The science of plant intelligence takes root

For centuries, Western philosophy has viewed animals and plants as unthinking automatons. The famous 17th scientist and philosopher, Rene Descartes, maintained that non-human organisms cannot reason or feel pain; they are robotic machines that purely act on impulse.1

While science has recently proven that animals are intelligent creatures, capable of logical thinking and emotional experience, the notion that plants possess a similar kind of intelligence is largely disregarded by the scientific community. It is assumed that because plants do not possess a brain, they have no conscious experience.

Goethe and other thinkers through history observed that plants constitute an intelligent life-form, develop symbiotic relationships with other organisms, and can respond to complex changes in the environment. While the scientific community explains the intelligence of plant behaviour in terms of electrical and chemical responses to sensory stimuli, others believe that plants could provide a valuable insight into other forms of consciousness.

One of the most famous scientists to observe plant intelligence was the English naturalist, geologist and biologist, Charles Darwin.2 While Darwin is most prominently known for the theory of evolution, he was deeply fascinated by the behaviour of plants and made a valuable contribution to the botanical sciences. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Darwin maintained that plants are not unthinking automatons but highly complex and receptive organisms. In one of his last works, The Power of Movement in Plants, published in 1880, Darwin suggests that the root of the plant operates in a similar way to the neural networks found in lower animals, receiving information about the external environment and communicating it to other areas of its structure, writing:

“It is hardly an exaggeration to say that the tip of the radicle thus endowed (with sensitivity) and having the power of directing the movements of the adjoining parts, acts like the brain of one of the lower animals; the brain being seated within the anterior end of the body, receiving impressions from the sense-organs and directing the several movements.”3

Unfortunately, Darwin’s observations were rejected by leading scientists of the time, particularly the eminent plant physiologist Julius Sachs. He labelled Darwin an amateur scientist who performed careless experiments and acquired misleading results. However, in-depth analysis of plants is beginning to reveal they possess highly developed neural systems and even utilise the same neurotransmitters we do.

Modern Science & Plant Intelligence

While it is easy to dismiss these findings as pseudoscience, more and more scientists are recognising that plants exhibit brain like-functions and make sentient decisions. In 2009, researchers Dieter Volkmann, Stefano Mancuso, Peter W Barlow and Frantisek Baluska, published an article in the journal Plant Signal Behaviour entitled “The ‘root-brain’ hypothesis of Charles and Francis Darwin” in which they examined Darwin’s root hypothesis and whether current scientific literature supports his theory.

Based on complex analysis of scientific data, they concluded that “recent advances in chemical ecology reveal the astonishing complexity of higher plants as exemplified by the battery of volatile substances which they produce and sense in order to share information with other organisms about their physiological state.”4 According to the paper, plants can recognise self from non-self and roots, even secrete signalling exudates that “mediate kin recognition.” Moreover, plants are “capable of a type of plant-specific cognition, suggesting that communicative and identity re-cognition systems are used, as they are in animal and human societies, to improve the fitness of plants and so further their evolution.”

Darwin’s theories were ridiculed at the time he was writing, but now more open-minded scientists are discovering that plants may possess some form of conscious awareness, a discovery that would have pleased Darwin immensely.

Monica Gagliano delivered a keynote speech on Plant Intelligence and the Importance of Imagination in Science at the 2018 National Bioneers Conference in San Rafael, CA, USA.

Monica Gagliano delivered a keynote speech on Plant Intelligence and the Importance of Imagination in Science at the 2018 National Bioneers Conference in San Rafael, CA, USA.

One of the most interesting scientists to have undertaken research into plant intelligence is Monica Gagliano, associate professor at the University of Western Australia. In 2014, she conducted a series of experiments using Mimosa Pudicas plants to work out whether plants ‘memorise’ changes in their environment.

In order to test her hypothesis, she placed the plants in pots and then loaded each one onto a specially designed plant-dropping device. Each plant was dropped from a height of six inches, sixty times in a row at five second intervals. The plants would fall onto a soft foam to prevent them from bouncing, with the drop quick enough to cause the plants to curl up their leaves. Since the plants were not harmed in any way, Gagliano wondered whether they would eventually realise the drop did not signify an external danger. After a short amount of time, she found that “some individuals did not close their leaves when fully dropped.”The plants realised that falling from six inches would not cause them any harm and no longer curled their leaves.

Members of the scientific community were cynical of Gagliano’s findings, suggesting the plants merely became exhausted. Gagliano disproved this theory by taking a group of plants and placing them in a shaker in order to deplete them of energy. She found that the plants still curled their leaves, indicating they only became unguarded when dropped from a height to which they had become accustomed.5

Mimosa pudica is known as the ‘sensitive plant’, and appears to be able to learn from experience.

Mimosa pudica is known as the ‘sensitive plant’, and appears to be able to learn from experience.

Gagliano’s research has significant implications in terms how we see plants. The fact that they respond differently to situations that present no harm to those that do, implies plants recall sensory information and ‘memorise’ changes around them. While there is much uncertainty as to how plants recall this information, Gagliano believes it could be representative of a distributed intelligence operating entirely different to the mammalian brain.

This corresponds with Rupert Sheldrake’s ‘morphic resonance’ hypothesis that memories are not stored in the brain but in a universal informational field. We should imagine the brain to be like a television set which tunes into different programmes we watch, rather than a memory hard-drive. From this perspective, the brain has limited memory. Most of the information is stored somewhere else in some sort of ‘quantum database’. As Sheldrake points out, it has been proven that animals have memories that are engendered in other members of their species, and past experience is passed onto future generations. For example, in the United States cows learned about cattle grids and now farmers simply paint lines on the road to trick them from crossing. They seem to know what a cattle grid is even if they never seen one before. Examples like this suggest memory may not be an entirely neurological phenomenon but exists in other forms; this may explain why plants are able to memorise information without possessing a physical brain structure.6

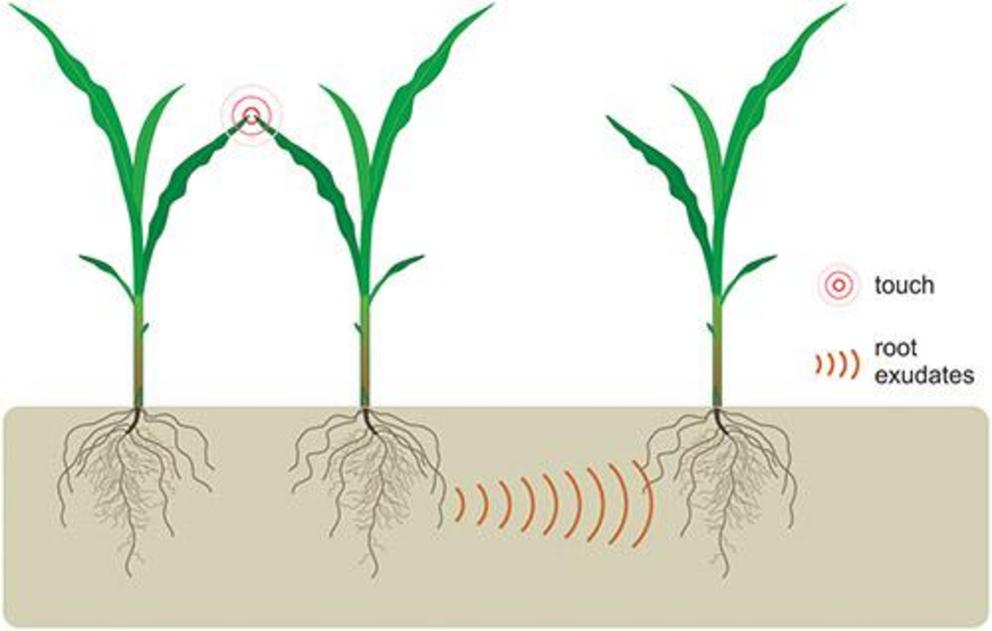

The notion that plants operate within a wider intelligence network is supported by recent experiments in plant communication. In a study conducted by Dr Velemir Ninkovic and his associate researchers at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, a soft brush was applied to corn seedlings, a stimulus that could represent different external stresses, such as new plants encroaching on their territory or an animal trying to eat it. New seedlings were then placed in the same soil as the recently touched plants to see whether it impacted their growth. The scientists discovered that the fresh seedlings responded by growing more leaves and fewer roots than the plants that had grown under unmodified conditions. This suggested that the corn seedlings were exposed to the chemical signals of the recently touched plants in the soil and therefore were preparing themselves against future stresses more effectively.7

Illustration of above ground interactions between neighbouring corn seedlings by light touch and their effect on below-ground communication.

Illustration of above ground interactions between neighbouring corn seedlings by light touch and their effect on below-ground communication.

In order to establish whether the plants were able to distinguish between the soil occupied by touched and untouched plants, the scientists offered corn seedlings the option of which medium they preferred growing in. When placed near both types of soil, the roots had a preference towards the growing solution that contained the untouched plants. These findings suggest that plants are able to communicate with each other even when they are not simultaneously present. This challenges the view that plants cannot exchange information in the way animals do and utilise complex communication networks to protect the interests of the group species. While science has historically depicted plants as inanimate and mechanical, in reality plants possess a profound ‘social’ intelligence that supports the continuation of their survival.

Plant Sentience in Shamanic Cultures

The belief that plants constitute an intelligent life form is commonplace in shamanic cultures, particularly those found in South America. As Michael Winkelman, Associate Professor at Arizona State University states, “the self-identifications with the broader universe, particularly personification of the sentient cosmos which is a hallmark of ecopsychology, is a fundamental aspect of shamanism.”

Religious ceremonies, practised for hundreds of years in these cultures, often involve the consumption of entheogenic plants to access alternative realities and altered states of consciousness. During these ceremonies, the shaman assumes the role of a spiritual guide to direct the experience through chanting, drumming, singing and other psycho-dramatic practices. The plants are believed to hold sacred properties, with the potential to provide the participant with profound insights.

Many people who have ingested Ayahuasca, an entheogenic brew made from the Banisteriopsis caapi vine in South America, report telepathic communication with plants, animals and people during the experience; the natural world becomes personified as an animated fractal intelligence that is constantly adapting, changing and evolving. Many also say the experience had a long-lasting impact on their connection with animals, people and nature, helping them solve their existential issues more effectively.8

In this sense, recent experiments into plant intelligence prove what shamanistic cultures have known all along – that plants are intelligent, sensitive and sentient life-forms.9 By observing their behaviour, we can learn more about the natural world and the complexity of all living things. Although modern science provided us with tremendous technological innovation and development, the reductionist belief that animals and plants are ‘mechanical’ in their nature, rather than a dynamic expression of intelligence and consciousness, has disconnected us from our environment and thus ourselves. As the independent scholar, author, teacher, and speaker on sacred plant medicine, Stephen Buhner, states:

Stephen Harrod Buhner

Stephen Harrod Buhner

“All people, and I mean all, know that the earth and everything in it is alive. Four-year-old children naturally know this. They have to be forcefully taught that the world is dead. Ancient and indigenous cultures never killed that sensibility but rather developed it. They were interwoven into the life web of the planet, not separate from it. But it was not only indigenous cultures but all ancient cultures that knew this, no matter how they developed… The thing that we call science has taken the long way around. And, they are now getting back to where we started long ago, aware that all of nature is alive, intelligent and aware. That we are merely one part of a very large living scenario.”10 (See my interview with Stephen Buhner in this issue.)

A Challenge to Outmoded Paradigms & Thinking

There are significant social, philosophical and religious implications for plant intelligence. It challenges the anthropocentric and monotheistic view that humans are the only species with a mind and a soul – we are not the most important entity in the universe but part of an interconnected web of life. There is great value in recognising nature’s extraordinary intelligence as we find ourselves on the brink of social, economic and environmental collapse. For decades, the capitalist economic model has depended on resources provided by non-human life forms in order to meet the needs of consumers. Perceiving plants as sentient life forms, rather than a mere resource for our consumerist habits, may prompt us to formulate new ways of living in harmony with the natural world. By expanding our view of how consciousness expresses, we can better appreciate the complexity of the ecological world and possibly halt the current path of environmental destruction. Buhner notes:

“The older, reductive, mechanistic paradigm that looked at the earth as a ball of non-sentient resources, we do with as we please, has reached its limits. It is destroying the ability of most life forms to endure, and the eco-systems of the planet. Younger and less mentally restrictive scientists in every field are finding that the world around us is far different than the picture that reductionists have created and taught us to believe. All life is intelligent, none of it is mechanical, and you cannot use the ecosystems of the planet as resources for unlimited extraction.”11

Plant intelligence also forces us to reconsider the nature of consciousness. Mainstream science currently posits the idea that consciousness is an epiphenomenon of the brain (it is generated by the brain). When we die, the brain ceases to operate, and consciousness switches off. In this reductionist perspective, plants and animals possess a very limited consciousness since their brains are not as neurologically complex. But the fact of the matter stands that modern science does not understand the mystery of consciousness and the process by which neural pathways, which are non-conscious, become self-aware as a complex web of connections in the brain. If plants have the ability to recall sensory information, socially communicate with each other, and respond to complex changes in the environment, we are forced to rethink our current models of consciousness. It may be the case that the human brain constitutes a very specific expression of consciousness, and intelligence manifests across a broad spectrum of life with plants possessing their own unique form of awareness which modern science does not currently understand.

To conclude, there is increasing evidence suggesting plants are an intelligent life-form. Recent scientific experiments indicate that plants are able to retain sensory information, respond to complex changes in their environment and even communicate with one another via complex biological networks. While we have yet to fully understand how plant intelligence works, these experiments challenge the orthodox scientific view that plants are non-sentient, and intelligence only emerges via neural pathways in the brain.

More free-thinking scientists and researchers are beginning to prove that plants possess brain-like functions and can make intelligent decisions, an idea accepted by shamanic societies for millennia.

There are significant philosophical implications for plant intelligence. Not only does it challenge reductionist explanations for consciousness but forces us to consider our treatment of the planet and agro-capitalism’s ongoing large-scale commodification of the plant kingdom.

As we teeter on the brink of environmental collapse, and traditional social, economic and political models become increasingly redundant and outmoded, it is critical we start perceiving nature and plants in a different light, rather than a depletable, capitalist resource.

For the rest of this article please go to source link below.