Tiger farms and illegal wildlife trade flourishing in Laos despite promise of a crackdown

‘Low-risk, extremely-high-return’ trade in endangered species’ body parts now ‘out of control’, says wildlife-crime expert

Laos, a landlocked country in Southeast Asia, has long held a key role in the global wildlife trade. Corruption and a flow of easy money across its porous borders have allowed the illegal trafficking of pangolins, helmeted hornbills and other wildlife products, as well as the country’s notorious tiger farms, to thrive.

A screengrab from Vietnam television (VTC Digital Television) showing a tiger being processed at a farm in Lak Sao, Laos.

Picture: Alex Hofford

In 2016, the Laos government told the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (Cites) in 2016 that it intended to shut down the tiger farms. However, a Post Magazine investigation has found the farms are flourishing, with another major operation having opened since the pledge was made. One expert described the trade in tiger parts used for medicines and potency treatments as “out of control”.

Foreign wildlife conservation groups working in the country say not a single arrest has been made for wildlife smuggling in Laos in recent years despite foreign aid for the training of rangers and to support investigations into smuggling syndicate kingpins.

“The rangers just take bribes from smugglers while officials take bigger bribes to allow the farms to keep operating,” a foreign wildlife-crime expert in Laos says.

A tiger farm in Lak Sao. Picture: Environmental Investigation Agency

Laos – ranked 135th alongside Papua New Guinea out of 180 countries and territories in a corruption index by Transparency International – has an estimated 700 tigers in farms and hundreds more smuggled from Thailand and other countries to be slaughtered and exported to China.

Less than two hours’ drive from the capital Vientiane, we find two of Laos’ biggest tiger farms operating as normal, with canvas sheeting covering their business signs the only visible concession to any supposed crackdown.

“There are more tigers in there than ever before – we hear their roars at night,” says a tea-stall holder working 200 metres from the Soukvannaseng tiger farm, in Bolikhamxay district.

- It is a low-risk, extremely-high-return business. If you are in the wildlife trade in Laos, you can literally make a killing

- Journalist and author, Julian Rademeyer

Figures given to Cites inspectors by the Laos government indicate the number of tigers held in the Soukvannaseng farm has more than doubled from 102 to 235 since 2016.

In nearby Houysiet village, we locate the home of trafficker Vixay Keosavang, whose syndicate is suspected of exporting thousands of tigers from Laos to China and Vietnam, along with illegal rhino horn and ivory.

The US government offered a US$1 million bounty in 2013 for information leading to the smashing of his syndicate, but Keosavang – known as the Pablo Escobar of the wildlife trade – remains at liberty. Neighbours say he drives a 4x4 and divides his time between opulent homes in Houysiet and Vientiane. “He is very rich and powerful and everyone here respects him,” says one.

There is no sign of Keosavang at his residence.

Investigative journalist and author Julian Rademeyer, who exposed Keosavang’s criminal network in his 2012 book Killing for Profit, says the illegal wildlife trade in Laos is flourishing because of the huge profits involved and rampant corruption.

“It is a low-risk, extremely-high-return business. If you are in the wildlife trade in Laos, you can literally make a killing,” he says. “It’s almost the perfect crime. Laos has the ideal climate for these kind of syndicates to fester and grow and entrench themselves, aided and abetted by official corruption.

“Vixay Keosavang was a man with senior government connections and cultivated those relationships over many years, and they clearly paid off.”

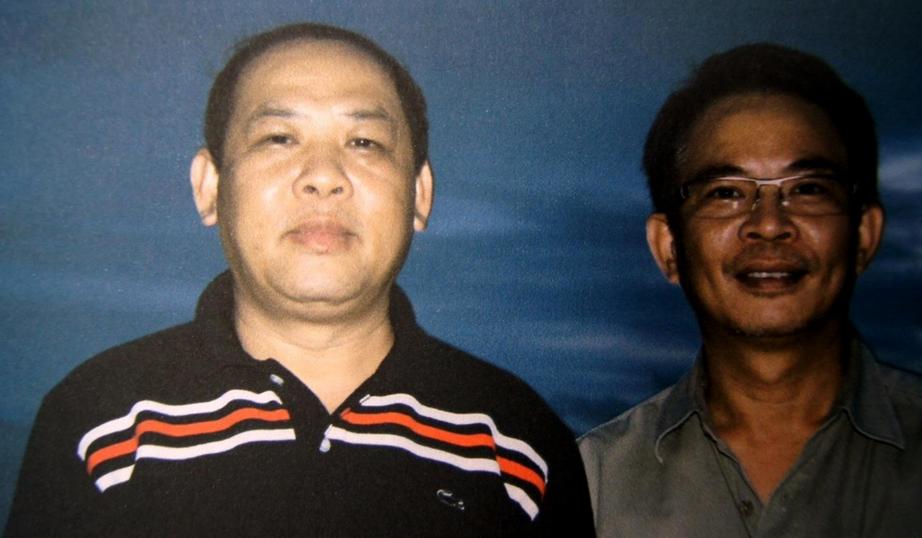

Trafficker Vixay Keosavang (left). Picture: Julian Rademeyer

In Vientiane, meanwhile, illegal wildlife products are widely available, including at a lobby shop at Don Chan Palace, a five-star hotel just a few hundred metres from the Presidential Palace and government buildings. Inside, we find bottles of tiger bone wine on sale for 1,650 yuan, packets of bear bile powder for 340 yuan and ivory bracelets for 400 yuan.

International donors have set up a fund to pay for an audit of tiger farms in Laos as a first step towards closing them but the government has blocked the initiative, which now appears doomed.

An official from an overseas conservation group involved in the project says: “I cannot imagine it happening as we have not even been allowed in to do preliminary inspection to plan for a full audit.”

Debbie Banks, the Environmental Investigation Agency’s campaign leader for Tigers & Wildlife Crime, has obtained drone footage of a new tiger farm opened near the Vietnam border.

“The Laos government is just stalling,” she says. “They are not taking action to do that audit. There has been no progress. The situation is completely out of control. There is no political will from the highest level to say ‘enough is enough.’”

Heather Sohl, WWF UK’s chief adviser for wildlife, says tiger farms in Laos need to be closed urgently.

“Poaching is one of the greatest threats faced by tigers,” she says. “Having tiger products from farms in the marketplace makes enforcement against those who trade in tigers poached from the wild all the more difficult.

“Laos has a chance to send a strong message to the world that trading in tigers is simply not acceptable.”