Will Madagascar lose its most iconic primate?

New research finds that ring-tailed lemurs are down to just a couple thousand individuals.

- Ring-tailed lemurs have suffered a drastic population decline in the last 15 years due to habitat destruction, hunting and live capture for the pet trade.

- The ring-tailed lemur is a ‘canary in the coal mine’ for Madagascar’s other lemur species, providing an urgent need for increased conservation capacity on the island.

- Ring-tailed lemurs could recover quickly if threats were removed, given their well-known adaptability.

One of the most iconic primate species on the planet is quickly disappearing. Once widely distributed across Madagascar, only 2,000-2,400 ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta) now remain in the wild, according to a new study published in Primate Conservation.

Conducted by Dr. Lisa Gould, professor of anthropology at the University of Victoria, and Dr. Michelle Sauther, professor of anthropology at the University of Colorado, Boulder, the study adds to an alarming chorus of research warning of catastrophic declines in ring-tailed lemur populations – research that until recently has been largely ignored by the media.

Observed as early as 1658 by Étienne de Flacourt, ring-tailed lemurs are one of the longest-studied and most intensely observed species of all primates.

“Michelle Sauther and I have both conducted research on ring-tailed lemurs at a number of sites in southern Madagascar since 1987, so that’s 60 years of research combined,” reflected Gould.

Juvenile ring-tailed lemur, L. catta, in gallery forest at Bezà Mahafaly Special Reserve, Madagascar. Photo Credit: M.L. Sauther.

Their most recent study utilized data from 34 sites where ring-tailed lemurs are currently known or were previously known to occur. The results are grim.

At 15 of the 34 sites, ring-tailed lemur populations have either become extirpated – meaning locally extinct – or are so small that they’re expected to vanish in the near future. Populations at 12 additional sites number fewer than 30 individuals.

Nowhere to hide

Scientists blame a variety of causes for the decline, including habitat destruction and fragmentation, live capture for the illegal pet trade, and hunting for the illegal bushmeat trade.

“The three factors are intertwined,” Gould explained. “As habitat is lost, hunting and live capture increase, and wild populations of lemurs become more accessible to hunters and to the illegal pet trade.”

Another recent study published in Folia Primatologica reports that ring-tailed lemur populations may have crashed by as much as 95% since the year 2000.

Equally alarming to the population declines is the fact that many of the remaining populations are restricted to relatively small forest fragments, isolating them from other populations. This prevents males from dispersing and could ultimately lead to damaging reductions in genetic diversity.

Long known as one of the most ecologically flexible of all lemur species, ring-tailed lemurs occupy a variety of habitats and are known for their ability to withstand considerable environmental pressures.

Given their recent declines, many researchers and conservationists are increasingly worried what this could mean for other lemur species in Madagascar with more specialized ecological needs.

“Ring-tailed lemurs are the proverbial ‘canary in a coal mine’ as they are so plastic and adaptable,” Sauther said.

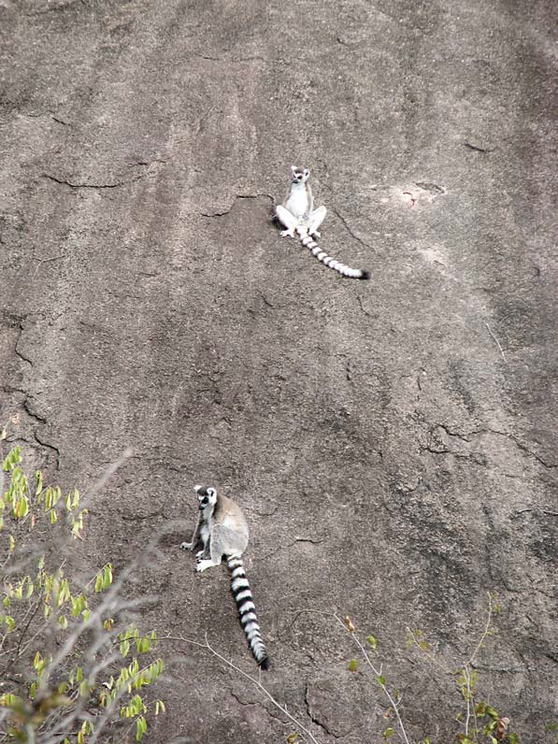

Ring-tailed lemurs at Bezà Mahafaly Special Reserve. Photo Credit: M.L. Sauther.

Gould added that “it would be much more difficult for more specialized lemurs,” such as the indri (Indri indri) and some species of sifaka (members of the Propithecus genus).

“We may witness some species extinctions in the near future, I am afraid.”

So how did such an easily recognizable and widely distributed species get to this point? To find out, let’s jump back in time.

Birth of a wild place

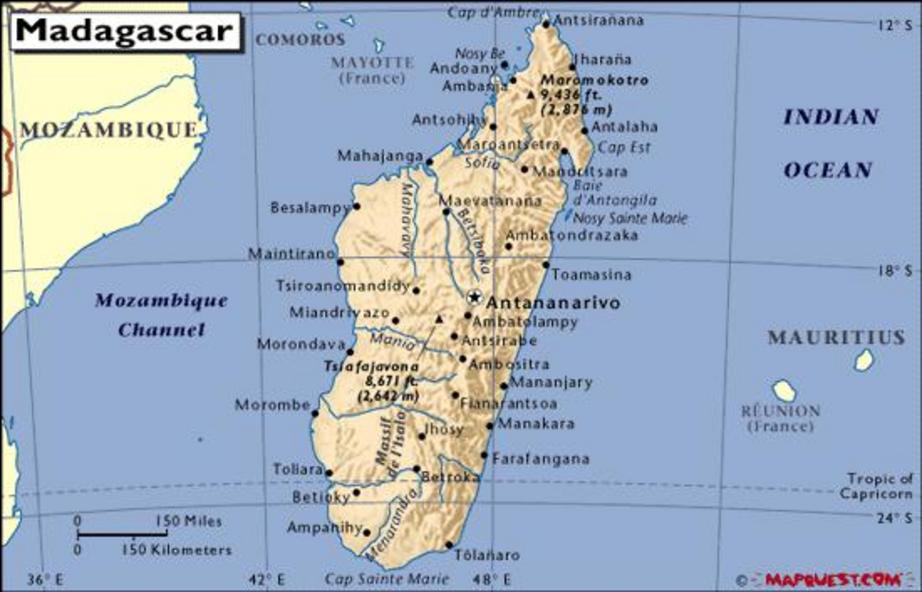

Situated roughly 250 miles off the southeastern coast of Africa, Madagascar is perched prominently in the Indian Ocean as the fourth largest island in the world. Following the ancient breakup of the prehistoric supercontinent known as Gondwana, Madagascar eventually split off from Africa, and later India, to become its own island some 88 million years ago.

Since then, its flora and fauna have remained free to evolve in isolation, resulting in extremely high levels of endemic species, meaning species which occur nowhere else on Earth.

Over 90% of Madagascar’s species are endemic, creating a sort of otherworldly zoo for anyone lucky enough to visit.

Unfortunately, far too many have visited over the years. Exactly when human settlement of the island began remains somewhat of a mystery. Many anthropologists contend that humans did not arrive until the middle of the first century CE, while others argue they were present far earlier. Regardless of when humans first arrived, all would agree that they’ve left their mark. Over 90% of the island’s original forest has been lost since the arrival of humans, and much of what remains is significantly degraded or fragmented.

According to Gould, there are currently thought to be 106 lemur species – including species and subspecies – all of which are considered endemic to the island. Many of these are now considered Vulnerable, Endangered, or Critically Endangered. And since the arrival of humans, who have come to be known as the Malagasy people, at least 17 lemur species have gone extinct.

This includes the bizarre giant lemurs, often divided into groups by paleontologists including the sloth lemurs, monkey lemurs, and koala lemurs. One sloth lemur, the Archaeoindris fontoynontii, reportedly weighed over 300 pounds, comparable in size to a male gorilla. Giant lemurs all disappeared over the last 2,000 years – and scientists believe humans played a significant role in wiping them out.

Ring-tailed lemurs at Tsimanampesotse queuing up to enter sleeping caves. Photo Credit: M. LaFleur.

“One of the key problems that no one seems to ever talk about, but which is at the heart of the ongoing threats to animal and ecosystem conservation, is the issue of human population numbers,” Sauther said. “With so many people placing such a strong stress on the ecology and economics of Madagascar, unless that is brought under control the situation will just get worse.”

Madagascar’s population today is thought to be over 25 million, 85 percent of which are estimated to live below the poverty level and depend on subsistence farming for survival.

An uncertain future

As a rising population struggles to provide for their needs, some researchers fear more forests will be cleared for agricultural practices such as cattle grazing and charcoal production. Ring-tailed lemurs have thus found themselves in an increasingly foreign world with fewer and fewer places left to eke out an existence, much less thrive.

“Of course forest and animal protection are the most important variables,” Gould said. “But local people must also want to preserve their forests and the animals within them.”

Ring-tailed lemurs on the rocky-outcrop forest fragments of the south-central highlands of Madagascar. Photo Credit: L. Gould.

Unfortunately, as more forests are cleared and access to previously intact forests increases, more animals are vulnerable to capture for the illegal pet trade or the bushmeat trade.

Gould explained that there are some conservation success stories to give hope to an otherwise ominous situation. Several reserves, such as Anja and Tsaranoro Community Reserves, empower local people to protect these animals and promote both social and economic development.

“These are run exclusively by local Malagasy conservation groups, and the local people involved benefit from tourism, which helps the local economy,” Gould wrote in an email. “There are also a few regions within Lemur catta’s geographic range where there are local taboos against harming/hunting lemurs, for example, Beza Mahafaly Reserve. However, local taboos can erode rapidly in areas where people from outside of the region move in and don’t hold the same beliefs and taboos.”

A road to recovery for ring-tailed lemurs, if it should happen, will be complex and riddled with obstacles. Support and protection from local conservation groups will be crucial, as will government enforcement of laws preventing poaching and the illegal wildlife trade.

Continued monitoring and observation of remaining populations will also be critical. In addition to this, Gould and her colleagues are discussing the possibility of utilizing new technologies, such as drones, to search in previously unsurveyed areas. For example, Tsimanampesotse National Park, a large protected area on the southwest coast, remains relatively unexplored, and could contain “remnant populations” of ring-tailed lemurs as well as other lemur species.

The good news is that this is an extremely adaptable species that has proved resilient through harsh droughts and natural disasters, as documented in a number of studies over the years. Given the proper conditions, recovery could happen quickly. Time will tell whether they’re allowed this chance – but there isn’t much time left.

As Gould and Sauther conclude in their new study, “Will we, in the next decade or two, lose the most recognized and iconic of all the lemur species?”