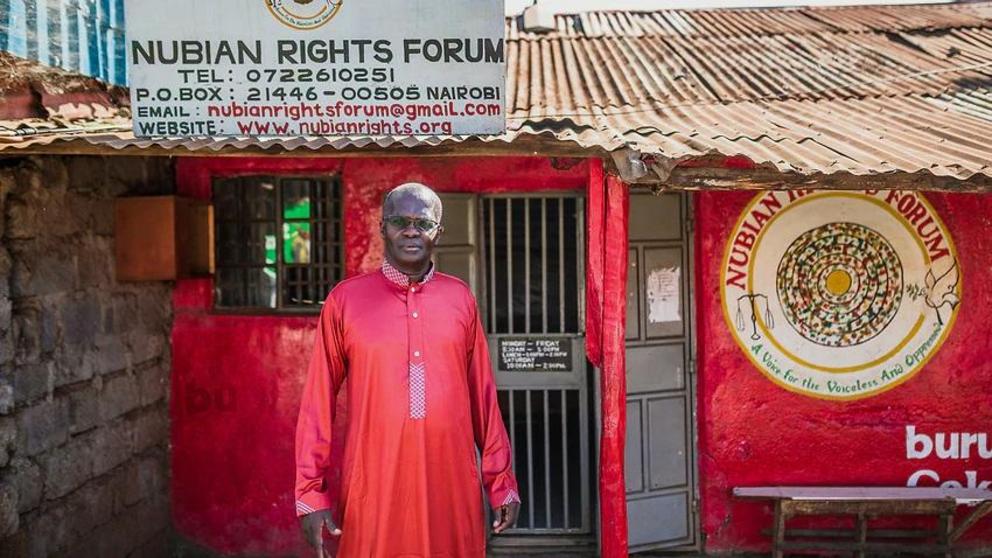

Ahmed Khalil Kafe, who is of Nubian descent, in Nairobi, Kenya on Dec. 20, 2019.

Millions face hurdles in obtaining documents to get a biometric ID card that will be required to function in the country. Without one, “you are totally a living dead,” a human rights advocate said.

For all his 73 years, Ahmed Khalil Kafe lived as a citizen of Kenya.

Born in the capital, Nairobi, Kafe worked as a police officer and even served with the presidential guard, court documents show. But last April, when he tried to register for a national ID in the giant biometric database that President Uhuru Kenyatta has said will be the “single source of truth” on Kenya’s population, he was turned away.

Now, Kafe said, “My life is in limbo.”

In an ambitious new initiative, the Kenyan government is planning to assign each citizen a unique identification number that will be required to go to school, get health care and housing, register to vote, get married and obtain a driver’s license, bank account and even a mobile phone number. In preparation, nearly 40 million Kenyans have already had their fingerprints and faces scanned by a new biometric system that ramped up last spring.

But millions of ethnic, racial and religious minorities — like Kafe, who is a Kenyan of Nubian descent — are running into obstacles and facing additional scrutiny when they apply for the documents required to get a biometric ID. Many have faced outright rejection.

Now the biometric ID plan is being challenged in court by civil rights organisations, which say it is disenfranchising members of minority groups. The high court is expected to rule Thursday on whether the project is constitutional.

“The government is digitizing discrimination,” said Shafi Ali, chairman of the Nubian Rights Forum, one of three civil rights groups that brought the court challenge. Without an ID card and identification number, he said, “you are totally a living dead.”

People gather inside a courtroom in Nairobi, Kenya for a hearing into a new biometric national identification system on Dec. 18, 2019.

People gather inside a courtroom in Nairobi, Kenya for a hearing into a new biometric national identification system on Dec. 18, 2019.

The Kenyan Interior Ministry, which is leading the biometric project — known as the National Integrated Identity Management System — declined to comment on anything about it, citing the pending court case.

Such identity projects are increasingly common and sometimes even lauded by global institutions like the World Bank for their potential to increase access to financial services and ensure transparent elections.

But as in India, where the government has come under withering criticism for forcing nearly 2 million people to prove their citizenship or risk being declared stateless, Kenya’s program has been denounced for further marginalising already vulnerable populations.

“There is the real risk,” said Keren Weitzberg, a researcher at University College London who is studying the biometric program in Kenya, that the IDs “will only reproduce existing inequalities and exacerbate debates over who is ‘really’ a Kenyan.”

Kenya is a diverse country with a history of tensions between ethnic groups. Indians and Nubians, whose ancestors were brought to Kenya as workers by British colonial authorities, have struggled for generations to be accepted as full citizens. Kenyans of Somali descent have faced particular suspicion and discrimination — even being rounded up and held for days in a stadium — in the wake of terrorist attacks by militant group al-Shabab.

In Kenya, to secure a biometric identification number — known as a Huduma Namba, or “service number” in Swahili — adults must provide a national identity card, while birth certificates are required for those under 18.

The Kenyan government has long made it harder — or even impossible — for members of some ethnic groups, among them Nubians, Somalis, Maasais, Boranas, Indians and Arabs, to apply for the documents required for national ID cards.

They may be asked to present land titles or the papers of their grandparents, or be questioned by security agents. And often, they can apply only on specific days of the week or in certain seasons, especially in small towns and rural areas.

Members of some of these communities live along Kenya’s borders, and government officials say they have introduced some measures to keep out those who pose a security risk, or people fleeing war in neighboring Somalia. But the measures also affect pastoralists who cross back-and-forth along the country’s borders, such as the Maasai and Samburu.

The added hurdles have affected at least 5 million of Kenya’s 47.5 million people, leading to delays in processing their ID cards and outright denials, said Laura Goodwin, citizenship program director for Namati, an international legal justice group.

Human rights advocates say that many people were turned away during the biometric registration drive last April and May. If the biometric ID system goes ahead, Goodwin said, millions could end up without identification numbers.

For Kafe, whose Nubian forebears were brought from Sudan to Kenya by British colonial authorities over a century ago, the government’s plan risks rendering him stateless.

He said that he lost his national identity card in a robbery soon after leaving the police service in the early 1970s, and was unable to secure a replacement even after supplying sworn affidavits.

“I lost hope,” he said on a recent morning near his home in Kibera, an urban slum southwest of Nairobi. “I was very disappointed in Kenya.”

Many Kenyans in towns and villages outside Nairobi and other major cities lack papers because their local registration centers are far away. Or they have to wait longer for papers because those centres are overwhelmed.

Meimuna Mohamood is a Kenyan citizen of Somali descent, and lives in the northeastern town of Garissa, along the border with Somalia. Garissa has been the target of repeated terrorist attacks by al-Shabab, including one on the university in 2015 that left 148 people dead. Afterward, government officials vowed to tighten security.

Mohamood has an identity card. But she has not been able to obtain birth certificates — which are necessary for children to get biometric identifiers — for her daughters, who are 5 and 7.

The two girls were born at home, not a hospital, where their births would have easily been recorded. Her efforts to register them have so far been stymied by government officials.

“I keep going back to government offices, and they always say there is something missing,” Mohamood said. “I am afraid for my girls. They are not in any system. I am worried about their future.”

The government has also drawn criticism over the mechanism it used to institute the Huduma project, whose initial cost was projected at over $74 million.

It was introduced in Parliament using a procedure usually reserved for minor changes to existing laws, and its first iteration sought to collect DNA and GPS data, both of which were barred by a court in April. The legislation detailing how the system would work was not published until July, after the registration drive had ended.

The law also imposes fines and criminal penalties, including prison time, for failing to register — which critics have called disproportionate.

“You shouldn’t have to blackmail people into doing things that are for their own good,” said Nanjala Nyabola, author of “Digital Democracy, Analogue Politics: How the internet Era is Transforming Politics in Kenya.”

For Kafe, at least, there may be a glimmer of hope.

After he agreed to testify in court in the challenge to the Huduma program, he said, registration officials visited his home and said they would process his documents.

In September, he was given a “waiting card,” which the government supplies while a national ID is being processed. But it could be months or even years before his identity card is delivered, if he receives one at all.

“When does a Kenyan become Kenyan?” Kafe asked. “We need a system that’s good for all. We need equality.”

Source The New York Times