Hybrid war can wreak havoc across West Africa

To continue with analyzing the countries around Nigeria’s periphery, it’s now time to turn the research’s focus over to Cameroon, one of the most stable and relatively prosperous countries in all of Africa. Despite being home to more than 240 separate ethno-linguistic groups, Cameroon avoided the destructive tribal violence of its continental peers owing mostly to its strong leadership and diversified economy. President Paul Biya, in office since 1982, has been instrumental in guiding the country through the post-Cold War transitional phase and imprinting a unified identity on its people, though the inevitable passing or retirement of this elderly politician will indeed be a pivotal moment in the country’s history that could augur negatively for its future if it’s not handled with care and finesse. If the military and security services divisively compete with one another or start promoting localized (tribal/ethnic) interests at the expense of national unity during this vulnerable transitional time, then Cameroon dangerously runs the risk of turning into another version of the Congo as it descends into multisided civil warfare.

On the other hand, Cameroon also has very promising potential in functioning as the transregional zipper state in linking together Western and Central Africa, ergo its decisive incorporation in China’s Cameroon-Chad-Sudan (CCS) Silk Road plans for building a cross-African railroad between these three states. It’s for these dual reasons why Cameroon is so important for observers to pay attention to, since it can either have a very positive future or an extremely dismal one, with it seeming unlikely that any ‘middle ground’ could be achieved given the extreme of its situation which will be discussed later on. Moreover, on an interesting ‘civilizational’ note, Cameroon is a majority Christian country with a geographically distinct Muslim minority, which while presenting certain inherent domestic challenges for national unity, could also serve as an intangible benefit in heightening the country’s regional position if it can successfully continue to balance between these elements and use them as stepping stones for more solidly integrating with its neighbors. However, due to its location, Cameroon is also very susceptible to “Weapons of Mass Migration”, which is a threat that the security services must be prepared to deal with in the event that the regional situation disturbingly spirals out of control.

The order of research is such that it begins by discussing Cameroon’s New Silk Road connectivity and the various infrastructure projects presently underway or planned for the country. After laying out the geo-economic importance of the state, the work then proceeds to examining its most pressing domestic difficulties in being between the Salafist Boko Haram terrorists and the nearby Biafran separatists, with the latter having the potential to link up with “Southern Cameroons” insurgents to recreate the Nigerian template of North-South/Muslim-Christian anti-state destabilization within Cameroon itself. Finally, the last thing that will be discussed is how Cameroon could be thrown into turmoil by “Weapons of Mass Migration”, especially those coming from its southern and eastern peripheries.

Cameroonian Connectivity

Cameroon’s geopolitical location endows it with the inherent possibility of one day functioning as the West-Central African ‘zipper’ in connecting these two neighboring regions. Part of the country obviously abuts the densely populated and economically productive region of Southern Nigeria, while also interestingly snaking northwards up to the Chadian border, from where China’s CCS railroad is envisaged to connect it across the Sahara to Chad and thenceforth to Sudan’s Red Sea coast. While the project appears to have been stalled since its 2014 announcement and its exact route through Cameroon and Chad has yet to be officially delineated, it’s known that it will at the very least terminate at the Atlantic Port of Douala and run through the Chadian capital of N’Djamena. It would make economic and structural sense for it to be built as parallel as possible to the already existing Cameroon-Chad oil pipeline, which in that case would take the route near or through the Cameroonian capital of Yaoundé and through southern Chad, evading for the most part the North and Far North regions of Cameroon (which are presently the ones threatened the most by Boko Haram).

What’s important to note about the CCS Silk Road and the Cameroon-Chad pipeline is that they terminate at different ports, with the former ending at Douala while the latter stops at Kribi. The first one of the two is the country’s largest port at the moment and also the biggest one in all of Central Africa, while the latter is being built by the Chinese as Cameroon’s only deep-water port and is planned to have an accompanying industrial zone too. It would be wisest if both of these ports were connected in some way in order to maximize their New Silk Road positions, which is exactly what several projects plan to do. The first one of relevance is the Douala-Yaoundé non-stop railroad that launched in 2014, while the second one is the proposed Kribi- Yaoundé highway. Both of these projects intersect in the national capital, from where they can then branch out to Chad or the Central African Republic, as per the Douala-N’Djamena and Douala-Bangui Corridor proposals.

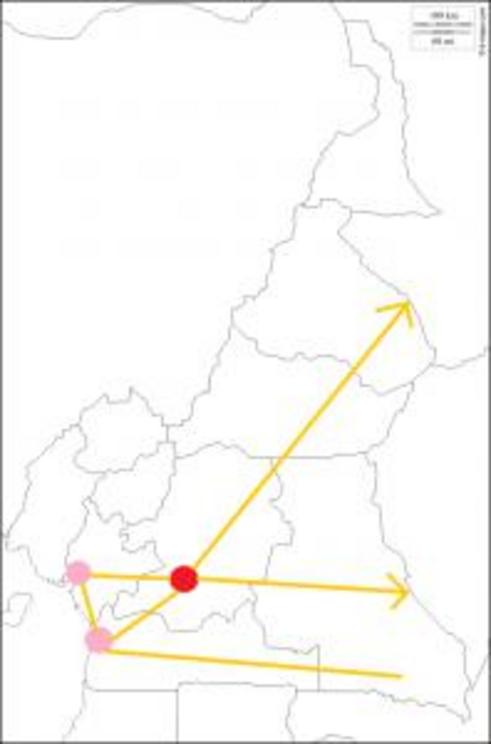

In connecting these two major port cities together, Cameroon is considering Chinese help in constructing a railroad between Edea, Kribi, and Lolabe, with the first city being located right near Douala and already linked to it by rail, while the last one is near Kribi and would link up with iron-rich southeastern Cameroon through the proposed Mbalam-Nabeda Rail Corridor. In aggregate, the connectivity vision that’s progressively taking shape in Cameroon is one in which its most important ports of Douala and Kribi are joined to one another by rail, and whereby these two maritime terminals are also in one way or another connected to the capital of Yaoundé. From there, goods could move to and from the Chadian capital of N’Djamena along the CCS Silk Road or to the Central African Republic capital of Bangui. To make this easier to visualize for the reader, the below custom map has been created to roughly document the approximate path of each respective corridor:

Red: Yaoundé

Pink: Douala and Kribi

Gold: Transport Corridors

The Threat To Cameroon’s “National Democracy”

Having laid out the geo-economic importance of Cameroon, both in terms of its domestic and international connectivity potentials, the research will now take a look at the internal problems that could arise to offset these interlinked visions. The summarized idea is that Cameroon is afflicted by the same types of structural destabilizations as Nigeria is, albeit on a smaller scale, though it might end up being Yaoundé’s collapse which catalyzes Abuja’s and not the other way around.

This is mostly due to the political-administrative nature of the Cameroonian state, which can be described as a centralized system in which an individual personality (President Biya) has an outsized strategic importance in decision making. The West usually refers to such models as “dictatorships”, but they could more objectively be described as “national democracies” that improvise for domestic conditions and don’t blindly follow the Western cookie-cutter template. In a country as diverse as Cameroon is, and with each particular group generally having defined geographies that could one day lay the basis for political-territorial claims (whether as independent or autonomous sultanates, regional groupings, city-states, tribal entities, etc.), it’s crucial for a centralized and unifying force to exist in holding everything together.

In terms of political administration and state symbolism, this is inarguably President Biya, though in practical on-the-ground terms, it’s the military and security services. Just like with the passing of Niyazov and Karimov in Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, respectively, the subsequent course of events will be dependent on the unity of the military and security services, and how quickly the elite can rally behind an agreed-upon replacement. If all goes according to plan and there are scant disruptions and a strong sense of “deep state” (permanent military, intelligence, and diplomatic bureaucracies) unity, then a smooth transition can be assured like in the aforementioned two cases, but if personal or identity-based ambitions get the best of the ruling and/or security classes, then the consequences could be disastrous.

In almost every example of a “national democracy”, the passing or resignation of the country’s leader serves as a potential Hybrid War trigger event in unleashing a series of preplanned destabilizations, with the variables surrounding this being both the previously discussed military-elite unity and the confidence that the anti-government organizers have in their plans. The best-case scenario is that the “deep state” remains unified and the provocateurs are caught off guard and unprepared by the structurally advantageous event, while the opposite one is that the “deep state” is fiercely divided amongst itself and the ‘revolutionaries’ are fully prepared for launching a Hybrid War. Sometimes, however, the reality is somewhere in the middle, with the “deep state” either being divided and the hostile organizers unprepared for exploiting this scenario, or the military and elite are unified in spite of the regime change proxies feeling confident enough to go forward with their initiatives anyhow.

It’s unclear at this moment how the course of events would progress in Cameroon’s case, since it’s challenging to find reliably objective information about either of these two determinants (military-elite unity and the confidence of anti-government organizers), so it’ll remain to be seen how Cameroon fits into this model. What is certain, however, is that the removal of President Biya from the political equation (whether by his eventual passing or resignation) would serve as a trigger event for exacerbating the already existing Hybrid War vulnerabilities present in the northern regions and the former territory of “British Cameroons”, both of which will now be discussed in depth. The reader should be reminded that these two levers of destabilization can be pulled to different degrees independently of the Biya trigger event, but that the chance of achieving their intended objectives vastly increases if timed to coincide with this scenario.

Geo-Demographic Determinants And Military Tactics

To refresh the reader’s memory about Cameroon’s ‘civilizational-religious’ internal divide, around a fifth of the country’s citizens are Muslim, with most of them residing in the densely populated northern reaches near the Nigerian and Chadian borders. Christians, on the other hand, comprise around 70% of the country and live mostly in the western and southern parts of Cameroon. It’s important to make note, just like in the case of Chad that was discussed in the prior chapter, that the physical geography of each community is inherently distinct and carries with it respective advantages and difficulties when it comes to Hybrid War. The Northern Muslims inhabit easily traversable desert and grassland terrain that could facilitate the rapid Daesh-like expansionism of Boko Haram if Cameroon ever experienced a large-scale state breakdown (such as in the midst of post-Biya successionist divisions), while the Southern Christians live in much more jungled areas that function quite differently under any Hybrid War scenario. Instead of the territorial conquest model of Daesh that Boko Haram would seek to emulate, the “Southern Cameroons National Council” (SCNC) separatists could wage debilitating guerrilla warfare in their thickly forested home regions, only selectively attacking certain cities and resorting to urban terrorism when they do.

From a tactical military perspective, these are two completely different types of wars that the Cameroonian Armed Forces need to prepare themselves for fighting, which requires highly professional training and a thorough understanding of the local terrain. Servicemen who are trained for operating in the desert Muslim North against Boko Haram might not be properly suited for combating the SCNC and its militant “Southern Cameroon People’s Organization” (SCAPO) in the jungled Christian South, and vice-versa. Moreover, Cameroon is susceptible to experiencing ‘traditional’ Color Revolution unrest in Yaoundé and Douala, whether linked to the Biya trigger event or not, which necessitates that the military also be prepared for urban warfare and crowd control contingencies as well. In sum, the Cameroonian military and security services must be prepared for waging desert, jungle, and urban warfare, further underscoring the necessity for this integral national institution to remain unified during any Hybrid War unrest and/or post-Biya successionist uncertainty, since any internal divisions among them during such a critical time would paralyze the state and prevent it from effectively fighting back against these existential threats.

Considering how irreplaceably crucial the military’s unity is in keeping highly diversified Cameroon together during any prolonged periods of uncertainty (e.g. post-Biya successionist rivalry), it might even turn out that a current or former representative of this institution takes the lead during this time in guiding the country out of or away from the abyss of Hybrid War and towards a stable and democratic transition. No other class of elites has the capacity to ensure all-around security and unity for the country than the military does, which explains why it’s most uniquely poised to play such a responsible role during the post-Biya transition, provided of course that it can remain unified during this time and becomes aware of its importance in determining the course of events. None of this can be assessed with any degree of confidence by the author given his lack of familiarity with such a specific institution, so further research into this vector should urgently be conducted by the appropriate experts in evaluating the likelihood of this scenario, since the alternative to military-elite unity (especially as regards the former) would likely be chaos and a structural replication of the Congo conflict in the West-Central Africa pivot (zipper) space.

Boko Knocking In The North

The two preceding sections were essential in establishing the proper context through which the reader can thenceforth analyze the most likely Hybrid War scenarios that could develop inside of Cameroon, so having explained the backdrop in detail, it’s appropriate to continue with an examination of the two most relevant possibilities that could happen. The first and most well-known is Boko Haram, which has proven itself to be a menace in Cameroon’s Far North and North regions, or in other words, the desert-grassland Muslim North that’s inherently threatened by non-state-actor expansionism. The Boko Haram problem and its prospective solutions can be divided into external and internal categories, both of which need to be elaborated on.

External Pressures:

From the international perspective, Northern Cameroon is in continual danger of being destabilized by any conflict overspill from the adjacent regions of its Nigerian and Chadian neighbors by virtue of its identical demographics and easily traversable geography. In the face of Nigerian capitulation and incompetency, Cameroon has had to rely on Chad for assisting it in driving out the terrorists and securing the western border, with its neighbor’s self-interest in this being to secure its nearby capital through the establishment of a stable buffer zone between itself and Boko Haram’s Nigerian-occupied homeland. Any prolonged state breakdown in Northern Cameroon would instantly endanger Chad by putting N’Djamena at risk, which is why the authorities there have proactively played the leading role in securing the entire Lake Chad basin, though to differing extents in Northeastern Nigeria due to the obvious sensitivities there.

Truth be told, it can be inferred that Cameroon also has some sensitivities as regards Chad’s emboldened military presence in the borderland area, since some Southern Christians might suspect that N’Djamena has future designs on the Northern Muslim regions such as carving out a sphere of influence for itself that’s stronger than the sovereignty that Yaoundé exercises within its own borders there. For now, at least ,this hasn’t resulted in any state-to-state problems, and Cameroon appears on the contrary to be quite satisfied with Chad’s military support and eager to rely on it in the future event that the situation once more veers on the edge of spiraling out of control. What can be learned from this is that there is a degree of Cameroonian-Chadian military interdependency in fighting against Boko Haram, with Yaoundé needing N’Djamena as necessary backup in case the situation suddenly goes awry while the latter needs its partner to be as stable and all-around effective as possible in functioning as a dependable buffer zone for protecting the capital.

Internal Pressures:

On the home front, Cameroon needs to carry out three main military goals and successfully enact a socio-economic policy for the Muslim North. Concerning the military objectives, the armed forces need to 1) prevent border infiltrations; 2) respond to successful infiltrators and sleeper cells; and 3) ensure urban security. It can fulfill these tasks by cooperating with its Nigerian and Chadian neighbors; preparing rapid response forces for targeted raids; and strengthening the capacities (and pay) of its local pro-government militias. Yaoundé absolutely needs to advance these three interlinked aims in order to make sure that the Muslim North remains as militarily secure from asymmetrical threats as possible, though that’s of course only half of what needs to be done in order to prevent an outbreak of regional destabilization in general. While Boko Haram is mostly an external threat of a physical nature, there’s also an internal and ideological one that must simultaneously be combatted as well.

The Cameroonian government must do everything in its power to rectify the feeling of differentness that the Northern Muslims feel towards the Southern Christians and the rest of the country. The social, economic, and political marginalization that some elements of this community experience could easily be taken advantage of by power-hungry demagogues and/or outside forces in generating simmering anti-government discontent that could one day blow over into its own Hybrid War scenario separate from Boko Haram. Even in an ideally secure environment, this still presents a troubling challenge that could burst to the regional forefront during the post-Biya transition and manifest itself in political ways through either Identity Federalism or outright separatism, which is why the government needs to craft and continuously reaffirm an inclusive patriotism that goes along with a comprehensive socio-economic plan for the region and this demographic. In order to fully achieve its internal ideological objectives for the Muslim North, Cameroon once more needs to turn to its Chadian neighbor, such as it had to do in regards to its external aims as described in the above section.

Regional Integration Solution:

The best way that Cameroon can safeguard its internal and external security is to integrate as much as possible with Chad, with the Northern Muslim area functioning as an experimental zone for constructing a shared Lake Chad core region between itself and western Chad (N’Djamena and its environs) that could then be expanded to the rest of their territories with time. The anti-Boko Haram coalition is a strong starting point for this in the military sense and it’s already provided many positive results for both sides, but the socio-economic component of this vision is sorely lacking in its effectiveness. For as positive of an idea as the Cameroon-Chad-Sudan (CCS) Silk Road is, barely any work has been done on the first two parts that would more tightly integrate these Lake Chad countries. A strong military partnership between two neighboring states without the compulsory socio-economic foundation is bound to become one-sided with time and run the risk of leading to a security dilemma after the shared motivation for their cooperation (in this case, Boko Haram) is no longer relevant, which is why it’s in the interests of long-term regional security (in its hard and soft forms) for the CCS Silk Road to be taken more seriously by both countries.

The grander vision that’s being expressed here is the construction of a strong integrated space east of Nigeria which could act as a military-economic bulwark against the overflow of Northern Nigeria’s numerous problems, with Cameroon and Chad implicitly agreeing on the urgency to do this out of their own mutually beneficial interests and the responsible need to proactively respond to the most likely forecasted threats emanating from this region. Moreover, even in the off-chance event that Northern Nigeria and the rest of the country could be sustainably stabilized, then it would be to Cameroon and Chad’s objective advantage to collectively deal with their (by then) much stronger neighbor than to do so individually, so it’s best to get started on the integration process as soon as possible than to be unprepared for this when/if the operative moment arrives. The first step in this process is to recognize that the geo-demographic continuity between Northern Cameroon and Western Chad and the two countries’ ongoing collective military efforts in the Lake Chad region afford a unique opportunity for both states’ leaderships to take their collaboration to the next level, which can most tangibly be attained by building off of their positive momentum in reprioritizing the CCS Silk Road between them.

Separatists Slithering In The South

Background:

The other substantial Hybrid War threat facing Cameroon are the “Southern Cameroons National Council” (SCNC) secessionists and their “Southern Cameroon People’s Organization” (SCAPO) militants that are battling to undo the 1961 reunification of Cameroon and the former British colony of “Southern Cameroons” and create their own ‘country’ called “Ambazonia”. As an historical backgrounder, the UK’s occupation of this part of the eventually united country occurred after World War I when the then-German colony of Kamerun was divided between the British and French. London also acquired another region called “Northern Cameroons”, but this Muslim-majority area chose to join Nigeria upon independence and was thus not unified with its namesake country like its southern counterpart was.

Nowadays the former territory of “Southern Cameroons” is divided into the Northwest and Southwest regions and is home to about 3 million people, or around 1/7 of the country’s total population. Although not incorporating the strategic port of Douala, “Ambazonia’s” claims run very close to the CCS Silk Road’s Atlantic terminus and it would obviously become a tempting target for future insurgents if they ever renew their campaign. Additionally, there are also a multitude of nearby soft targets in the adjacent West and Littoral regions that could be attacked by SCAPO in widening any forthcoming war and squeezing concessions from the government.

If the security situation deteriorated in these regions due to any number of high-profile attacks, then foreign investment and international trade could be expected to drop as a result, which could contribute to the compounding challenges that the Cameroonian government would experience during this time, to say nothing of the disastrous indirect affect it would have on the Chadian economy. It should be recalled at this moment that Cameroon’s northeastern neighbor depends on Douala for around 80% of its foreign trade, so it would be disproportionately more affected than perhaps even Cameroon itself if the SCNC/SCAPO militants launch a large-scale attack or intermittent campaign of terror against the port that results in a sharp decrease in its trading activity.

Federalist Fears:

Cameroon itself importantly underwent two political-administrative changes that directly relate to the “Southern Cameroons” issue. The country was first a federal republic from the time of the 1961 reunification until 1972, after which it evolved into a united republic until 1984, during which time it acquired its present state as simply being a republic.

The clear trend is that state centralization has strengthened throughout the decades and that the re-integrated area of “Southern Cameroons” began to be treated as a normal and equal part of the country on par with all the rest, as opposed to having any special federal status such as the one that it initially enjoyed. There’s nothing inherently wrong with this, though it is interesting that Cameroon moved in the opposite direction of most countries, which is to gradually devolve power to the provinces instead of centralize it.

The SCNC and SCAPO, while fighting for ‘independence’, might one day lessen their demands to federalization, which in that case would enable the scenario of Identity Federalism to spread throughout the entire country. In a sense, it might be worse for Cameroon to ‘federalize’ (internally partition) itself into a collection of ethno-regional-religious statelets, sultanates, and tribal entities than to simply ‘lose’ “Southern Cameroons”, but in any case, Yaoundé will do everything in its power to prevent either disaster from happening.

Regional Impact:

For the time being, the SCNC/SCAPO issue is under control and shows no signs of escalating, but the problem is that nobody really knows how much support this movement has among the locals in “Southern Cameroons” and whether ‘sleeper sympathizers’ might spring into action during a post-Biya trigger event. A more pressing threat, however, is that Southern Nigeria’s recent upsurge in neo-Biafra violence by the “Niger Delta Avengers” (NDA) might spill across the border and embolden the SCNC/SCAPO, with both militant separatist groups dangerously having the opportunity to link up and join forces in maximizing their power and provoking an international conflict.

The NDA is a rag-tag collection of bandits that follow in the footsteps of their Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) predecessors which in turn grew out of the forces previously responsible for launching the Nigerian Civil War, otherwise known as the Biafra War, of 1967-70. Their main complaint was that the people of oil-rich Southeastern Nigeria weren’t receiving their fair share of financial reimbursement from the energy resources under their soil and off their coasts, which is one of the main reasons why they first began agitating for the Eastern Region to become independent as the state of “Biafra”. Across the border nowadays, their SCNC/SCAPO counterparts don’t have any such wealthy energy resources to claim as their own in their prospectively independent “Ambazonia”, but they do have an historical and linguistic legacy of separateness as the Anglophone UK-administered colony of “Southern Cameroons” which could be manipulated to further divide the population from the rest of their French-speaking Cameroonian peers and incite more support for secessionism.

Neither the NDA nor SCAPO are powerful enough to succeed on their own, which is why both of them must tactically ally with other non-state actors in order to achieve their separatist objectives. If either of these allied or informally coordinated their anti-government activities with Boko Haram, then it would seriously complicate their respective governments’ efforts in dealing with both insurgencies by dividing their attention along two separate directions and battlefield geographies. There’s no convincing proof that this has happened, at least not yet, but it’s a disturbing possibility that must be responsibly countenanced by decision makers in both states. Equally as discomfiting is the International Business Times’ February 2016 report about how the “Biafrans” and “Ambazonians” could team up in turning their individual insurgencies into a unified campaign, which in that case would immediately produce an international crisis in the Gulf of Guinea that neither Nigeria nor Cameroon might be properly suited to handle, let alone in the coordinated manner that this would necessitate.

The internationalization of the “Biafra” and “Ambazonia” insurgencies and their amalgamation into a single crisis could end up being the catalyst for further state failure in both Nigeria and Cameroon, and the urgent attention that Abuja and Yaoundé would have to pay to this problem might create opportunistic space for a Boko Haram comeback campaign. Additionally, the sensitivity of cross-border operations in one another’s territories might lead to disagreements and tension between the two neighbors, no matter their shared goal in pacifying the transnational space, thereby hampering the effectiveness of any supposedly coordinated actions and working out to the ultimate benefit of the insurgents.

Solution:

The “Southern Cameroons” movement has been militantly dormant for quite a while, but that in and of itself can’t be taken as a surefire sign that it’s politically inactive. The lack of visible on-the-street support for the SCNC/SCAPO might be simply because of the groups’ illegality and Yaoundé’s tireless efforts to root it out of society, but the separatists might suddenly emerge as a force to be reckoned with during any period of nationwide political uncertainty and destabilization (e.g. the post-Biya transition). Because of this, Cameroonian officials must not only be alert for any signs of the group’s physical resurfacing, but should also be proactive in snuffing out its appeal once and for all, which calls for bridging together military and ideological objectives into a comprehensive anti-insurgency package.

In principle, the most obvious solution is to deepen Cameroon’s full-spectrum integration with Nigeria and use “Ambazonia” and “Biafra” as springboards for bringing this about, but right now it’s unsafe to do to this in as fast and open of a manner as may be needed because of the NDA’s renewed militancy and the risk that it has for spilling across the border and emboldening the SCAPO. It’s unavoidable that these two countries will sooner or later move closer out of natural economic logic and the impetus that the Chinese-financed CCS Silk Road will provide, but it’s crucial at this moment that any progressive movement in this direction is balanced and cautious in order to avoid the foreseeable pitfalls that were earlier described above.

Therefore, it’s advised that Cameroon begin by building off of the working contacts and operational coordination that it has with the Nigerian military through their joint participation in the anti-Boko Haram Coalition and initiate something similar, lesser-scaled, and more proportionate along their southern “Ambazonia”-“Biafra” borderland. There obviously wouldn’t be any cross-border strikes at this point because the situation has yet to deteriorate to that level and become interlinked enough to justify it, but this would be a responsibly proactive first step in case that ever eventuates. After having secured the border between them, Cameroon and Nigeria could then move towards enhancing their economic and socio-cultural linkages in order to prepare themselves for the surge in connectivity that will occur once the CCS Silk Road is finally completed.

Cameroon As The Transregional Zipper

One of the main arguments made in this research is that Cameroon has the potential to zip and unzip the transregional West-Central African space, with the outcome ultimately depending on how well it can manage the Hybrid War threats of Boko Haram and the SCNC/SCAPO. If Yaoundé is unsuccessful in handling these problems, then Cameroon might implode and its subsequent destabilization could send immediate aftershocks throughout the transregional space, thereby setting off a possible chain reaction in Nigeria and Chad. On the other hand, Cameroon could bring these two countries closer and connect the space between them and beyond due to its unique geography and the enormous potential that the CCS Silk Road has in fundamentally transforming West-Central African geopolitics, provided of course that it’s eventually completed.

The reader may have picked up on the fact that the author’s suggested solutions for dealing with Boko Haram and SCNC/SCAPO are structurally identical and differ only in the local-regional specifics of their application. The primary point being proposed in both instances is that the transnationalization of either space – be it the Muslim North or the Anglophone West – doesn’t necessarily have to be a bad thing if it’s handed the right way, which in this case is with the intention of fostering robust multidimensional integration between Cameroon and its Chadian and Nigerian neighbors. Building off of the security impetus that most urgently unites the country with each of counterparts, it’s possible to broaden the established sphere of military cooperation into economic and socio-cultural directions, with the CCS Silk Road functioning as the backbone for this transregional endeavor.

The conceptual vision is for Cameroon to leverage its civilizational diversity as an instrument in getting closer to each of its two main neighbors, with the eventual goal of becoming the geo-identity ‘zipper’ that holds them together and functions as the core transregional entity connecting West and Central Africa. Cameroon’s geographically central position in this construction, compounded with the connectivity potential that its Northern Muslim and Western Anglophone regions have in integrating with their cross-border counterparts, provides Yaoundé with a strategic opportunity to turn what might otherwise be a Hybrid War disadvantage into a New Silk Road advantage. If the competent authorities become aware of their country’s strategic attributes, and take actionable steps to mitigate the obvious dangers while embracing the integrational potentials, then Cameroon could flourish into one of the most prosperous countries in Africa and become the envy of the world’s Great Powers.

The “Weapons Of Mass Migration” Wildcard

The last thing to discuss when detailing Cameroon’s Hybrid War vulnerabilities is the wildcard that is “Weapons of Mass Migration” (WMM), the (inadvertent or deliberate) asymmetrical warfare weapon first described by Harvard researcher Kelly M. Greenhill in 2010. Cameroon is incapable of directly influencing its neighbors’ affairs aside from the unintentional overspill of its own domestic problems, so it’s powerless to determine whether or not a WMM-producing conflict occurs in its transregional neighborhood. This is why the instance of WMM are such a wildcard, because they’ simply outside the control of the Cameroonian authorities, yet the government is still forced to immediately respond to its occurrence if it arises. The uncontrollable influx of refugees or refugee-disguised insurgents into Cameroon’s border regions could contribute to more domestic destabilization and might push one or both of the country’s main Hybrid War scenarios past the tipping point and into a full-fledged problem.

All-Compass Threat:

WMM could swarm Cameroon from any direction, with the following being the most likely causes for each compass point’s destabilization:

* North – Boko Haram

* East – Central African Republic (CAR) Civil War

* South – Equatorial Guinean state failure during a tumultuous post-Mbasogo transition

* West – “Biafra” violence

The northern and western vectors have already been described above when analyzing the consequences of Boko Haram and a transnational “Biafra”-“Ambazonia” insurgency, so the research will thus address the eastern and southern threats in the final two subsections.

The Central African Republic’s Civil War:

The civil war that made the Central African Republic (CAR) ungovernable and devolve into a failed (or some would even say, non-existent) state is a pressing problem for Cameroon’s stability owing to the very real threat that it has for producing wave after wave of WMM. Cameroon already hosts 300,000 refugees from the country, most of whom it could logically be inferred are based in the Eastern border region. Although Cameroon boasts a population in excess of 22 million people and less than a third of a million refugees might seem like an insubstantial and easily manageable sum in aggregate, the reality is that the Eastern region where most of them likely reside only has a population of 800,000 or so.

This means that a significantly proportional number of the people in this part of the country aren’t citizens, but refugees, which could obviously lead to problems between the newcomers and the indigenous inhabitants if their interactions aren’t closely controlled. For example, if the CAR refugees live in camps outside of the main cities and villages, then it’s less likely that any local Cameroonian will even be aware of their presence or be impacted by it in any tangible way, but if these newcomers live in the same cities and villages as the locals and visibly compete with them for jobs and resources, then it could predictably lead to a flare-up of violence one of these days, one which the government would understandably like to avoid.

The most sustainable solution that Cameroon could work towards in preventing a surge of WMM from the CAR is to take the lead in helping to resolve the country’s civil war. To remind the reader, the CAR is torn apart by engineered ‘civilizational’ violence between its Christian and Muslim geographic (but not demographically equal) halves, and it’s here where majority-Christian Cameroon could step in alongside its majority-Muslim Chadian strategic ally to mediate in the country’s conflict. The details are unclear at this stage for how this would work in practice, but the strategy is that Cameroon and Chad could work in partnership with one another in leveraging their ‘civilizational credentials’ as a way to gain the trust of each respective confessional community, after which Yaoundé and N’Djamena would then apply their newfound influence in encouraging their local allies to enter into a long-lasting compromise that would work out to all sides’ multilateral benefit.

From Cameroon’s perspective, the quicker that peace returns to the CAR, the sooner that the Douala-Bangui Corridor could be built, while Chad’s interest is in maintaining stability along its southern, porous, and highly demographically sensitive border for the reasons explained in the previous chapter. Both sides would obviously benefit from the reduced potential for WMM as well, but it might be the immediate economic-security incentives that serve to motivate decision makers in Yaoundé and N’Djamena to finally take the bold and coordinated steps necessary in resolving their shared neighbor’s ‘civilizational’ conflict.

Equatorial Guinea Erupts In Violence:

The second wildcard event that could happen in producing swarms of WMM against Cameroon would be if neighboring Equatorial Guinea erupts into violence during a tumultuous post-Mbasogo transition. President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo has been ruling his tiny and oil- and gas-rich country since 1979, during which time he’s cultivated very close relations with the US. Although Equatorial Guinea is very geographically small, it therefore has an outsized geostrategic importance in regional affairs. What’s most peculiar about it, aside from the fact that the same leader has been in power for nearly four decades (and his uncle ruled for ten years before that prior to his overthrow), is that the country is geographically discontiguous and is divided between insular and littoral halves.

Whenever the elderly leader inevitably passes or resigns, the exact same ‘national democracy’ scenario that was described above for Cameroon will enter into effect, whereby the stability of the country will be largely determined by the military and elite’s unity during the subsequent transitional period. If a Hybrid War is launched against the authorities and/or divisive infighting leads to an outbreak of conflict and nationwide unrest, then it’s foreseeable that many of the locals might try and flee their country for abroad, with the lion’s share of them predictably arriving in Cameroon due to the country’s convenient proximity. Even the main island of Bioko is just 32 kilometers away from the continental coast and very close to the major Atlantic port of Douala, thus underlining how easy it would be for WMM to escape their country and come to Cameroon.

What might be more important than preparing for any potential WMM from Equatorial Guinea is deciding what role Cameroon could play in deciding the post-Mbasogo future of the country. In and of itself, Cameroon doesn’t have any sway over what happens in its neighbor’s affairs, but its geography critically affords it with an easy chance to do so during any potential humanitarian crisis, whether it directly intervenes or indirectly allows its territory to be used by others who do so instead. It’s not known what the Cameroonian Armed Forces’ contingency measures are in the event of such a scenario, but given the active role that France plays in the region, it’s foreseeable that it might order its Libreville-based troops in the Gabonese capital to involve themselves in the Equatorial Guinean mainland while requesting basing rights from Cameroon in facilitating this for Bioko.

If prompted to respond to these rapidly changing circumstances, Cameroon will have to calculate its expected benefits from each course of action, which could be simplified as either doing nothing at all and only reacting to events within its own borders, or taking the lead in carrying out or facilitating an intervention in the neighboring country. More than likely, Yaoundé won’t behave unilaterally as regards the second scenario branch, and would likely only make a move in this direction if it had Paris’ support and/or did so as part of a joint operation with France. In that case, Cameroon must think about what it would stand to gain by doing so and how it could bargain its future position in order to receive the most benefit from its former colonial master. After careful consideration, though, it might even be decided that it’s to Cameroon’s ultimate benefit to stay out of this possible conflict and retain its foreign policy neutrality.

To be continued…