A bizarre find: tiny powerhouses in your cells run at 122 degrees

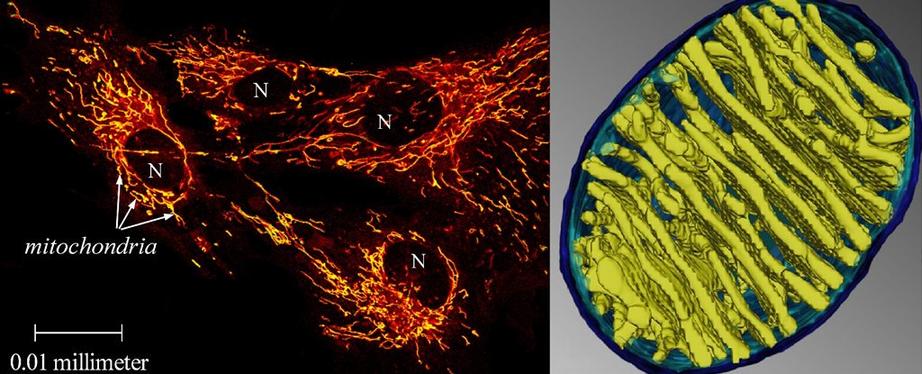

Left: Mitochondria in human cells illuminated by thermal dye, with cell nuclei marked “N.” Right: Closely juxtaposed membranes, like the fins of a radiator, could heat the mitochondrial interior.

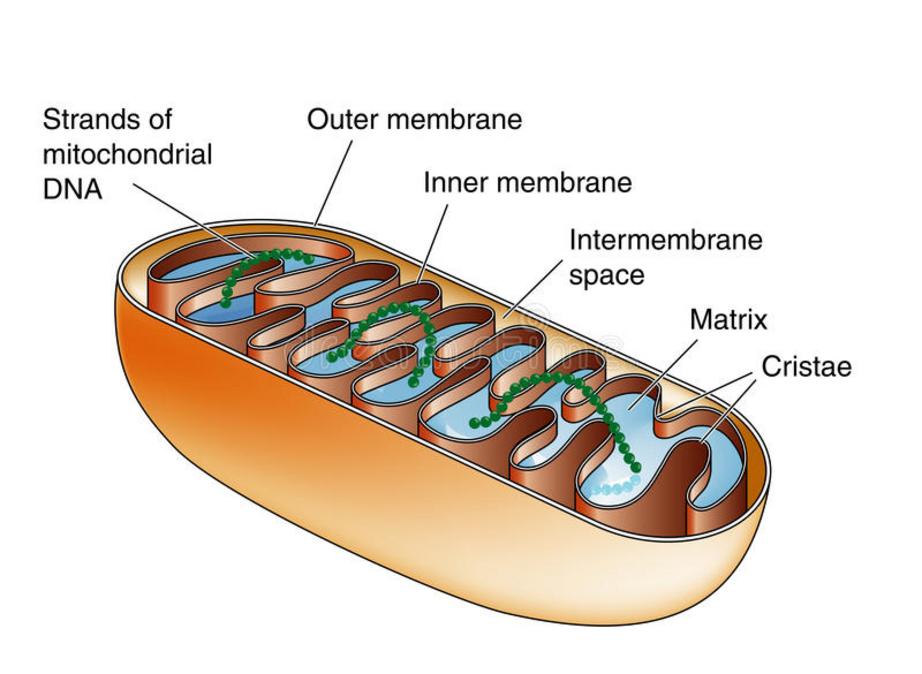

Your body is hot. Depending on the time of day, and where the thermometer is placed, it runs somewhere between 35 to 38 degrees Celsius, or 95 to 100 degrees Fahrenheit. Little organs called mitochondria, slotted into your cells like batteries in a TV clicker, produce most of this body heat. Mitochondria are the powerhouses of the cell, as biologist Philip Siekevitz called them in 1957. They use oxygen and nutrients to create energy and heat.

We feel the heat of mitochondria in every warm embrace. In every hot breath. Yet as important as mitochondria are, some of their characteristics remain unknown: For instance, how hot do these microscopic powerhouses get?

That is a difficult question to answer. But Pierre Rustin, who studies mitochondrial diseases at the French research organization INSERM, and his colleagues say they have a measurement. The researchers, using a dye sensitive to changes in temperature, gauged active mitochondria at 50 degrees Celsius. (That's 122 degrees Fahrenheit, equal to the hottest temperature ever recorded in Phoenix.)

The researchers grew human kidney cells and skin cells in petri dishes, which they kept at 38 degrees Celsius. Into these cells the scientists inserted a new type of fluorescent dye, which brightens as it cools. When the mitochondria became active, the fluorescence dimmed. This indicated that the temperature within the mitochondria rose between seven and 12 degrees Celsius, or an average of 10 degrees, as reported in the journal PLOS Biology on Thursday.

“It took us about two years of continuous work to convince ourselves and to make our results public in a scientific journal,” he said. They spent those years examining and crossing off other factors for the change in fluorescence, such as pH, cell concentration and the voltage across cellular membranes.

“It's a good paper and it's good work, but they can't control for everything,” said Nick Lane, a biochemist at University College London who was not involved with this work. Lane, in an accompanying commentary also published by PLOS Biology, said 50-degree mitochondria is a “radical claim.”

The dye responds to heat, but it may also be affected by motion. There is a “hinge region that flaps about” in the dye, Lane said, and it is possible that a more quickly flapping hinge triggered the dimming. “There is a difference between heat and molecular motion but I don't know that if that dye would necessarily tell the difference,” he said.

“It's not news that mitochondria in mammalian cells generate heat,” said Thomas Fox, a microbiologist at Cornell University who has studied mitochondria in yeasts. He said he would like to see what the dye measures in mitochondria in organisms that do not regulate body temperature like we do, such as yeast, fruit flies or worms. “Presumably that’s for follow-up studies by these authors or others,” he said.

Previous calculations suggested that there were temperature differences between mitochondria and the rest of the cell, but this gradient was tiny: just one hundred-thousandth of a degree Celsius. Rustin said these approximations were “essentially based on a much too reductive modeling of what is the structure of a mitochondrion.” Mitochondria are filled with tight rows of membranes, like the fins of a radiator. But mathematical models reduced a mitochondrion to “a sphere without internal structure,” he said.

Lane said he suspects the true mitochondrial temperature is somewhat cooler than the dye measurement. “I doubt that the 10 degree Celsius temperature difference should be taken literally,” he wrote in the accompanying article. “But it should be taken seriously.” The “obsession with genes” and genomics, as he told The Washington Post, has made conventional physiological approaches to factors like temperature less fashionable.

Rustin agreed that temperature has been largely underrated. “To further reinforce the conclusions drawn from our observations, we would need measurements using independent methods to quantify the temperature without using the fluorescence of molecules.” But these independent methods, he pointed out, do not yet exist.