Electric cars and child labor: how a solution to one problem can lead to the creation of another

With the growing concern on the effects of gas emissions on the environment and the active role various countries have taken in decreasing the world’s dependence on fossil fuels, an increase in demand for vehicles that use less of the once and still coveted resource have sky-rocketed in the past years. People’s preference for electric and hybrid cars have in one way, started to decrease the demand for the oil derivatives that fuel their commutes but unknowingly, started a demand for other materials.

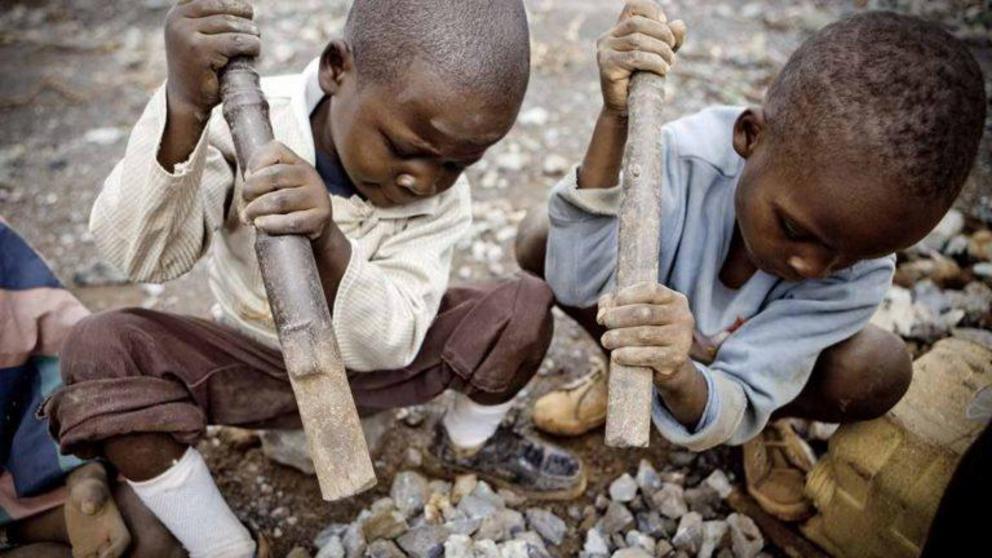

The increased demand for electric vehicles is fuelling a boom in mined metals production, both in large-scale operations as well as in small-scale operations like the ones found in the Democratic Republic of Congo. This spike in demand has already tripled the value for Cobalt, an integral component for the alternative vehicle’s power source, consequently increasing competition for the scarce material among mining operators that also include artisanal mines which employ children as laborers.

Production from these backyard mines has risen by at least half in 2017 and according to Gecamines, a state-run mining company, were responsible for almost 25% of the Congo’s total production last year. This figure is much more concerning after the fact that 65% of the world’s supply of Cobalt comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Crackdowns on operators that resorted to unethical methods such as child employment and exploitation have cost tech industry goliaths such as Apple Inc. and Microsoft Corp. bad publicity following reports that minors were being used to hand-dig the sought after ore from Congolese mines; a major concern for companies such as Tesla Inc. and Volkswagen AG who seek to find long-term supplies of the metal.

Despite the tighter restrictions on mining practices that have decreased cobalt production in 2016, a rebound in shipments of a refined derivative called cobalt hydroxide was observed in 2017, mostly coming from small and medium scale industrial producers who mix artisanal cobalt together with their own supply for export. In addition to this, reports of smuggling of the valuable ore worth billions of dollars have surfaced, estimated at about 20,000-30,000 tons a year via Zambia. These illegal exports are not declared to Congo’s agencies but are estimated to be worth as much as $2.5 billion at current pricing.

It is also estimated that, in 2017, the Congo’s exports for backyard cobalt is at 10,000 to 20,000 tons, and together with these estimates, incidents of child-labor operations may also be on the rise. The only way to really reap the benefits of cobalt is to stop the operations of these illegal mines.