Troubled firm aims to mine Madagascar forest for rare earth elements

Singapore-based ISR Capital is under investigation for financial misconduct related to its acquisition of a rare earth mining project in northwestern Madagascar. The project faces stiff local opposition due to its potential impact on the area’s people and wildlife. by Edward Carver on 8 August 2017

- A Singaporean company called ISR Capital is working to develop a rare earth mine on Madagascar’s highly biodiverse Ampasindava peninsula. The company faces an investigation by financial regulators and turnover among its top executives.

- The mining of rare earth elements needed for cell phones and many other modern devices can have severe environmental and health impacts. This would be the first such mine in Madagascar.

- The Ampasindava peninsula is home to a number of threatened lemur species that could be further imperiled if the mining project goes forward, scientists warn. Local farmers and tourism operators oppose the project, fearing it could contaminate land and water.

AMPASINDAVA PENINSULA, Madagascar — Solondraza, a 63-year-old farmer in northwestern Madagascar, has led a mostly conflict-free life. He and his wife live in a small house made of ravinala, a type of palm tree that fans out across the hilly landscape. They earn a living on cash crops like vanilla and cacao that grow well in the tropical environs, and this has allowed them to support their 18 children and 54 grandchildren, most of whom still live in and around their village of Befitina.

But in recent years Solondraza has become something of an activist, organizing meetings and rallying neighbors. He wants to stop a foreign-owned company, Tantalum Rare Earth Malagasy (TREM), from mining his land for rare earth elements.

“Our ancestors survived here by living off of the land,” Solondraza said. “If TREM comes here to destroy that harmony, I fear for my children’s future. We do not want TREM and we do not need them.”

Solondraza inspects vanilla plants near his home. Coffee beans are on the trees just behind the vanilla. Cash crops such as these are the main livelihood for Ampasindava families. Photo by Edward Carver for Mongabay.

Befitina is part of TREM’s 115-square mile (300-square kilometer) concession on the Ampasindava peninsula, a highly biodiverse area jutting out into the Mozambique Channel, several hundred miles east of the coast of mainland Africa. Ampasindava is home to a number of threatened lemur species that could be further imperiled if the mining project goes forward, scientists warn. The peninsula is also just across the water from the island of Nosy Be, Madagascar’s main tourist destination, where business owners worry that mining pollution could turn visitors away. Rare earth mining can have severe environmental and health impacts, research from China shows.

TREM’s explorations show Ampasindava to be rich in the valuable rare earth elements needed in electric motors, computer parts, cell phones, and many other modern devices. The company managing the project has touted the “exceptionally promising” findings in Ampasindava, and the concession has twice been appraised at over $1 billion. (However, financial regulators rejected the appraisal methods and a third appraisal is now underway. This week, ISR Capital indicated that the upcoming appraisal would be much lower.) It is an ionic clay deposit, which are valuable for having rare earth elements that are relatively easy to mine and process. Only a few such deposits have been discovered outside of China, and the one in Ampasindava is considered especially large.

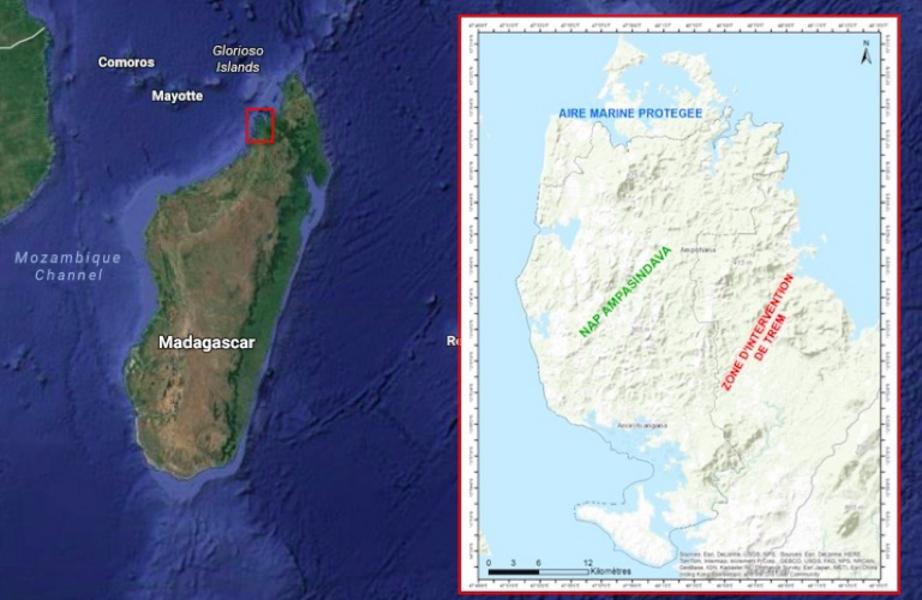

Maps show Madagascar’s Ampasindava peninsula, with its marine protected area (blue writing), terrestrial protected area (green writing), and TREM rare earth mining concession (red writing). Background map courtesy of Google Maps; Ampasindava peninsula map by Association Famelona.

Directly beside TREM’s concession is a protected area that covers the rest of the Ampasindava peninsula. The area was granted protected status in 2015, but only after TREM successfully lobbied to reduce its size, in order to safeguard the boundaries of the concession.

In early 2015, two high-level government officials were flown into Ampasindava on a TREM-chartered helicopter, according to several people affiliated with Missouri Botanical Garden in Madagascar, which manages the protected area. A few months later, in July 2015, Madagascar’s government decided that the Ambongomirahavavy mountain area, which is the source of 80 percent of the peninsula’s water and had been slated for inclusion in the protected area, would remain part of TREM’s concession.

“The government’s position was clear — they were pro-mining,” a Malagasy botanist involved with the negotiations told Mongabay. “Their interest in the environment was zero.”

TREM viewed the negotiations differently. “I do not have precise information on how the negotiations went but TREM obviously was interested in the end results and it would be logical that TREM lobbied for a limited area to be protected in its concession,” Markus Kivimäki, the CEO of Tantalus Rare Earths AG (TRE AG), TREM’s longtime parent company in Germany, wrote in an email to Mongabay.

A view of the Ampasindava protected area, taken from Andranomatavy Mountain. Photo by Rêve d'Ailes photographie.

“Certain challenges at the buyer”

Last year, TREM was sold and resold in deals that have since been scrutinized by regulators. A private Singapore-registered company called REO Magnetic bought TREM from TRE AG, and then sold a major stake to another Singapore-based firm called ISR Capital.

As it moved to acquire TREM, ISR’s stock price skyrocketed, only to crash several months later. ISR is under investigation for a violation of Singapore’s Securities and Futures Act, which covers crimes such as market rigging and stock manipulation. Prosecutors have linked ISR to the mastermind of a 2013 “penny stock scandal” that is considered one of the largest financial crimes in Singapore’s history; in a court document, they claimed that the so-called mastermind “was intimately involved in, and exercised influence over, the management and corporate affairs of ISR.” At least four ISR executives have resigned since November.

TRE AG still manages TREM, for now, as neither the sale to REO nor the resale to ISR has been finalized. TRE AG handed over management to REO last September, but had to retake control in March due to what Kivimäki called “certain challenges at the buyer.”

To read a detailed timeline of the TREM deals and the Singaporean authorities’ investigation of ISR Capital, click here.

Nonetheless, to investors and regulators, ISR Capital has expressed confidence in its ability to “accelerate” the project. ISR has not advertised the fact that TREM now has no active permits of any kind. TREM’s exploration permit ran out in January of this year and the company has not taken samples since that time. Yet TREM still has two guarded compounds and at least one other fenced-off area in Ampasindava. In an email correspondence, Kivimäki, TRE AG’s CEO, did not directly respond to questions about why TREM still has a presence there. He said that TREM has applied for another exploration permit.

In 2016, the government’s National Environment Office authorized TREM to commission an environmental impact assessment of its plans for pilot production in Ampasindava. However, over a year later, no assessment has been turned in to the office for approval. Pilot production cannot begin until the NEO has approved the assessment.

The opaque nature of the deals and the possible misconduct could raise concerns about who exactly is managing a large and potentially dangerous project in Madagascar, a country where corruption often undermines conservation efforts. But it appears that no one in Madagascar who is involved with the project, aside from possibly TREM’s employees, is aware of the parent companies’ troubles. None of the dozen-plus NGO workers and scientists involved with Ampasindava whom Mongabay interviewed for this story mentioned them. And in interviews with Mongabay, employees at two government ministries indicated that they were unaware of them.

“In general, this ministry is interested in the impact of the activities,” Jean Romain Randrianarisoa, director of environmental evaluations at the Ministry of the Environment, Ecology, and Forests, told Mongabay. “If the work is being done legally and orderly, we aren’t following who’s on the other side of the business.”

A scientific field camp visible above the foliage on Andranomatavy Mountain, a part of the Ampasindava peninsula that the locals consider sacred. Photo by Leslie Wilmet.

Local frustration

TREM’s presence in Ampasindava has not been entirely unwelcome. The company has helped to build three schools, five bridges, and a brick church for local communities. It has also employed local men as day laborers for months at a time, usually to dig exploration pits. The pay is just over $2 per day. A few men also have full-time jobs as guards.

People in Ampasindava need the work, as they have few other sources of income. “The only reason we like the company at all is because it is hard to find money, so we always tend to be happy when there is work,” a resident of the village of Betaimboay, near one of TREM’s two local compounds, told Mongabay. “The salary is low, but if you don’t have any money, you have to work. It is not because you like working with them.”

After several years of exploration, people in Ampasindava have grown weary of TREM. Women say that TREM discriminates against them and has never hired a woman as a manual laborer or guard. “They say that women can’t do the work like digging the holes, so they only take men,” said Catherine Soamalaza, the president of a women’s group in Befitina.

Theogene, a local farmer, looks down at a TREM exploratory pit just behind his house. There are several thousand such pits in the concession area. Photo by Edward Carver for Mongabay.

People are also frustrated by the number of exploratory pits TREM has dug: several thousand, most of them ten meters deep. Worse, they say the company has failed to refill the holes properly, and the uncovered wells trip up zebu cattle. Once injured, the highly prized zebu, a major source of local wealth, have to be killed. Mongabay saw dozens of uncovered pits in the area.

“They just cover the pits beside the street so that when there is a supervisor passing by the pits look covered,” Theogene, a young farmer in Ankintsopo, a village in the center of the concession, told Mongabay. “The pits further away are not covered. That’s the truth here.”

In response to Mongabay’s questions, Kivimäki wrote, “The process for these pits is such that they are opened, samples are taken, they are filled and the area rehabilitated. This means that, contrary to certain allegations, TREM has not left any open pits from the earlier campaigns (2009 to 2015). The process to close the pits from Autumn of 2016 has been ongoing since June and should be finalized relatively soon.”

A green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) digs a nest on a beach on the Ampasindava peninsula. Photo by Leslie Wilmet.

Impact unknown

But the pits are minor inconveniences compared to what may come. The negative environmental and health impacts of rare earth mining can be serious. “There is little understanding internationally of the true human costs of rare earth mining,” wrote Julie Klinger, an international relations professor at Boston University and author of a forthcoming book on rare earths, in a 2013 essay.

Deposits in southern China, to which ISR Capital has compared the Ampasindava deposit, have badly contaminated the soil of nearby farmland. Locals there have high levels of rare earth elements in their blood and hair, according to a 2013 study. Rare earth deposits are known to contain radioactive materials that can contaminate land and water, although clay deposits like the one in Ampasindava usually have low levels of radioactivity. A BBC correspondent traveling to Baotou, a center of rare earth mining in China, described it as “hell on Earth” and members of the Chinese Academy of Sciences assert that “irrational exploitation of rare earth resources has caused severe damage to local ecologies” in a new paper.

Yet so far, there has not been an environmental impact study of the exploitation phase of TREM’s project.

The extent of the environmental damage in Ampasindava will depend in part on what extraction method is used and whether separation and refinement are done on site. Neither decision has been made by TREM, according to Kivimäki. TREM has no plans to separate, purify, or refine rare earth elements in Ampasindava. Kivimäki said that plenty of refining facilities already exist in China, and TRE AG perceives no need to do such work in Madagascar.

Yet it is not clear how high volumes of raw materials would be exported from Ampasindava, a rural area with poor infrastructure and no major port. And TREM is scheduled to be under new management within the next six to nine months — that of REO Magnetic or ISR Capital — so even the rough scenario Kivimäki outlined could change. Neither ISR Capital nor REO Magnetic’s lawyer responded to requests for comment for this story.

The lack of clarity with regard to TREM’s plans makes it hard to predict the project’s environmental impact. “Without disclosing what sort of chemicals they will use to separate the rare earth elements, and in what manner they will be used, the company cannot credibly state that they will extract these elements in an environmentally friendly manner,” Klinger wrote in an email to Mongabay after reading an ISR Capital filing that asserts that the Ampasindava deposit could be mined in a relatively easy, environmentally friendly way.

China has provided 85 percent or more of the world’s rare earths for the last few decades, but authorities there have been reluctant to disclose the environmental impacts, according to Klinger, who speaks Mandarin Chinese and did research in Bayan Obo, the self-proclaimed Hometown of Rare Earths. “Some true locals are tragically recognizable by their blistered skin and discolored teeth, indicating severe chronic exposure to arsenic leaching out of the mine,” Klinger wrote in her 2013 essay.

Demand for rare earths is rising, especially for neodymium, a light rare earth used in high-tech magnets, and terbium and dysprosium, heavy rare earths used in screens and nuclear reactors. But in the last eight years, China has tried to control its output of rare earths and improve its environmental record. In 2012, as China closed dozens of rare earth facilities, a government minister said that the country was “absolutely not willing to sacrifice the environment in order to develop the RE industry.” Investors have thus increasingly focused on places like Ampasindava, where ISR Capital’s executive chairman Chen Tong has asserted that elements such as neodymium, terbium, and dysprosium are abundant.

The 30,000 or so people on the Ampasindava peninsula have begun to learn about these economic forces from civil society groups in the nearby towns of Nosy Be and Ambanja. Some villagers have seen a video produced by the Research and Support Center for Development Alternatives, an environmental advocacy group in Antananarivo, Madagascar’s capital. Raymond Mandiny, an Ambanja resident who has relatives in Ampasindava, has spent time in the villages teaching people about the potential consequences of rare earth mining. He traveled to Antananarivo in June to ask government ministries to deny TREM any further permits. Joel Soatra came along to represent the tourism industry in Nosy Be. At a press conference, they called for an immediate end to the project.

A Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) on the Ampasindava peninsula. Photo by Leslie Wilmet.

An unknown species of lizard on the Ampasindava peninsula. Photo by Leslie Wilmet.

“The impacts could be irreversible,” Soatra told Mongabay just afterwards. “If radioactivity touches our biodiversity, we cannot step back and heal it in a hospital. So it’s better for us to be careful. If we feel that it won’t go well, it’s better to stop here.” He said he worries that TREM could ruin the beauty and biodiversity that draws tourists to the area, and that the Lokobe Reserve on Nosy Be and the surrounding Bay of Ampasindava could be polluted.

Jean Romain Randrianarisoa, the environment ministry’s director of environmental evaluations, acknowledged that rare earth mining is new to Madagascar. But he said he hoped that government officials could be trained to regulate it properly.

In 2015, the Ampasindava peninsula — except for the TREM concession — was formally designated as a protected area, after being a temporary reserve for many years. An area of over 350 square miles (900 square kilometers) is now protected. Eighty percent of the plants are endemic to Madagascar, and 8 percent exist only on the peninsula. At least eight species of lemurs live on the peninsula, and six of them are endemic to northwestern Madagascar. Six are listed as Endangered by the IUCN; the two others are Vulnerable.

One of those listed as Endangered is the Mittermeier sportive lemur (Lepilemur mittermeieri), a mostly nocturnal primate that is found only on the peninsula. Research by Leslie Wilmet, a doctoral student in conservation biology at the University of Liège and Gembloux Agro-Bio Tech in Belgium, indicates that only about 10,000 of these lemurs remain. She has spent much of the past four years in Ampasindava studying this species, and she is concerned about the potential impact TREM could have on it.

“The problem with the TREM project will be that lots of forests will disappear,” she told Mongabay. “The territory will be considerably reduced for this species. We don’t know if the species will survive or not if the project goes on.”

Other scientists agreed that TREM’s work could damage the protected area. Jeannie Raharimampionona, head of conservation at the Missouri Botanical Garden’s Madagascar program, said the buildup to exploitation would bring lots of new people to Ampasindava, putting a strain on water and forest resources. “The change in lifestyle will happen quickly,” she predicted. “We won’t be able to manage the massive changes.”

A female (left) and male (right) black lemur (Eulemur macaco). The species lives only in northwestern Madagascar. (Photos are not to scale.) Photos by Leslie Wilmet.

The land of the ancestors

Likewise, many local people worry that their future crops are at risk. In 2014, a group of concerned locals, including Solondraza, formed a farmers’ group that seeks to protect the land from TREM. Delphin Malazamanana, the group’s president, says he felt called to organize the opposition.

“We felt in danger because of the big company that bothered us and underestimated us,” Malazamanana told Mongabay. “So we had the idea to protect ourselves by creating this group.”

The group meets in an open-air hut in Befitina, a village on the western edge of the concession, near the protected area. At a recent meeting, Rosé Mamory, the village president, explained that his office had never been shown TREM’s permits. “It is our land,” he said, waving at the verdant bamboo and ravinala forests around him. “No one here gave the land to them. It was the national government that did that.”

Sitting on a dirt floor beneath a thatch roof, men stood up one at a time to speak about corruption at the national and local level. They believe that TREM wins support from government ministers and local mayors by bribing them. (When Mongabay arrived in Antsirabe, one of six counties in the concession area, the mayor was visibly displeased and asked repeatedly if something negative would be written about TREM. However, this investigation turned up no direct evidence of corruption.)

In Madagascar, respecting the ancestors means respecting the land. One’s home village is the tanindrazana, “the land of the ancestors,” — where they lived, worked, and were buried. Solondraza wonders what will become of the buried ancestors. “Even our ancestral tombs will be destroyed,” he said. “That’s not our culture.”

Solondraza’s very name means “replacement for the ancestors,” and the biggest question now, with a mining company bearing down on his land, is whether Solondraza’s own replacements will have a decent place to live.

An unknown species of chameleon that resides on the Ampasindava peninsula. Photo by Leslie Wilmet.

For the rest of this article please go to source link below.

For full references please use source link below.