Biodiversity poorly protected by conservation areas worldwide

New research identifies gaps in the protection of biodiversity on Earth.

- The study identified the highest concentrations of species, phylogenetic and functional biodiversity on Earth and determined how well the current network of protected areas encompasses these dimensions.

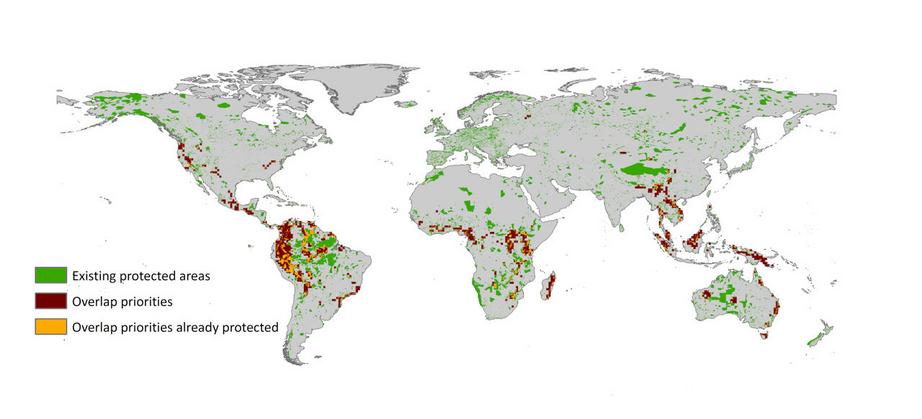

- The three facets of biodiversity overlap on only 4.6 percent of land on Earth, with only 1 percent under protection.

- The research points to areas that could be prioritized to maximize the amount of unique biodiversity protected.

Sorting out where to create parks, reserves and other protected areas typically involves looking for spots with high densities of different species of animals. But, according to a new global study, that approach falls short of safeguarding mammal biodiversity.

The research is part of a growing body of evidence highlighting the need for a broader view of biodiversity beyond how many species live in a specific area, one that takes into account the variety of evolutionary histories and the ways in which animals operate in an ecosystem. Known as “phylogenetic” and “functional” diversity, respectively, these biodiversity “dimensions,” along with the number of species, should be considered in effective conservation planning, said Fernanda Brum, a biologist at the Federal University of Goiás and the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, both in Brazil.

The overlap across areas important for species, phylogenetic, and functional biodiversity (brown), the current network of protected areas (green), and areas of overlap that are already protected (orange). Image and caption courtesy of Brum et al., 2017.

“When we are selecting areas based on species richness, we cannot assume that we are capturing those other things,” said Brum, the lead author of the study to be published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences.

“The current protected area networks are not located in the best places to capture those different dimensions,” she added.

Brum and her colleagues had been looking at the ways that humans influence phylogenetic and functional diversity, leading them to wonder if existing configurations of parks and other conservation areas served as citadels for the entire spectrum of biodiversity.

To answer that question, they mapped out the locations of these different facets of biodiversity. They pinpointed the habitats of more than 4,500 mammals. They also looked for the locations of 14 distinct mammalian traits – aspects of the mammals’ biology such as their diets, life spans and population densities that helped determine an animal’s functional role in the ecosystem.

For the evolutionary component, they scored the mammals on their relatedness to one another using phylogenetic “trees.” Animals located on branches farthest from others represent the greatest amount of unique evolutionary history.

An orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus) in Borneo. Photo by John C. Cannon.

They then compared the locations of the highest concentrations of the biodiversity dimensions, focusing on the top 17 percent for each. The 2011 meeting of the Convention of Biological Diversity in Aichi, Japan, set 17 percent as the goal for the area of the Earth to be protected by 2020.

Several regions had predictably high levels of all three types of biodiversity, such as the Amazon and Papua New Guinea. But globally, the team found that the priority areas for species, phylogenetic and functional diversity were largely distinct.

All three aspects overlapped on only 4.6 percent of the Earth’s surface, in fact.

“This is exactly what we would expect,” said Oliver Wearn, an ecologist at the Zoological Society of London who was not involved in the research. “The drivers of species richness, of phylogenetic uniqueness and of functional uniqueness are all different, so we would expect the patterns to be different.”

When the researchers compared these areas with the current set of protected areas according to the IUCN and the UN Environmental Program, the number was even lower. Only 1 percent of protected lands globally currently contain all three biodiversity facets.

“This result shows a challenge for conservation planning,” Brum said. “If you really want to capture as many facets of biodiversity as possible, how are we going to do it?”

These newly identified gaps in protected area coverage are one place to start, she said. With about 14 percent of global land area currently protected, the addition of the unprotected 3.6 percent could go a long way toward meeting that Aichi Target for protecting a full 17 percent of the Earth’s surface.

An African elephant (Loxodonta africana), pictured here in Tanzania. Photo by John C. Cannon.

“They accounted for the fact that you don’t want to conserve, for example, the same species, or the same functional space, twice,” Wearn said. “I don’t think all of this has been done together before.”

Now, the challenge is bringing in other critical considerations, he said.

“Incorporating the opportunity costs of establishing protected areas would be a major next step,” Wearn said, adding that it was important to identify spots in most urgent need of protection, such as the forests of Southeast Asia or Madagascar.

This study reflects just one aspect of determining which spaces to conserve, Brum said.

“The establishment of a protected area is more of a political decision than a biological decision,” she said. “You have socioeconomic issues, you have conflicts with economic activities, you need political willingness to protect the place, so it’s harder than just incorporating biological information.

“It’s just a starting map to look at those places, and see what’s going on there, why this is so important and what possible conflicts we might have in those places.”

For the rest of this article please go to source link below.

For full references please use source link below.