This toxic Australian plant injects scorpion-like venom

- the pain can last for days

Australia is home to some of the world’s most dangerous wildlife. Anyone who spends time outdoors in eastern Australia is wise to keep an eye out for snakes, spiders, swooping birds, crocodiles, deadly cone snails and tiny toxic jellyfish.

But what not everybody knows is that even some of the trees will get you.

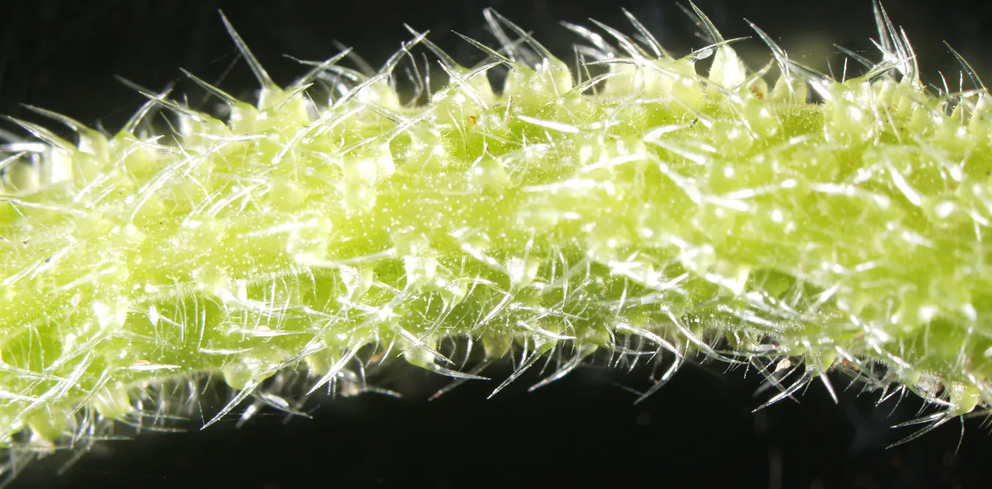

Our research on the venom of Australian stinging trees, found in the country’s northeast, shows these dangerous plants can inject unwary wanderers with chemicals much like those found in the stings of scorpions, spiders and cone snails.

The stinging trees

In the forests of eastern Australia there are a handful of nettle trees so noxious that signs are commonly placed where humans trample through their habitat. These trees are called gympie-gympie in the language of the Indigenous Gubbi Gubbi people, and Dendrocnide in botanical Latin (meaning “tree stinger”).

Join 130,000 people who subscribe to free evidence-based news.

A casual split-second touch on an arm by a leaf or stem is enough to induce pain for hours or days. In some cases the pain has been reported to last for weeks.

A gympie-gympie sting feels like fire at first, then subsides over hours to a pain reminiscent of having the affected body part caught in a slammed car door. A final stage called allodynia occurs for days after the sting, during which innocuous activities such as taking a shower or scratching the affected skin reignites the pain.

How do the trees cause pain?

Pain is an important sensation that tells us something is wrong or that something should be avoided. Pain also creates an enormous health burden with serious impacts on our quality of life and the economy, including secondary issues such as the opiate crisis.

For the rest of this article please go to source link below.