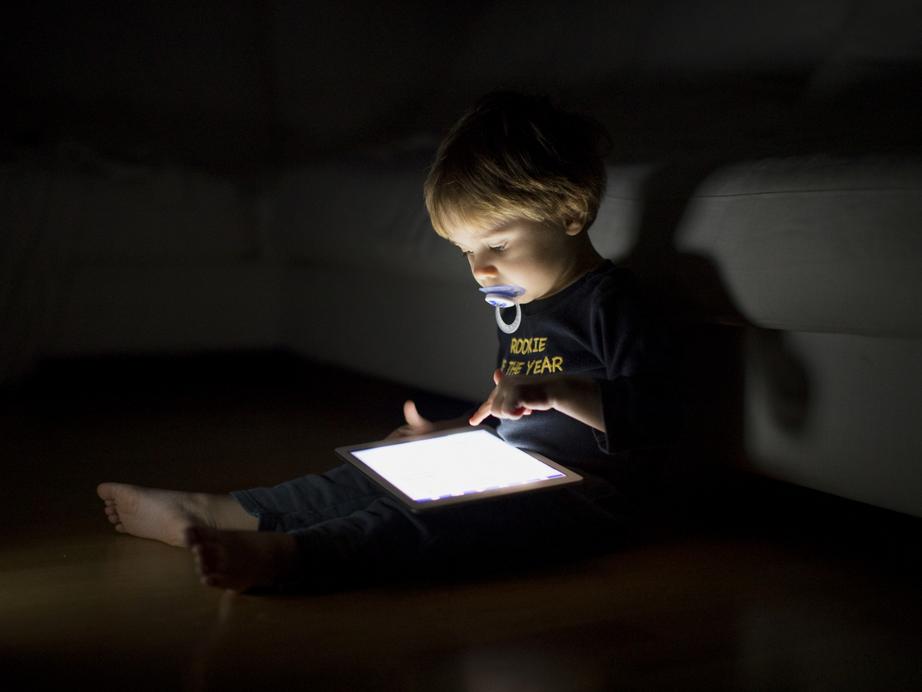

More than 80 percent of children have an online presence by the age of two

Sharenting

A toddler with birthday cake smeared across his face, grins delightedly at his mother. Minutes later, the image appears on Facebook. A not uncommon scenario – 42% of UK parents share photos of their children online with half of these parents sharing photos at least once a month.

Welcome to the world of “sharenting” – where more than 80% of children are said to have an online presence by the age of two. This is a world where the average parent shares almost 1,500 images of their child online before their fifth birthday.

But while a recent report from OFCOM confirms many parents do share images of their children online, the report also indicates that more than half (56%) of parents don’t. Most of these non-sharenting parents (87%) actively choose not to do so to protect their children’s private lives.

Over Sharing

Parents often have good reasons for sharenting. It allows them to find and share parenting advice, to obtain emotional and practical support, and to maintain contact with relatives and friends.

Increasingly, though, concerns are being raised about “oversharenting” – when parents share too much, or, share inappropriate information. Sharenting can result in the identification of a child’s home, childcare or play location or the disclosure of identifying information which could pose risks to the child.

While many sharenters says they are conscious of the potential impact of their actions, and they consider their children’s views before sharenting, a recent House of Lords report on the matter suggests not all parents do. The “growing up with the internet” report reveals some parents share information they know will embarrass their children – and some never consider their children’s interests before they post.

A recent survey for CBBC Newsround also warns that a quarter of children who’ve had their photographs sharented have been embarrassed or worried by these actions.

Think of the Kids

Police in France and Germany have taken concrete steps to address sharenting concerns. They have posted Facebook warnings, telling parents of the dangers of sharenting, and stressing the importance of protecting children’s private lives.

Back in the UK, some academics have suggested the government should educate parents to ensure they understand the importance of protecting their child’s digital identity. But should the “nanny state” really be interfering in family life by telling parents how and when they can share their children’s information?

It’s clearly a tricky area to regulate, but it could be that the government’s recently published data protection bill may provide at least a partial answer.

In its 2017 manifesto, the Conservative party pledged to:

Give people new rights to ensure they are in control of their own data, including the ability to require major social media platforms to delete information.

In the recent Queen’s Speech, the government confirmed its commitment to reforming data protection law. And in August, it published a statement of intent providing more detail of its proposed reforms. In relation to the so-called “right to be forgotten” or “right to erasure”, the government states that:

Individuals will be able to ask for their personal data to be erased.

Users will also be able to ask social media platforms to delete information they posted during their childhood. In certain circumstances, social media companies will be required to delete any or all of a user’s posts. The statement explains:

For example, a post on social media made as a child would normally be deleted upon request, subject to very narrow exemptions.

The primary purpose of the data protection bill is to bring the new EU General Data Protection Regulation into UK law. This is to ensure UK law continues to accord with European data protection law post-Brexit – which is essential if UK companies are to continue to trade with their European counterparts.

It could also provide a solution for children whose parents like to sharent, because the new laws specify that an individual or organisation must obtain explicit consent or have some other legitimate basis to share an individual’s personal data. In real terms, this means that before a parent shares their child’s information online they should ask whether the child agrees.

Of course, this doesn’t mean parents are suddenly going to start asking for their children’s consent to sharent. But if a parent doesn’t obtain their child’s consent, or the child decides in the future that they are no longer happy for that sharented information to be online, the bill also provides another possible solution. Children could use the “right to erasure” to ask for social network providers and other websites to remove sharented information. Not perhaps a perfect answer, but for now it’s one way to put a stop to those embarrassing mugshots ending up in cyberspace for years to come.