EU poised to create massive transatlantic facial-recognition database

... link with US

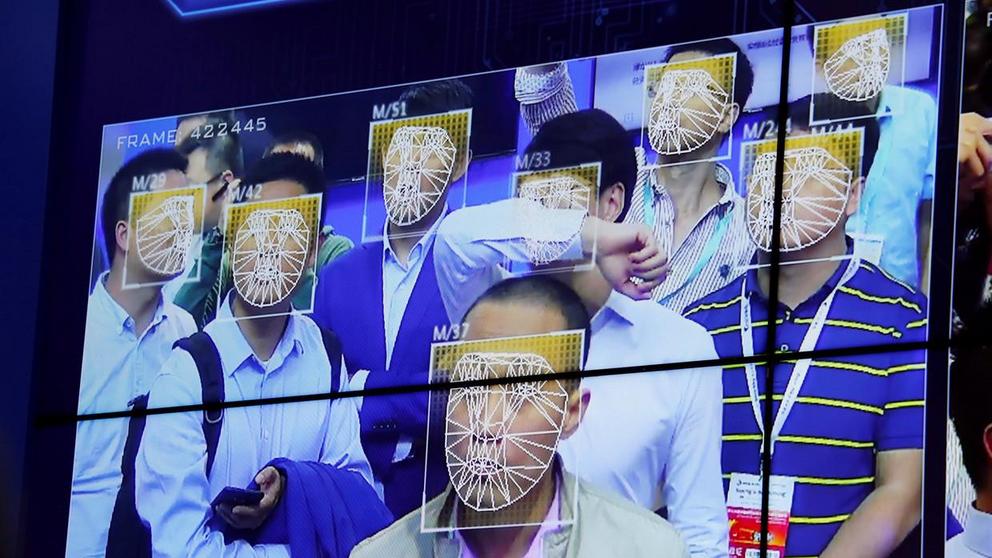

The EU is laying the groundwork for a massive international facial recognition database that may someday hook into the one maintained by the US, according to leaked internal documents.

National police forces of 10 EU member states are calling for a legal framework to create a massive system of interlinked facial recognition databases “as quickly as possible,” a report leaked to the Intercept on Friday reveals. Austria is leading the way on the project, which was still in its early phases as of November, when the report initially circulated among EU officials.

Produced as part of a project to expand Prüm, the EU-wide database-cross-referencing system that already allows for all-at-once scanning of individual DNA, fingerprint, and vehicle registration databases, the report calls for EU legislation that would create and connect country-level facial recognition databases, potentially all the way to the US. Because the US already has a Prüm-like exchange in place with countries that are part of the Visa Waiver Program, including most EU member states, some – including the alarmed EU official who allegedly leaked the report to the Intercept – believe any future facial recognition database network would include the US by default.

Brussels is pouring significant resources into plotting out this layer of the surveillance state, involving both private and public sector. Consulting firm Deloitte was paid €700,000 last year to deliver a report on upgrades to Prüm, focusing in part on facial recognition, while a €500,000 initiative bankrolled by the European Commission engaged a group of public agencies to “map the current situation of facial recognition in criminal investigations in all EU member states” with the goal of moving “towards the possible exchange of facial data.”

In April 2019, legislation merged five EU databases holding fingerprints, facial scans, and other biometric data to create a single repository of information on 300 million non-EU citizens. While Deloitte recommended the EU do the same with police facial recognition databases in its November report, law enforcement officials apparently balked. However, linking the various countries’ facial scan databases with a Prüm-like cross-check system would ultimately have the same privacy repercussions as merging them.

Because the US Department of Homeland Security has required participants in the Visa Waiver Program to adopt data-sharing agreements ever since 2015, any facial recognition databases constructed going forward would presumably have their contents shareable with the US. This has been something the US has pursued in Brussels since at least 2001, when Washington negotiated a pair of agreements to share both analytical and personal data between Europol and US law enforcement agencies; however, Europol's inability to collect the data itself meant it was dependent on what was supplied by member states. A facial recognition database in every nation, hooked into a central data-sharing network, creates an enviable transatlantic trough at which everyone's law enforcement can feed.

The rollout of facial recognition in Europe hasn’t been smooth, however. Efforts to deploy it as a policing tool in Scotland were placed on hold earlier this month, after a parliamentary committee concluded human rights concerns made it unfeasible. A pilot program in London is expected to begin this month, despite harsh criticism from civil liberties groups, after an earlier program was declared a failure last January.

The US has also hit a few bumps in the road in its march toward a facial-recognition-enabled surveillance state. In December, the Department of Homeland Security canceled a program that would have required all Americans to submit to compulsory facial scans at airports after concerns about both privacy and whether the technology was able to perform.

Meanwhile, the US is expanding and consolidating its own biometric databases, paralleling the EU’s streamlining of Prüm. Last June, DHS added DNA profiles and “relationship patterns” gleaned from social media to its upgraded Homeland Advanced Recognition Technology (HART) System, bringing the existing database – which already includes fingerprints, iris scans, and facial recognition – onto the Amazon cloud, where most other US government agencies already store their data.