Unexplored African lakes reveal hidden world

Even for the team of seasoned adventurers, exploring each new river section that feeds southern Africa's Okavango Delta presents unique challenges—but no matter what, there are always hippos.

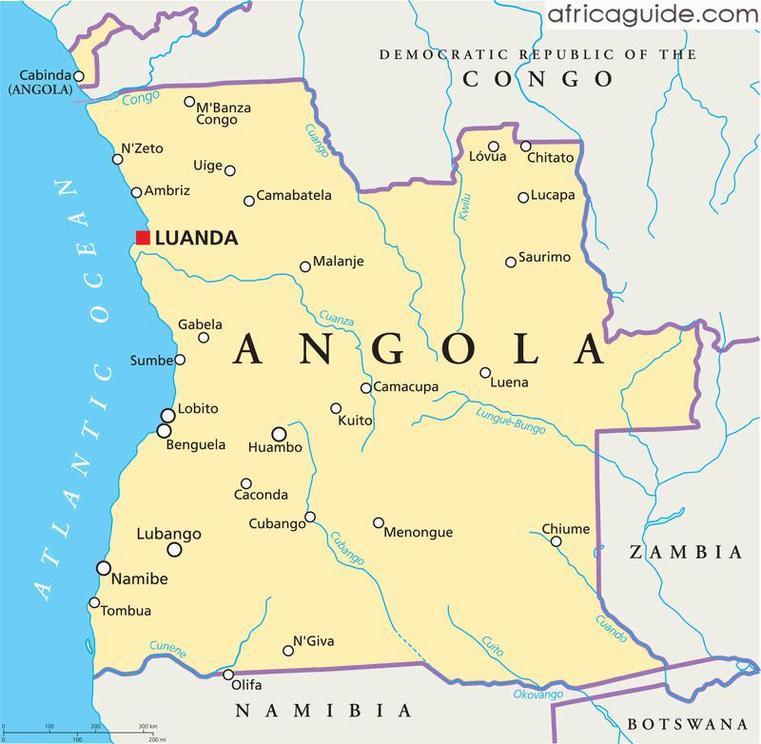

From April to July of 2017, the explorers, part of National Geographic’s Okavango Wilderness Project, continued pushing their way into uncharted territory in the Angolan highlands, seeking to understand and define the mysterious region that feeds the Okavango River Basin. A UNESCO World Heritage site, the Okavango Delta is known best from its terminus in Botswana, but the goal of the Okavango Wilderness Project is to explore the rivers and lakes that feed the delta, which run throughout Angola, Namibia, and Botswana.

Steve Boyes, a conservation biologist and National Geographic explorer, has been a project leader since the beginning in 2015, when the team began formally describing the biodiversity and characteristics of the Angolan highlands’ rivers for the first time (at least in terms of Western scientific knowledge, as the region has been inhabited for millennia by local people).

Since 2015, the team has thoroughly traversed the Cuito and Cuanavale Rivers. On this latest trip, they explored the source lakes of these two rivers and then headed westward to the Cubango River.

Source Material

The trip to the source lakes was particularly unique. Although the team had been there before, this was the first time they, or anyone else (at least as far as is known), would dive under the surface to view a hidden world.

“It is a system of source lakes, and we’ve now gained access to 12 of them,” says Boyes, describing how they had to create their own paths to get there. On this expedition, they rigorously explored three lakes.

The Cuito and Cuanavale Rivers are both fed by these lakes that in turn feed the Okavango Delta system. "It is a seepage system. Any water flowing off the surface is caught by the peat and released slowly. It is a very stable environment,” Boyes explains.

These lakes are surrounded by thick layers of peat that have accumulated over thousands of years, and remarkably, have remained mostly undisturbed. Elephants and hippos may have been using these source lakes before the Angolan Civil War, but it is clear they’ve not been there in a long time because the sediments are undisturbed.

The mission was to see what lies beneath the surface of these placid lakes, and what underwater species call it home. Adjany Costa, National Geographic Emerging Explorer and assistant director of the project, was surprised at some of the magnificent fish discovered on these dives.

NatGeo

NatGeo

“We found 96 species of fish there with four potentially new species just in the source lakes,” says Costa. She explains this biodiversity has been unexplored until now because the locals never even fish there for food—they believe the lakes and rivers are occupied by a snake-like monster that protects the aquatic habitat.

The otherworldly scenes of algae and fish serenely swimming were thus new to human eyes. Costa and Boyes both say they were surprised to see a goliath tigerfish swimming around in the Cuanavale source lake and expect more exciting finds to come as they analyze the wealth of data collected through sediment grabs, drones, and water sensors.

Rough and Wild

The Cubango River is quite different than the Cuito and the Cuanavale. It is harsh, rocky, and rough—and unlike the others, it has a well-traveled road to its west, which brings contact with people.

But, much like the 2015 expedition where Boyes almost got killed when a hippo flipped over his canoe, the Cubango River is still home to ornery hippos.

“We come around a corner in the boats, and this female starts charging us down,” Boyes says as he recounts his most recent encounter with a large female hippo—and her baby. After two days and no way around the two hippos, they had to call in the vehicles and go the long way around to avoid confrontation.

Besides just defining the biodiversity of the region, a main focus of the Cubango River expedition was to figure out how it is impacted by people living nearby. “We were counting every single dugout canoe. Every single person. Every single water pump.”

The team hopes these data will be used to prevent seasonal drying and overuse of the valuable Cubango waters that feed the Okavango system. “The only reason the Okavango Delta still exists is that this whole region was frozen in place for 27 years by the Angolan Civil War,” says Boyes.

Costa, a native of Angola, is dedicated to protecting the country she has grown to appreciate more as she has gotten older: “Ever since I started working with the project, it changed my perception of how I see Angola as a whole.”

The Okavango Wilderness Project will continue next year as they continue to explore new river systems in Angola and analyze the wealth of data they’ve collected.

“My father fought in a war in the place we are exploring right now,” Costa says, describing Angola’s far, wild reaches. “My whole notion of the Okavango and my connection with the area has completely changed.”

For the rest of this article please go to source link below.

Video can be accessed at source link below.