HCG found in WHO tetanus vaccine in Kenya

... raises concern in the developing world

Thank you to our loyal reader Dr. K.O. for making us aware of this paper.

Open Access Library Journal

John W. Oller1, Christopher A. Shaw2,3, Lucija Tomljenovic2,3, Stephen K. Karanja4, Wahome Ngare4, Felicia M. Clement5, Jamie Ryan Pillette5

1Communicative Disorders, University of Louisiana, Lafayette, USA 2Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Graduate Program in Experimental Medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada 3Neural Dynamics Research Group, Vancouver, Canada 4Kenya Catholic Doctors Association, Nairobi, Kenya 5University of Louisiana, Lafayette, USA

Copyright © 2017 by authors and Open Access Library Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

Received: September 12, 2017; Accepted: October 24, 2017; Published: October 27, 2017

ABSTRACT

In 1993, WHO announced a “birth-control vaccine” for “family planning”. Published research shows that by 1976 WHO researchers had conjugated tetanus toxoid (TT) with human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) producing a “birth-control” vaccine. Conjugating TT with hCG causes pregnancy hormones to be attacked by the immune system. Expected results are abortions in females already pregnant and/or infertility in recipients not yet impregnated. Repeated inoculations prolong infertility. Currently WHO researchers are working on more potent anti-fertility vaccines using recombinant DNA. WHO publications show a long-range purpose to reduce population growth in unstable “less developed countries”. By November 1993 Catholic publications appeared saying an abortifacient vaccine was being used as a tetanus prophylactic. In November 2014, the Catholic Church asserted that such a program was underway in Kenya. Three independent Nairobi accredited biochemistry laboratories tested samples from vials of the WHO tetanus vaccine being used in March 2014 and found hCG where none should be present. In October 2014, 6 additional vials were obtained by Catholic doctors and were tested in 6 accredited laboratories. Again, hCG was found in half the samples. Subsequently, Nairobi’s AgriQ Quest laboratory, in two sets of analyses, again found hCG in the same vaccine vials that tested positive earlier but found no hCG in 52 samples alleged by the WHO to be vials of the vaccine used in the Kenya campaign 40 with the same identifying batch numbers as the vials that tested positive for hCG. Given that hCG was found in at least half the WHO vaccine samples known by the doctors involved in administering the vaccines to have been used in Kenya, our opinion is that the Kenya “anti-tetanus” campaign was reasonably called into question by the Kenya Catholic Doctors Association as a front for population growth reduction.

Subject Areas:

Gynecology & Obstetrics, Women’s Health

Keywords:

Anti-Fertility Measures, Beta-Human Chorionic Gonadotropin, Birth-Control Vaccine, Population Control Programs

INTRODUCTION:

On November 6, 2014, the Kenya Conference of Catholic Bishops (KCCB) which presides over the Kenya Catholic Health Commission (established in 1957 [1] ) issued a press release alleging that the World Health Organization (WHO) was secretly using a “birth-control” vaccine in its anti-tetanus vaccination campaign in Kenya 2013-2015 [2] . A few days later, an article in the Washington Post followed with similar allegations quoting the Kenya Catholic Doctors Association (KCDA) [3] . Such claims from sources in the Catholic Church prompted this case study of the WHO Kenya “anti-tetanus” campaign along with a review of WHO research to develop anti-fertility vaccines1. Many published papers, which we found in the Web of Science and PubMed data bases, document WHO experimental research with various anti-fertility vaccine conjugates [4] - [24] since the 1970s. The published objective of WHO researchers performing the experiments was to engineer one or more “birth-control” vaccines that can, with known reliability, produce and maintain infertility indefinitely.

In the background, as a subunit of the United Nations, the WHO has also been pursuing the global objective of reducing world-wide population growth primarily through “family planning” and contraception [25] . In this paper, our main focus is on just one of the WHO contraceptive vaccines [10] [16] [26] and more specifically on speculation about whether or not it was deployed by the WHO in the five administrations of tetanus vaccine in the Kenya campaign of 2013-2015. Here we examine the relevant research and the best laboratory data available to us in order to form our best guess, the informed opinion in which the authors concur, concerning what the WHO may have actually done in the recently completed Kenya vaccination campaign. Acknowledging from the beginning that our investigation involves inferences from incomplete and partial data, it is our opinion that all the parties involved in the “family planning” work of the WHO need to be fully informed.

Because, as we will report here, some of samples of the “tetanus” vaccine used by the WHO in Kenya tested by the KCCB/KCDA contained a WHO “birth- control” component, ethical and moral questions must be raised [27] [28] [29] [30] [31] . First among them is the “do no harm” caveat [32] . If as suspected by the Catholic doctors [33] [34] mothers-to-be were misled into accepting an antifertility vaccine in the hope of protecting their future children from neonatal tetanus, the “do-no-harm caveat” was violated. In receiving up to five antifertility injections any mothers-to-be would almost certainly be robbed of the very children they were trying to protect from neonatal tetanus. If the suspicions were valid, there would also be an ethical breach of the obligation on the side of the WHO to obtain “informed consent” from those Kenyan girls and women [35] [36] [37] [38] . If the patient is conscious and competent, known risks are universally supposed to be disclosed [37] . The underlying principle at issue comes down ultimately to the “Golden Rule” of treating others the way we ourselves would want to be treated [39] [40] . Do adolescent and mature women have the right to know if they are about to receive an anti-fertility vaccine? Or, alternatively, does the WHO have the prerogative to administer such a vaccine as a tetanus prophylactic without disclosing its anti-fertility aspect?2

The type of anti-tetanus “birth-control” vaccine the KCCB and KCDA suspected the WHO of using in Kenya involves the linking the beta portion of the hCG hormone with the active agent in tetanus vaccines which is tetanus toxoid (TT). In fact, WHO biomedical researchers have been working to engineer such an “anti-fertility” vaccine for “birth-control” at least since 1972. Research published in 1976 confirmed that recipients of a vaccine containing βhCG chemically conjugated with TT develop antibodies not only against TT but also against βhCG. The result, first reported by WHO researchers at a meeting of the US National Academy of Sciences [5] , is a “birth-control” vaccine that diminishes the βhCG essential to a successful pregnancy and causes at least temporary “infertility”. Subsequent research showed that repeated doses can extend infertility indefinitely [6] [8] [10] [11] [13] [14] [23] [24] [26] [50] . In the reported clinical trials [10] [13] [14] , researchers systematically avoided administering an “anti-fertility” vaccine to a pregnant woman on the theory that it would cause an abortion as it does in experimental animal models [26] .

The whole hCG hormone consists of two linked sub-units termed α (alpha-hCG) and β (beta-hCG). It is produced in increasing quantities [51] [52] [53] , if all is going well, by the rapidly dividing fertilized egg. The presence of βhCG enables maintenance of the corpus luteum ensuring that it will continue sufficient production of progesterone needed for implantation and maintenance especially throughout the first trimester. Successful implantation on day 4 - 7 after fertilization requires fairly precise amounts and timing of progesterone production [5] [10] [11] [13] [16] [22] which depends in turn on sufficient βhCG.

Because increasing amounts of βhCG are essential to the “cross-talk” required to maintain the early pregnancy, a vaccine containing TT/βhCG conjugate may not only prevent implantation of a fertilized egg, but if an embryo is already implanted, such a vaccine may cause its death. The result of any unexplained (undiagnosed) pregnancy loss is commonly referred to as a “spontaneous” abortion [54] . However, if the loss was caused by a “birth-control” vaccine, represented, as suspected by the Catholic doctors in Kenya, only as a “tetanus prophylactic”, the death of the baby would be owed to the deceptive promise of a tetanus-free live-birth. Therefore, if the suspicions of the KCCB and KCDA were valid, many of the unsuspecting Kenyan mothers-to-be, ones being encouraged by the WHO to ensure a better future for one or more of their own yet unborn children, were actually being deceived to submit their bodies to one or many injections that would keep their own unborn babies from ever being born.

Over the decades since the prototype of the WHO anti-βhCG vaccine was first tested in 1974 [5] , the volume of published research on anti-fertility vaccines has greatly increased. Although WHO researchers claim their TT/βhCG birth-con- trol vaccine is reversible [11] [55] , their on-going research aims to produce a recombinant gene using DNA of either E. Coli [21] or vaccinia virus [9] . Given the power of recombinant DNA to reproduce, long-lasting or even permanent sterility in vaccinated recipients is theoretically attainable.

2. Methodologies and Materials

Following the news reports in 2014 from the KCCB and KCDA claiming that the WHO vaccination campaign advertised to “eliminate maternal and neonatal tetanus” [56] [57] [58] [59] [60] was suspected of vectoring a birth-control product into women of child-bearing age [3] [31] [45] , some of us3 began searching the Web of Science for published research concerning “anti-fertility vaccine”, “birth-control vaccine”, and for “tetanus toxoid AND human chorionic gonadotropin” (sometimes following up titles in the PubMed database). Our question, was whether the WHO was engaged in developing a birth-control vaccine linking TT to βhCG [5] [61] ? What was the research basis, if any, for the KCDA suspicions that the WHO might be using an anti-fertility vaccine in Kenya?

We found a plethora of studies beginning with the linking of TT to βhCG by WHO researchers in the 1970s. We also found policy statements by the WHO and its collaborators stating the geo-political and economic goal of population growth reduction in unstable “less developed countries” (including Kenya), known to be rich in costly mineral resources needed by the developed nations. These initial findings gave credence to the suspicion that the WHO may have disguised a clinical trial of their “birth-control vaccine” in Kenya as an effort to “eliminate maternal and neonatal tetanus” there.

Given the published research confirming the history of the WHO “birth- control” vaccine, the American and Canadian co-authors decided to contact Dr. Wahome Ngare who had been quoted in some of the published reports about the WHO campaign in Kenya. He put the rest of us in touch with Dr. Stephen Karanja, another of the physicians required by the Kenya Ministry of Health to participate in the WHO vaccination campaign. They agreed to join us as co-authors and to provide access to the data from laboratory tests of the vaccine being used in the Kenya campaign. Together with the KCDA they have assured us of the integrity of the chain of custody of the particular samples (carefully apportioned “aliquots”) of WHO vaccine that they were personally involved in collecting, apportioning, and distributing to accredited Nairobi laboratories. In this report, we merely summarize the results of the laboratory tests now in the public domain. We also provide access to all three of the reports presented to the WHO and Ministry of Health in Kenya by the KCCB of the results obtained from the several laboratories [62] [63] [64] . While none of us can verify the chain of custody of the tested aliquots handled by the various laboratories and their employees, however, we hold the opinion based on data in hand, that at least half of the vaccine samples actually obtained from vials being used in the March and October rounds in 2014 tested positive for βhCG.

With all the foregoing in mind, we pursued a five-fold approach in our investigative research. In the following bolded list, we summarize each of our five methodologies with bolded titles corresponding to the five distinct segments by the same titles presented respectively in the Results section that immediately follows the list:

1) Documenting the history and goals of the WHO. Various geo-political and economic reports, and policy statements from the WHO, the United Nations, and affiliated governmental agencies (in particular the U. S. Agency for International Development) set a high premium on contraception for “family planning” in certain “less developed” regions of the world.

2) Examining the published scientific research. News reports from the Catholic Church about the WHO vaccination campaign going on in Kenya spurred us to seek out the published research in professional journals. Was it true that the WHO had been engineering vaccines linking TT with βhCG? This methodology led us to a trail of published research beginning around 1972 growing into many publications cited thousands of times showing that the WHO has been pursuing contraceptive vaccine research as claimed by the KCDA.

3) Tracking the reported events in Kenya. Our third methodology was a form of investigative journalism. Materials consisted of the news reports coming from Kenya set in chronological order with information from the two preceding methodologies on the theory that concordance between such different streams of information is unlikely to occur by chance.

4) Comparing vaccination schedules for tetanus and anti-fertility. Our fourth method involved a “thought experiment” applying the simplest type of mathematical probative tests for a variety of Euclidean congruence [65] . The KCDA claimed that the WHO dosage schedule of five shots administered in six month increments was inconsistent with published tetanus vaccination schedules. So, our simple probative test was to compare the published vaccination schedules for TT, t, with the published schedules for TT/βhCG, β. Calling the schedule used in Kenya, k, and taking “=” to mean congruent, if t ≠ β, but β = k, and k ≠ t, it follows that k is a dosage schedule appropriate to TT/βhCG, the WHO antifertility vaccine. The simple test of congruence of dosage schedules is not conclusive proof by itself, but it is consistent with the opinion of the authors that the WHO followed a dosage schedule appropriate for TT/βhCG in Kenya but inappropriate for TT vaccine.

5) Laboratory Analyses of the WHO vaccines. With the assistance of the KCDA, we analyzed the actual reports of laboratory tests of vials of the Kenya vaccine obtained by the KCDA, as vouched for by Ngare and Karanja, during the actual vaccination campaign. Those laboratory results were systematically compared with analyses of samples provided later by WHO officials allegedly from supplies maintained in Nairobi. Two sources were tested: a) vials of the vaccine obtained by the KCDA from among those being administered by the WHO in March and October of 2014, and b) 52 additional vials handed over by the WHO from supplies in Nairobi to the “Joint Committee of Experts”. Of the samples that co-authors Karanja and Ngare were personally responsible for handling, over half were found to contain βhCG by multiple laboratories and in multiple distinct tests. The KCDA has also provided access to the public domain reports and the technical data published for wider accessibility here for the first time in a professional academic forum. Of the 52 samples provided by the WHO to the “Joint Committee” none were found to contain βhCG, and of those, 40 vials delivered after a lapse of 58 days (November 11, 2014 to January 9, 2015) by the WHO, allegedly containing the Kenya TT vaccine, tested negative for βhCG, but had exactly the same designator labels as the 3 vials obtained by the KCDA during vaccinations taking place in October of 2014 that tested positive for βhCG. The discrepancies require explanation and are addressed in the Discussion section following the Results section.

3. Results

In this section we discuss the findings from each of the listed methodologies taking them in the order just presented in the previous section.

1) Documenting the history and goals of the WHO

We found documentation connecting decades of work by the US Agency for International Development (USAID) and the United Nations, the parent organization for the WHO making reduction in world population growth, especially in regions such as Kenya, a central goal. The WHO was established in 1945 and immediately embraced the idea that “family planning”, alias population control, later referred to as “Planned Parenthood” [66] , was a necessity for “world health”. The notion that “fertility reduction” was essential dated back to Margaret Sanger’s first birth-control clinic in the US which was established in 1916 [67] and has been carried forward all the way to this present time of writing [68] .

Contemporaneous with the WHO’s initiation of research to develop anti- fertility vaccines [5] , under the leadership of Henry Kissinger a classified report was being compiled on the basis of population growth studies predating it by several decades. The Kissinger Report [69] , also known as the US National Security Study Memorandum 200 [70] , explained the geo-political and economic reasons for reducing population growth, especially in “less developed countries” (LDCs), to near zero. That report became official US policy under President Gerald Ford in 1975 and explicitly dealt with “effective family planning programs” for the purpose of “reducing fertility” in order to protect the interests of the industrialized nations, especially the US, in imported mineral resources (see p. 50 in [69] [70] ). Although the whole plan was initially withheld from the public, it was declassified in stages between 1980 and 1989. In the meantime, while that document was on its way to becoming official “policy”, the WHO research program developing “birth-control” vaccines was initiated about 1972 and presented publicly in 1976 [5] , just one year after the Kissinger Report was adopted as official policy.

The official “policy” called for “far greater efforts at fertility control” (p. 19 in [69] [70] ) world-wide, but especially in “less developed countries” (pp. 18-20 in [69] [70] ). The Kissinger Report cited documents about “Population Growth and the American Future” as well as “Population, Resources and the Environment” and targeted LDCs specifically for “fertility control”. Justifying certain LDC targets were their known reserves of aluminum, copper, iron, lead, nickel, tin, uranium, zinc, chromium, vanadium, magnesium, phosphorous, potassium, cobalt, manganese, molybdenum, tungsten, titanium, sulphur, nitrogen, petroleum, and natural gas (see p. 42 in [69] [70] ). The linking of mineral resources with population control (“family planning”) was because the industrialized nations were already having to import significant quantities of the named minerals at considerable cost and The Kissinger Report anticipated those costs were certain to rise because of instability in those LDCs precipitated by population growth (p. 41 in [69] [70] ).

The Kissinger Report also blamed population growth for pollution far in advance of the 2009 issue of the WHO Bulletin, where Bryant et al. [61] predicted a “significant increase of greenhouse gas emissions” (p. 852). That WHO publication estimated a rise in global population from around 6.8 billion people in 2009 to 9.2 billion by 2050. Extending that WHO argument, Bill Gates in 2010 expressed the hope that vaccines along with “family planning” could bring population growth to nearer to zero [71] . Whereas Bryant et al. described anti-fertility measures as “voluntary family planning services”, they acknowledged that such WHO “services” had been reported as deceiving the persons “served” (pp. 852-853, 855) with “sterilization procedures being applied without full consent of the patient” [our italics] (p. 852). Similarly, a 1992 study entitled Fertility Regulating Vaccines published by the UN and WHO Program of Research Training in Human Reproduction, reported “cases of abuse in family planning programs” dating from the 1970s including:

incentives [our italics]∙∙∙ [Such as] women being sterilized without their knowledge∙∙∙ being enrolled in trials of oral contraceptives or injectables without∙∙∙ consent∙∙∙ [and] not [being] informed of possible side-effects of∙∙∙ the intrauterine device (IUD). (p. 13 in [72] )

The authors of that WHO report said that phrases like “family planning” and “planned parenthood” were more acceptable to the public. They chose not to mention “anti-fertility measures for population control”. Nor did they think it wise to talk about “economic development” (p. 13) in mineral rich LDCs, or the assistance industrialized nations could provide in bringing those mineral resources to market. Speaking for the WHO, Bryant et al. wrote “it is perhaps more conducive to a rights-based approach to implement family planning programs [our italics] in response to the welfare needs of people and communities rather than in response to international concern for global overpopulation” (p. 853 in [61] ). The WHO public message was to be about “health” and “family planning”. However, the message of hope would occasionally include a reference to “birth-control” vaccines. For instance, on January 22, 2010 it was officially announced that the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation had committed $10 billion to help accomplish the WHO population reduction goals in part with “new vaccines” [73] [74] .

About a month later, Bill Gates suggested in his “Innovating to Zero” TED talk in Long Beach, California on February 20, 2010 that reducing world population growth could be done in part with “new vaccines” [71] . At 4 minutes and 29 seconds into the talk he says:

The world today has 6.8 billion people. That’s headed up to about 9 billion [here he is almost quoting Bryant et al.]. Now, if we do a really great job on new vaccines [our italics], health care, reproductive health services, we could lower that by, perhaps, 10 or 15 percent∙∙∙ [71]

Given the published intentions of the WHO and its collaborators concerning population growth reduction, we focus attention next on the published scientific literature from the Web of Science and PubMed about the WHO anti-fertility vaccine research programs.

2) Examining the published scientific research

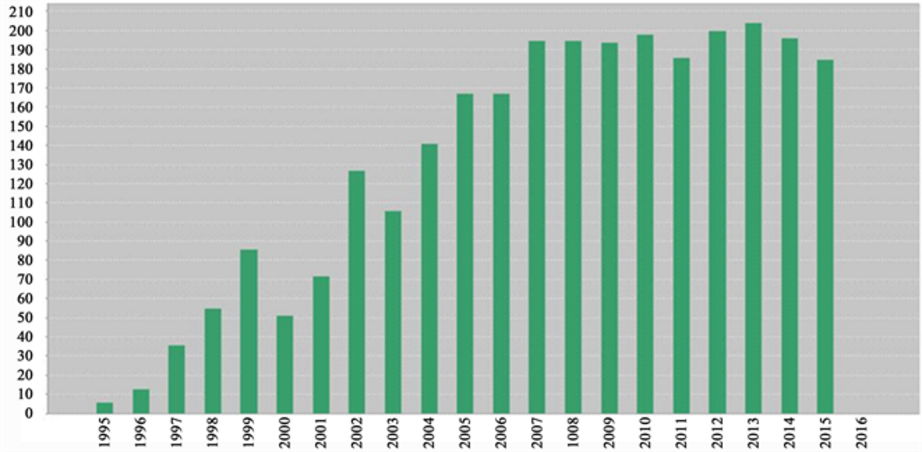

A search on the Web of Science (and PubMed) for “tetanus toxoid AND beta hCG” led to publications by WHO researchers spearheaded by G. P. Talwar [4] - [24] . After his first report appeared in 1976 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences [5] , the number of citations of the stream of publications emanating from that WHO research program would begin to grow exponentially. By August 5, 2016, the Web of Science database already pointed to 150 research publications citing the 1976 report while subsequent papers have now been cited many thousands of times. Figure 1 shows citations through 2015 of just one of the follow up papers by Talwar et al., this one from 1994 titled, “A vaccine that prevents pregnancy in women” [13] . It also appeared in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and by January 9, 2016, according to the Web of Science, had already been cited 2538 times.

We focus attention next on findings from a forensic journalism methodology laying out the chronology connecting the WHO anti-fertility research agenda to the 2013-2015 vaccination campaign in Kenya.

3) Tracking the reported events in Kenya

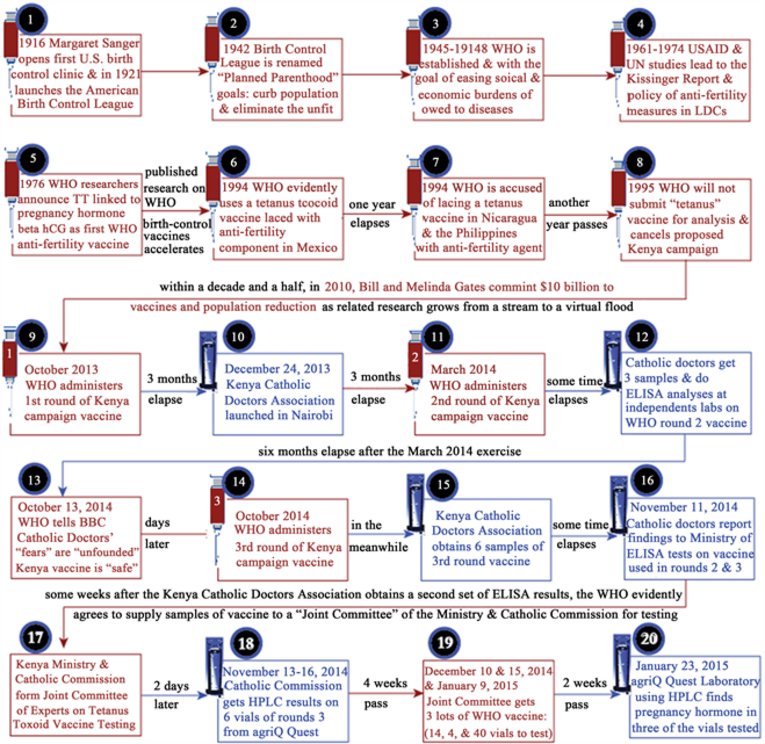

Figure 2 actually begins with milestone events leading up to and through the WHO campaign in Kenya. Event 1 in the top row represents the population reduction efforts of Margaret Sanger beginning in 1916. She described the goal to purify the “gene pool” by “eliminating the unfit”―persons with disabilities [75] . This meant establishing some means of surgical sterilization or otherwise preventing “unfit” persons from reproducing.

Figure 1. A bar graph generated from the Web of Science showing growth through 2015 in the number of citations of the 1994 paper titled “A vaccine that prevents pregnancy in women,” published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, and authored by G. P. Talwar and some of the same co-authors on the 1976 paper also in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that debuted the first human testing of a WHO anti-fertility conjugate of the beta chain of human chorionic gonadotropin with tetanus toxoid.

Figure 2. A chronology of milestone events leading up to and including the current research project based on the WHO “tetanus” campaign in Kenya 2013-2015.

By 1942, the American Birth Control League, having been publicly criticized as “anti-family” and “pro-promiscuity”―words used by Mike Wallace while interviewing Sanger on September 21, 1957 [76] ―changed its name to “Planned Parenthood” with Margaret Sanger at the helm from 1952-1959. In the period from 1945 to 1948, after World War II had ended, while the WHO was being conceptualized and becoming the first world-wide subordinate agency under the auspices of the UN, “Planned Parenthood”, headed up by Bill Gates’s father [77] , was promoting the idea that population growth, unless halted or reduced by governmental intervention, would inevitably lead to world-wide famine, disease, the destabilization of governments, and at least one more world war.

In 1961, the US Agency for International Development (USAID) joined with the UN and the WHO in population studies culminating in The Kissinger Report first promulgated as an official classified document to government officials in 1974. In the meantime, moving to the second row in Figure 2, WHO researchers led by Talwar were linking TT to βhCG and testing the first WHO contraceptive vaccine on humans [10] . Then, the years 1993, 1994, and 1995, were marked by news reports of WHO anti-fertility vaccination campaigns in LDCs?specifically, Mexico, Nicaragua and the Philippines [42] [43] [78] [79] [80] , along with a forestalled campaign in Kenya in 1995 [3] ?all of which were represented to the public in those countries, and to the vaccinated females of child-bearing age, as part of the WHO campaign to “eliminate maternal and neonatal tetanus” [56] [57] [58] [59] [60] .

As seen in Figure 2, between events 8 and 9, the $10 billion from the Gates Foundation committed in 2010 was associated by Bill Gates himself with the world-wide population control objective of the WHO to be achieved in part, according to his own words, as noted earlier, with “new vaccines” [71] . Although there is no reason to suppose that other fund-raisers, besides Gates, intended to promote the WHO population control agenda, the targeted regions for the MNT campaigns were effectively the same as the “LDCs” identified earlier in The Kissinger Report. For example, a 2015 news release by Associated Press, announced “immunization campaigns to take place in Chad, Kenya and South Sudan by the end of 2015 and contribute toward eliminating MNT in Pakistan and Sudan in 2016, saving the lives of countless mothers and their newborn babies” [81] .

From event 9 forward, news reports suggested that the WHO had represented an anti-fertility vaccine as a tetanus prophylactic [3] [31] [45] [82] . Throughout the entire chronology of events 9 - 20, the Kenya Ministry of Health and the officials speaking on behalf of the WHO, maintained that the campaign was only to “eliminate maternal and neonatal tetanus” [44] . For example, in his official statement on behalf of the Kenya government, Health Minister James Macharia told the BBC that the WHO Kenya campaign vaccine is “safe” and “certified” and he said “I would recommend my own daughter and wife to take it” [44] .

With the foregoing in mind, in Part 4, we compare the schedules for administering tetanus vaccine as contrasted with those for TT/βhCG conjugate (birth- control) vaccine, and, then, in Part 5 we present and discuss the laboratory findings analyzing samples of the vaccines from the 2013-2015 Kenya campaign as summarized in events 12 - 20 of Figure 2.

4) Comparing vaccination schedules for tetanus and anti-fertility

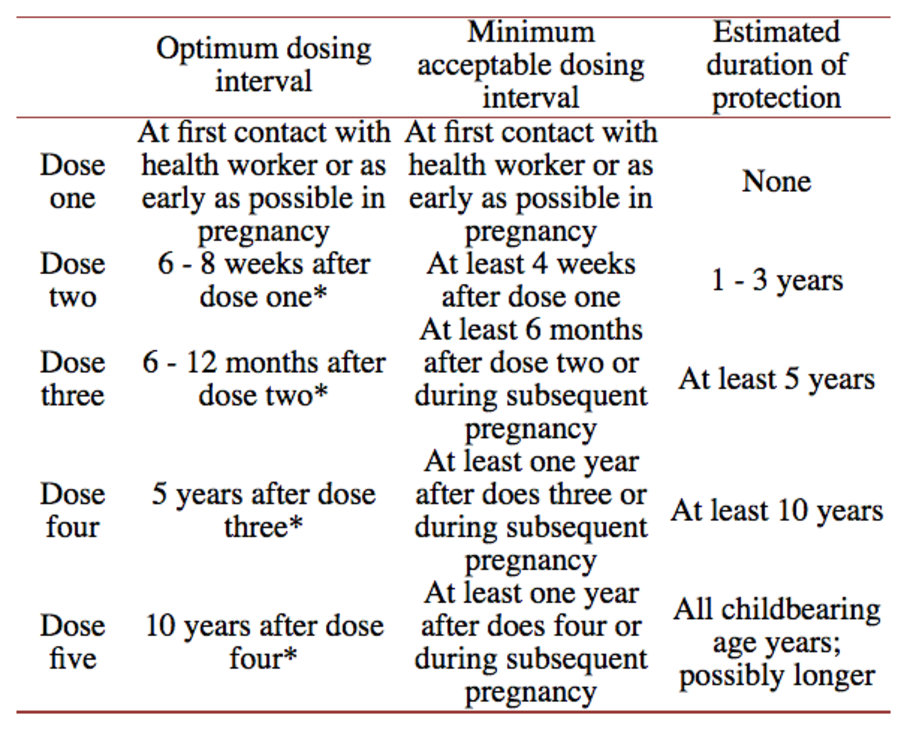

Table 1 shows the officially recommended intervals for TT shots, including those combined with other antigens such as diphtheria and pertussis [78] . Those intervals differ very little for adults and neonates. The most important difference is that in the case of an unvaccinated woman who is already pregnant, a stepped up schedule for TT is recommended with “the first dose as early as possible

Table 1. “Tetanus toxoid vaccination schedule for pregnant women and women of childbearing age who have not received previous immunisation against tetanus,” as reported in Martha H. Roper, J. H. Vandelaer, and F. L. Gasse in The Lancet 2007, 370: 1947-1959.

*Should be given several weeks before due date if given during pregnancy.

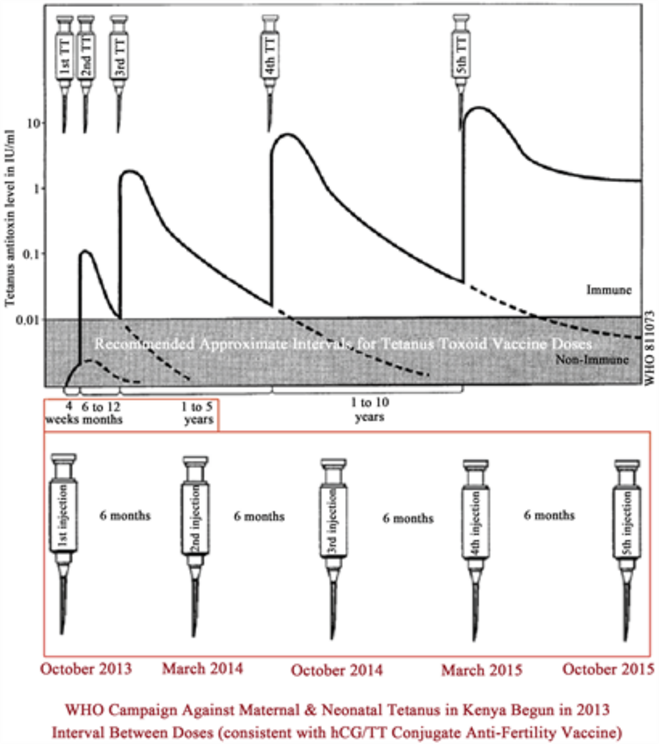

during pregnancy and the second dose at least 4 weeks later” ( [37] , p. 200). But contrary to all of the published research on TT inoculations, the WHO Kenya campaign spaced 5 doses of “TT” vaccine at 6 month intervals contravening, as illustrated in Figure 3, the repeatedly published schedule for TT. However, the Kenya schedule was identical to the one published for the WHO birth-control conjugate of TT linked to βhCG [6] [10] [26] [50] [83] . The official schedule of TT doses and the intervals between them in Table 1 were published in The Lancet in 2007 for girls and women of child-bearing age and for neonates ( [35] , p. 1951) and was unchanged from the WHO schedule published in 1993 in the document titled, The Immunological Basis for Immunization Series, Module 3: Tetanus, and as copied in the top half of Figure 3 [84] .

The critical elements of the generalized TT administered as a separate antigen (as in the WHO Kenya “tetanus” campaign protocol) are these:

a) The official dose-size consists of half a milliliter of the TT vaccine (0.5 ml).

b) The number of doses recommended to establish about 5 years’ worth of immunity requires at least 3 doses.

c) And, the approximate intervals between the first 3 doses and the “booster” doses to follow (4 more shots, or 7 shots in all) are very similar in all cases to those in the schedule for neonates.

The official documents show that the published WHO schedule for doses of TT is consistent with the “one-size fits all” CDC doctrine [35] [36] and is essentially the same for all recipients even if TT is combined with pertussis and diphtheria antigens. The same schedule published by the WHO in 1993 was copied and re-iterated in 2007 [57] [84] and calls for “three primary doses of 0.5 ml―

Figure 3. Recommended schedule for administering tetanus toxoid from A. M. Galazka (1993, p. 9, Figure 2) [84] at the top contrasted with the WHO schedule applied in the Kenya campaign. The copyright to the original figure is held by the World Health Organization but according to their published notice the containing document “may, however, be freely reviewed, abstracted, reproduced and translated, in part or in whole.”

according to the standard CDC doctrine which is contrary to dose-response theory and research in every other area of medicine [85] [86] , and one of the main explanations for the pervasiveness of auto-immune disorders associated with vaccines [87] [88] [89] [90] [91] ―one-size “fits-all” dose produced by manufacturers for all recipients at least four weeks apart, followed by booster doses at 18 months, 5 years, 10 years and 16 years and then every 10 years” [57] thereafter. The TT schedule for adolescents and adults, and the one for neonates, require the full basic course of 7 doses of vaccine as shown in Table 1 [57] and as spelled out in the top part of Figure 3 where the intervals between doses are indicated on the horizontal time line. Therefore, a question arises: Why would the WHO Kenya “tetanus” campaign require a radically different schedule of 5 doses at 6 month intervals, as shown in the bottom half of Figure 3? Interestingly, the dosing schedule for the “tetanus” campaign in Kenya 2013-2015 was exactly the one set for the WHO birth-control conjugate containing TT/βhCG [2] [9] [36] .

Figure 3 shows the intervals between doses recommended for tetanus immunization for persons who have not been previously inoculated with a tetanus vaccine series (in the top half of the figure). Note that all 5 doses of the WHO Kenya campaign (in the larger red rectangle at the bottom of Figure 3) would be administered in 30 months, as contrasted with the same time frame normally accounting for only 3 doses in the recommended TT schedule (the smaller red rectangle near the center of Figure 3). The intervals between doses in the WHO campaign in Kenya beginning in October 2013 (in the bottom half of Figure 3) are dramatically different from the generalized WHO protocol with an interval of one month between doses 1 and 2, up to 12 months between dose 2 and 3, up to five years between 3 and 4, or even 10 years between doses 4 and 5 [42] [70] [74] [75] . The protocol would be different, of course, if an individual had been previously inoculated, for instance, with the DPT (diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus) series or any other multi-valent series containing TT within the preceding 5 years, in which case, the recommended procedure would be to administer just one dose (a tetanus “booster”) not to be repeated for up to 10 years. However, as shown inside the red border in roughly the bottom half of Figure 3, the WHO Kenya campaign involved 5 doses of vaccine administered at approximately 6 month intervals over less than a 3 year period.

Moreover, the fact that no males, only females of child-bearing age, were vaccinated in the WHO Kenya campaign seems to imply that tetanospasmin produced by Clostridium tetani cannot infect post-birth males of any age, or females outside the targeted range of 12 to 49 years. The defense that the WHO intended only to target “maternal and neonatal tetanus” seems odd in view of the fact that males are about as likely as females to be exposed to the bacterium which is found in the soil everywhere there are animals. The notion that males, and females outside the child-bearing age range, are less susceptible to cuts, scrapes, and other injuries that might introduce a tetanus bacterium is not credible. But that difficulty is not the only unexplained irregularity in the WHO “tetanus” vaccination campaign in Kenya. Until after the KCCB published its suspicions and preliminary laboratory results confirming them in November 2014 [2] about the WHO “tetanus” campaign underway from October 2013, the following unusual facts made it difficult for the KCDA to obtain the needed vaccine samples for laboratory testing:

・ the campaign was initiated not from a hospital or medical center but from the New Stanley Hotel in Nairobi [92] ;

・ vials of vaccine delivered to each vaccination site for this special “campaign” were guarded by police;

・ handling of vials of vaccine by nursing staff at the site administering the shots was strictly controlled so that when a vial was used up it had to be returned to WHO officials under the watchful eyes of the police in order for the nurse to obtain a new one;

・ vials of WHO “campaign” vaccine were never stored in any of the estimated 60 local facilities but were distributed from Nairobi and used vials were returned there at considerable cost under police escort.

The fact that vials of this particular vaccine had to be stored in Nairobi is peculiar for two reasons: for one, according to the KCDA this is not usually required for vaccine distribution, and, for another, the Kenya Catholic Health Commission (as the medical branch of the KCCB) also manages a network of 448 Catholic health units consisting of 54 hospitals, 83 health centers and 311 clinical dispensaries plus more than 46 programs for Community Based Health and Orphaned and Vulnerable Children scattered all over Kenya’s 224,962 square miles [93] ―an area larger than any US state in the lower 48 except for Texas at 268,601 square miles [94] . In addition, the Catholic Health Commission manages mobile clinics for the nomadic peoples who move about Kenya and into the arid regions of bordering countries. Usually, vaccines in Kenya, according to our physician co-authors (Drs. Karanja and Ngare), would be handled by the nearest hospital, health center, or mobile clinic: why did the particular “tetanus” vaccine used in the MNT campaign of 2013-2015 require so much special handling beginning from the New Stanley Hotel in Nairobi?

In our final part, we present and discuss some of the details of the analyses of 7 vials of vaccine obtained by the KCDA directly from vials being injected in March and October of 2014 during the WHO Kenya 2013-2015vaccination campaign as well as the 52 vials eventually handed over by the WHO to the “Joint Committee of Experts” from vaccines stored in Nairobi.

5) Laboratory Analyses of the WHO vaccines

The original laboratory results of several different enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) previously referred to in various news reports (already cited) along with results from subsequent analyses using anionic exchange high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) are tabled below in this section.

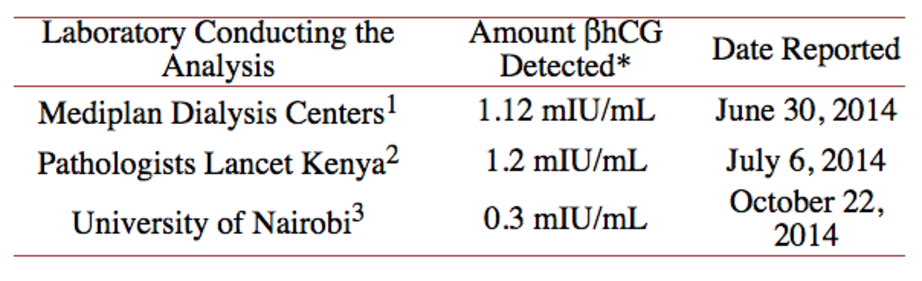

Samples of the WHO “tetanus” vaccine used at the March 2014 administration (event 11 in Figure 2) were disguised as blood serum and were subjected to the standard ELISA pregnancy testing for the presence of βhCG at three different laboratories in Nairobi (event 12 in Figure 2). Results of those analyses are presented in Table 2. Although none of the samples contained enough βhCG to surpass the threshold for a positive judgment of “pregnancy” in a blood sample, all of them tested positive for βhCG above the threshold of zero βhCG expected for a TT vaccine.

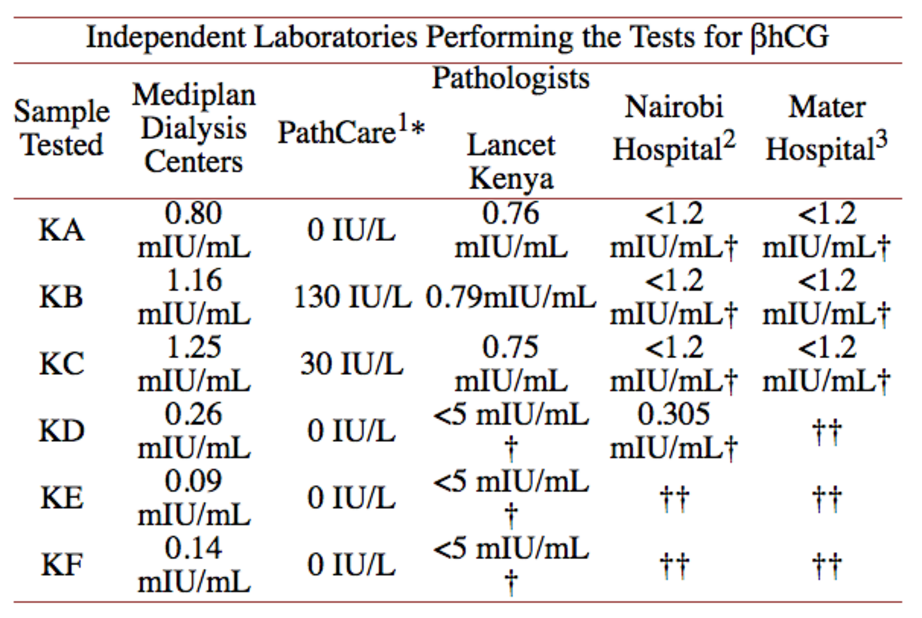

At the October 2014 round of WHO vaccinations (dose 3 for participating women shown as event 15 in Figure 2), the KCDA obtained six additional vials of the WHO “tetanus” vaccine and apportioned carefully drawn samples (aliquots) for distribution to 5 different laboratories for ELISA testing with results as shown in Table 3. All but one of the tests showed the presence of βhCG in 3 the 6 samples tested (KA, KB, and KC). Even the PathCare Laboratory, which used less sensitive ELISA kits, ones capable only of measuring international units per liter, IU/L, rather than the more sensitive ELISA kits measuring thousandths of an international unit per milliliter, mIU/ml, found quantities of βhCG in two of the samples (KB and KC) that were well above the expected zero.

Table 2. ELISA results for a sample of WHO “tetanus” vaccine obtained by the Kenya Catholic Doctors Association from the March 2014 administration.

*There is a long-standing consensus [95] [96] reflected in available ELISA kits [97] [98] that any amount < 5 mIU/mL is in the normal range for a non-pregnant woman. In the WHO vaccine samples the level of βhCGshould be zero. For the sensitivity of ELISA tests to βhCG, see [97] - [102] . 1PO Box 20707, Nairobi, ph. 0726445570, [email protected]; 28th Floor-5th Avenue Building, Ngong Road, Nairobi, ph. 0703 061 000 www.lancet.co.ke; 3College of Health Sciences, School of Medicine, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health.

Table 3. ELISA results for six samples of WHO “tetanus” vaccine obtained by the Kenya Catholic Doctors Association from the October 2014 administration (blank cells mean only that no report was returned to the KCDA).

*The Pathcare cut-off for a positive judgment for pregnancy was >4 IU/L (as also used by the Exeter Clinical Laboratory in England [100] ), which is the same as a negative judgment for <5 mIU/mL as used by the other laboratories with ELISA kits calibrated for mIU/mL with the normal range for a non-pregnant person set at <5 mIU/mL which is the equivalent standard value for the majority of ELISA kits for measuring βhCG, for a few examples see [97] - [102] . †Either the measured βhCG fell below the minimum for a positive pregnancy judgment or the laboratory reported no result implying levels of βhCG in the normal range. ††In these cells, no sample could be delivered to the laboratory because not enough fluid remained in vials KD, KE, and KF. 1Regal Plaza, Limuru, Road, PO Box 1256-00606 Nairobi, [email protected]; 2POBox 30026, G.P.O 00100, Nairobi, Tel: +254(020) 2845000, +254(020) 2846000, [email protected]; 3PO Box 30325, Nairobi, Tel: 531199 3118, no email listed on report.

With the results of Table 2 and Table 3 in hand, on November 11, 2014, the Catholic doctors took their findings to the Kenya Ministry of Health (as WHO surrogates) at an official meeting of Kenya’s “parliamentary health committee” [3] (event 16 in Figure 2). At that meeting, the Cabinet Secretary, James Macharia, rejected the ELISA test findings and expressed “trust” in the WHO and UNICEF [3] . However, the Ministry proposed a follow up by a “Joint Committee of Experts on Tetanus Toxoid Vaccine Testing” to include representatives of WHO on the one hand and the KCDA on the other (event 17 in Figure 2). The Ministry also decided to order high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) retesting the vaccines already in possession of the KCDA having been obtained during the ongoing October 2014 vaccine administration and of which samples had already been tested by ELISA (as shown in Table 3). It was agreed also that additional vials of the Kenya vaccine would be supplied by the WHO for HPLC analysis. The samples already being held by the KCDA and ones to be supplied from the government (WHO) stores were to be delivered to AgriQ Quest Laboratory in Nairobi as verified in the presence of representatives of the “Joint Committee” (including both WHO surrogates and doctors representing the KCCB). AgriQ Quest Laboratory was instructed to determine “if βhCG was present in the submitted vials” (see slide 5 in the official PowerPoint Presentation [62] ), to be reported back to the “Joint Committee” at a date to be announced later by the Ministry.

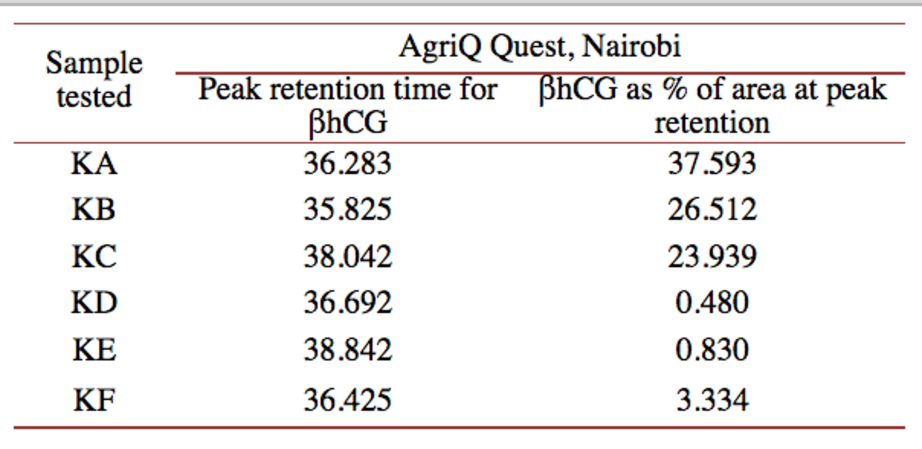

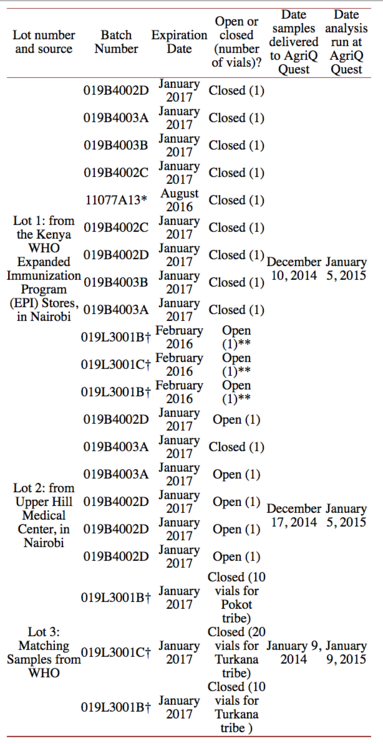

In fact, two separate sets of HPLC tests would be run by the AgriQ Quest Laboratory. The first set of results, as shown in Table 4, were reported within five days to the KCCB on November 16, 2014 in a document of public record titled Laboratory Analysis Report for the Health Commission, Kenya Conference of Catholic Bishops, Nairobi [63] (event 18 in the chronology of Figure 2). Nine weeks later, after a lapse of 58 calendar days from the time of the setting up of the “Joint Committee”, the WHO surrogates in the Kenya Ministry of Health by-passed the “Joint Committee” contravening their prior commitment and delivered an additional 40 vials of WHO vaccine directly to AgriQ Quest on January 9, 2015. Of the 52 aditional vials allegedly coming from Nairobi supplies to be subjected to HPLC analysis (event 19 in the chronology, Figure 2), the set delivered on January 9, 2015 directly to AgriQ Quest, consisted of 40 vials with the exact same Batch Numbers as the 3 vials that had formerly tested positive for βhCG. We will revisit this fact in the Discussion section below.

Table 5 summarizes results reported by AgriQ Quest to the “Joint Committee” in a document of public record titled Laboratory Analysis Report for the Joint Committee of Experts on Tetanus Toxoid Vaccine Testing [64] and in an oral presentation assisted by a PowerPoint document also of public record on

Table 4. Summary of Anionic Exchange High Pressure Liquid Chromatography testing for presence of βhCG in the six samples of WHO “tetanus” vaccine from the October 2014 administration using Detector A (220 nm).

*For all analyses, 100% of each sample was processed in 40 minutes.

Table 5. Lots delivered by the Joint Committee to AgriQ Quest for analysis with the nine digit batch number for each vial, its expiration date, whether it was closed or opened when received for analysis, and whether it contained βhCG according to the results obtained.

*This particular vial was the only one from Biological E, Ltd. All other vials were manufactured by the Serum Institute in India. **Judged by analysis to contain βhCG. †Note that the batch numbers on the vials containing βhCG are identical to “matching” vials supplied by the WHO that were tested and did not contain βhCG.

January 23, 2015 [62] 4. Altogether, 58 vials of WHO vaccine were tested. They consisted of the 6 vials previously tested by ELISA and also by HPLC at the request of the Catholic Health Commission (Table 3 and Table 4, respectively). Additionally, there were 52 new samples provided by the WHO as presented in Table 5. Table 4 shows that the first HPLC analyses, conducted at the request of the Health Commission of the KCCB, using the same 6 samples of WHO “tetanus” vaccine from the October 2014 (round 3 administration by the WHO) confirmed the ELISA findings as reported earlier in Table 3. Samples KA, KB, and KC contained βhCG.

The analyses summed up in Table 5, from the second series of HPLC tests, called for by the “Joint Committee”, was run a few weeks after those reported in Table 4. Reading left to right across the rows in Table 5, the sample vials of vaccine are listed by Batch Number, Expiration Date, whether the vial was found to have been Open or Closed upon delivery to AgriQ Quest, the date delivered to AgriQ Quest, and, finally, the date when the analysis was run. Proceeding directly to the question of interest, the 3 vials of the 6 obtained by the Catholic doctors from the WHO vaccine actually used in the October round of injections, the same vials of which samples previously tested positive for βhCG by multiple ELISA analyses and by the HPLC analyses summed up in Table 4, were again found to contain βhCG. They are marked with a double asterisk (**) in the fourth column from the left in Table 5.

By contrast, all 52 additional vials of vaccine delivered to AgriQ Quest by the WHO tested negative for βhCG. More importantly, as noted above, of the 40 samples provided directly to AgriQ Quest by the WHO surrogates on January 9, 2015, the only ones that had the same identifying Batch Numbers as ones containing βhCG from the October 2014 administration, also tested negative for βhCG The reports to the “Joint Committee” on January 23, 2015 [62] [64] by AgriQ Quest (event 20, Figure 2) concluded that only 3 of the 6 vials obtained directly by the Catholic doctors at the round 3 administration in October 2014 contained βhCG (namely those numbered 019L3001B or 019L3001C).

4. Discussion

Given the foregoing results, the following facts are known and require explanation:

・ The WHO has been seeking to engineer antifertility vaccines since the early 1970s [5] .

・ Reducing global population growth, especially in LDCs, through antifertility measures has long been declared a central goal of USAID/UN/WHO “family planning” [66] - [77] .

・ Spokespersons associated with the Catholic Church and pro-life groups have published suspicions at least since the early 1990s that the WHO was misrepresenting clinical trials of one or more antifertility campaigns as part of the world-wide WHO project to “eliminate maternal and neonatal tetanus” [3] [41] [42] [43] [45] [92] [103] [104] [105] [106] .

・ Comparison of the published schedules for TT versus TT/hCG conjugate found the WHO dosage plan in the Kenya 2013-2015 campaign to be incongruent with any of those for TT but congruent with published schedules used in TT/hCG research [this paper].

・ Multiple analyses of samples of WHO “tetanus” vaccines, alleged by one or more Catholic spokespersons to have been obtained from vials actually being administered by WHO officials as “tetanus” prophylactics, were found to contain hCG [1] [2] [43] [45] [103] [104] [105] [106] .

・ As recounted in this paper, documents in the public record show that half the vials taken from actual administrations of WHO vaccine during the Kenya campaign in 2014, ones supposedly aimed to prevent MNT, tested positive for βhCG [2] [63] [64] .

An important component of the present investigative research is the discovery of βhCG in some of the vaccine vials used in the WHO campaign in Kenya supposedly aiming to prevent MNT. Possible explanations for the finding of βhCG in those vials include contamination by one or more accidents that might include: 1) a manufacturer’s error in production or labelling; 2) unreliable analysis by the Nairobi laboratories (owing to unclean wells, tubes, gloves, pipette tips, expired or damaged ELISA kits, or poorly calibrated HPLC equipment, inadequately trained laboratory personnel, faulty handling of samples received, mixing of samples, and so on); 3) careless or otherwise inaccurate reporting, or the contaminating βhCG might have been deliberately added by the KCDA seeking to sabotage the WHO anti-fertility efforts by making up false stories about the ongoing “eliminate MNT” project.

Noting immediately that we are relying on reasonable inference to reach the conclusion that we offer at the end of this paper as our opinion, we believe that some of the competing alternatives can be ruled out to narrow the field of possibilities. To begin with, a manufacturing error accidentally getting βhCG in just 3 vials but missing 40 vials from the very same “batch” as judged by the Batch Number is unlikely. Similarly, labeling errors marking just 3 vials containing βhCG with the same label associated with 40 vials not containing βhCG is equally unlikely for the same reason. Batch Numbers are used to track whole lots of vaccines produced on a given run from the same vat of materials in a liquid mixture. Coordinated manufacturing and labeling errors repeated 43 times, 21 times for label 019L3001C and 22 times for 019L3001B, could not be expected to occur by chance but only by intentional design.

Next, there is the possibility of unreliability of handling by laboratory personnel, faulty kits or equipment, and the like. But any explanation attributable to somewhat randomized (unintentional) errors can only account for stochastic variability, e.g., differences across samples of the same vials of vaccine as tested at different laboratories (Table 2 and Table 3) or at different times in the same laboratory (Table 4 and Table 5). However, the myriad sources of unreliability can all be definitively ruled out when the same results for the 6 vials tested repeatedly and independently on different occasions and by different laboratories with more than one procedure give the same pattern of outcomes. In the latter instance, the one at hand, in this paper, we have what measurement specialists call successful triangulation where multiple independent observations by multiple independent observers using multiple procedures of observation concur on a single outcome. In such an instance, all the possible sources of unreliability can be dismissed and we are left only with some non-chance alternatives.

Among the non-chance alternatives we come to the possibility that the KCDA salted the samples of vaccine that tested positive for βhCG. Logically that possibility is inconsistent with the fact that the KCDA had the opportunity to salt the vials and samples for all the ELISA tests and for all 6 of the vials they handed over twice for testing to AgriQ Quest (Table 4 and Table 5). Also, even if the KCDA had access to βhCG so as to add it to just the vials that would test positive for it, such a deliberate mixture before handing samples over to the laboratories for testing would not produce the chemical conjugate found according to AgriQ Quest in the samples that tested positive by HPLC. In their oral report to the “Joint Committee” they described the βhCG they found in those 3 vials as “chemically linked” (on slide 11 of [62] . Such linking is consistent with the patented process for TT/hCG conjugation as described by Talwar [5] [84] , but could not be achieved by simply mixing βhCG into a vial of TT vaccine.

Published works by the WHO and its collaborators continue to encourage and/or sponsor research to generate antibodies to βhCG through “a recombinant vaccine, which would: 1) ensure that the “carrier” is linked to the hormonal subunit at a defined position and 2) be amenable to industrial production” [23] . Such a conjugate has already been achieved with a bacterial toxin (from E. Coli) and can be mass produced with the assistance of a yeast (Pischia pastoris). Also, a DNA version of the new conjugate has already been approved for human use by the United States Food and Drug Administration and has already been used with human volunteers [9] [12] [13] [14] [18] [21] [22] [27] [28] , and WHO’s lead researcher has already claimed success in producing a vaccine against βhCG enhanced with recombinant DNA [17] [21] [22] [23] [24] [107] .

Finally, there is one other reported experimental study that merits mention. One of our anonymous reviewers for a draft version of this paper suggested a host of follow up studies that might be done with the help of recipients of 1 - 5 doses of the Kenya vaccine. One was to measure βhCG antibodies in the blood serum of vaccine recipients downstream from the exposure. If a significant proportion of Kenyan women who received one or more of the WHO “tetanus” injections tested positive for βhCG antibodies, such a result would show that they received βhCG “chemically linked” to some “carrier” pathogen such as TT [108] . This follows because TT by itself would not engender production of βhCG antibodies. Perhaps such a study may be underway in Kenya, or will be done in the future, but the present team of authors lacks the resources to do it. However, such a study from women participants in the WHO “tetanus” vaccination campaign in the Philippines 1993 was already done. J. R. Miller reported that pro-life groups in the Philippines tested the blood sera of 30 of the estimated 3.4 million women vaccinated by WHO in that “tetanus” campaign and 26 of them tested positive for “hCG antibodies” [106] [109] .

5. Conclusion

Laboratory testing of the TT vaccine used in the WHO Kenya campaign 2013- 2015 showed that some of the vials contained a TT/βhCG conjugate consistent with the WHO’s goal to develop one or more anti-fertility vaccines to reduce the rate of population growth, especially in targeted LDCs such as Kenya. While it is impossible to be certain how the βhCG got into the Kenya vaccine vials testing positive for it, the WHO’s deep history of research on antifertility vaccines conjugating βhCG with TT (and other pathogens), in our opinion, makes the WHO itself the most plausible source of the βhCG conjugate found in samples of “tetanus” vaccine being used in Kenya in 2014. Moreover, given that all vaccine manufacturers and vaccine testing laboratories must be WHO certified, their responsibility for whatever has happened in the Kenyan immunization program can hardly be overemphasized.

Funding

Co-authors Felicia M. Clement, Jaimie Ryan Pillette received funding as Ronald E. McNair Research Scholars at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette under US Office of Education Public Grant Award, and Professor John W. Oller, Jr. received a stipend from the same source for serving as their mentor during the semester of their grant (spring 2015) and was partly supported in this work by his endowed position as the Doris B. Hawthorne/LEQSF Professor III at the University of Louisiana.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

The conceptualization of this paper began in January 2015 by the first author in collaboration with Felicia M. Clement and Jaimie Ryan Pillette who jointly presented a preliminary summary of some of the ideas that have been further developed in multiple versions up to the present paper. Drs. Shaw and Tomljenovic agreed to join in the work in May, 2015, writing and rewriting and helping to develop a comprehensive reference list early in the project. In November 2015 we invited the Kenyan medical doctors, Dr. Ngare and Dr. Karanja, to join us and share data they had collected during the World Health Organization 2013- 2015 campaign in Kenya. The bulk of the writing has been done by Oller with edits ranging throughout the development of the manuscript and reported findings by Shaw and Tomljenovic. Drs. Ngare and Karanja contributed data seen in the tables plus detailed explanations about how the data were collected, why certain procedures were followed, and so forth. They also brought a wealth of experience as principals in the Kenya Catholic Doctors Association. As practicing physicians they have been engaged as “boots on the ground” in many parts of the still unfolding narrative reported in this paper. Ms. Clement and Ms. Pillette were involved in the construction of the first draft of the paper and have been included in all of the editorial work through multiple drafts shared between all of the contributors. They are responsible for some of the background information on the programs of the World Health Organization. They were interested in part by the discovery that the infamous Tuskegee syphilis experiment that took place in the US from 1932 until 1972 ended in the very year that research on the WHO antifertility vaccines for “family planning” in LDCs was initiated. All authors have accepted responsibility for the content of this manuscript. Any errors remaining are ours alone.

Authors’ Information

Author affiliations are mentioned on the title page of the paper.

Datasets

The data referred to in tables in this paper, and the technical reports from which those data are extracted (specifically including those provided to the “Joint Committee of Experts on Tetanus Toxoid Vaccine Testing” referred to in the text) are available upon request from the first author at [email protected].

Cite this paper

Oller Jr., J.W., Shaw, C.A., Tomljenovic, L., Karanja, S.K., Ngare, W., Clement, F.M. and Pillette, J.R. (2017) HCG Found in WHO Tetanus Vaccine in Kenya Raises Concern in the Developing World. Open Access Library Journal, 4: e3937. https://doi.org/10.4236/oalib.1103937

References & notes at source link below.