Everything you want to know about Lyme disease

Lyme disease is more common in northern areas of the United States than other regions due to the presence of animals that ticks like to feed upon.

Lyme disease is more common in northern areas of the United States than other regions due to the presence of animals that ticks like to feed upon.

What symptoms you should look for and what places are you more likely to contract it?

You may want to be a bit more wary when walking in the woods this summer. The mild winter and other indicators may mean more of the tiny ticks that carry Lyme disease. But don’t allow the terror of ticks keep you from the great outdoors.

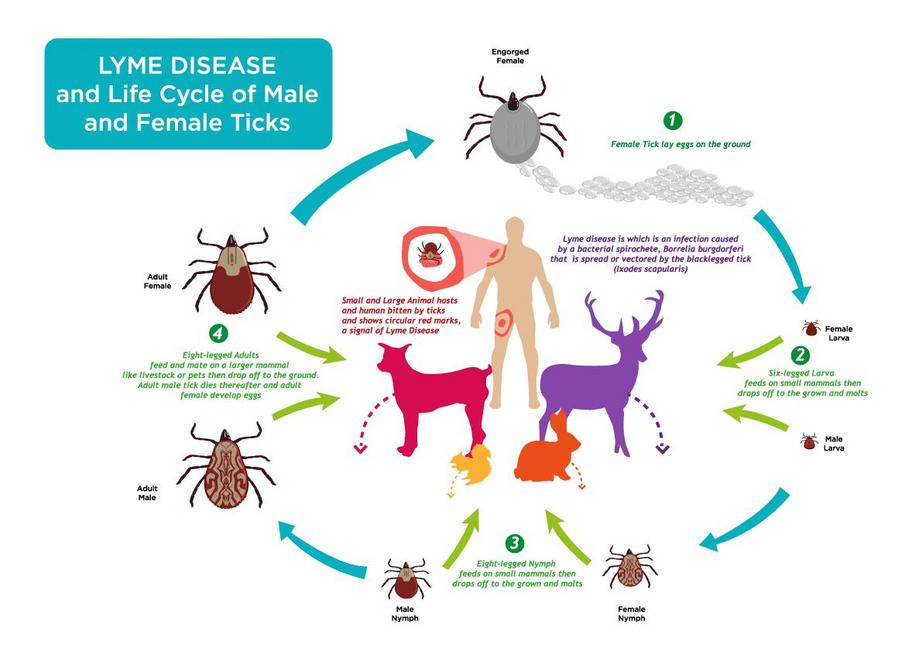

Lyme disease — so named because it was first reported in the United States in the town of Old Lyme, Connecticut, in 1975 — is caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi. It is spread by the bite of infected blacklegged ticks (also known as deer ticks) in New England, Mid-Atlantic and Great Lakes regions. It can also be spread by the western blacklegged tick in the Pacific Northwest.

While the number of Lyme disease cases is growing, it remains a largely regional concern. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 95 percent of Lyme disease cases were reported from 14 states: Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, Virginia and Wisconsin.

"Typically, Lyme disease is not acquired in the southeastern United States and central Texas," says Dr. Paul Auwaerter, an associate professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine who also serves as the clinical director for the Division of Infectious Diseases.

Lyme disease is more common in northern states because of large numbers of the deer tick's preferred hosts: white-footed mice and deer, according to the American Lyme Disease Foundation. White-footed mice are the principal "reservoirs of infection" on which many larval and ticks feed, according to the group's website.

While they may transmit other diseases, ticks common in other parts of the country — such as the Lone Star tick (Amblyomma americanum), the American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis), the Rocky Mountain wood tick (Dermacentor andersoni) and the brown dog tick (Rhipicephalus sanguineus) — are not known to transmit Lyme disease, according to the CDC.

But even finding the right tick — or wrong tick, depending on your point of view — latched onto your skin doesn't mean you're going to get Lyme disease.

"If you get the tick off within 24 to 36 hours, you're not going to get Lyme disease," says Dr. Michael Zimring, co-author of "Healthy Travel" and director of the Center for Wilderness and Travel Medicine at Mercy Medical Center in Baltimore.

The role of the mouse

White-footed mice infect up to 95 percent of ticks that feed on them.

White-footed mice infect up to 95 percent of ticks that feed on them.

New York ecologists Rick Ostfeld and Felicia Keesing have been studying Lyme disease for more than two decades. They are able to predict how many cases there will be each year by counting the mice the year before.

That's because mice are very efficient transmitters of the disease and infect the majority of ticks carrying Lyme in the Northeast. They infect as many as 95 percent of ticks that feed on them.

"An individual mouse might have 50, 60, even 100 ticks covering its ears and face," Ostfeld tells NPR. "We're anticipating 2017 to be a particularly risky year for Lyme."

That's in the Northeast, at least. So far, early surges in tick activity have been reported in areas as diverse as Michigan and California. Areas where the winter has been mild and mice population is high will likely experience a risky summer for Lyme disease.

But regional predictions aren't as important as realizing that if you're in one of those 14 states where Lyme disease is endemic, take precautions.

“There’s always a huge risk,” Dr. John Aucott, director of the Johns Hopkins Rheumatology Lyme Disease Research Center, told the Huffington Post. “It’s not like a risk of a tornado, where the tornado is either there or not.”

Lyme disease symptoms and when to worry

Only certain ticks, like the deer tick pictured here, will transmit Lyme disease to humans.

Only certain ticks, like the deer tick pictured here, will transmit Lyme disease to humans.

How can you tell how long the tick has been there? Is it full of blood?

"If the tick is flat — chances are you didn't get Lyme disease," says Auwaerter.

The telltale symptom of Lyme disease is a red, circular "bulls-eye" rash that appears five to 14 days after infection. About 70 to 80 percent of people infected develop the rash, but Dr. Steven Soloway, a board-certified rheumatologist in Vineland, New Jersey, says the numbers may be higher and many people simply don't notice the rash. Other symptoms in this first stage of Lyme disease include fatigue, chills, fever, headache, muscle and joint aches and swollen lymph nodes.

The symptoms will fade, even if untreated. Symptoms of stage 2 Lyme disease, also known as early disseminated Lyme disease, include swollen joints, particularly the knees. The symptoms are similar to rheumatoid arthritis. The difference, Soloway says, is that rheumatoid arthritis typically affects knuckles first.

Other symptoms include Bell's palsy and heart palpitations and dizziness due to changes in heartbeat.

Lyme disease is treated with antibiotics for two to four weeks. The vast majority of patients recover quickly, experts say. A very few people treated for Lyme disease will continue to have some symptoms. The cause of post-Lyme disease syndrome isn't known. But treatment, experts say, should target the specific symptoms, say joint swelling. Long-term use of IV antibiotics is not appropriate, experts say.

You can take steps to prevent Lyme disease by taking steps to avoid a tick bite. Avoid bushy and grassy areas when walking in the woods, especially in the areas with deer ticks. Wear long pants and long-sleeved shirts and wear insect repellent containing DEET on exposed skin. After walking in wooded areas, thoroughly check the skin for the poppy seed-sized ticks.

Editor's note: This story was originally published in May 2012 and has been updated with new information.