The accidental slaughter of millions of seahorses

Fishermen are wiping out seahorses that are caught in their nets as by-catch. Other less-charming fish might be sharing the same fate.

For fishermen in Malaysia, accidentally catching a seahorse is like getting a cash bonus. They can sell one of these tiny, odd-looking fish at the dock in exchange for roughly enough cash to buy a pack of cigarettes.

It’s not quite as lucrative as hauling in a prize tuna, but a seahorse is worth enough that fishermen can remember each time they caught one—which helped University of California, Santa Barbara, researcher Julia Lawson discover that millions more seahorses may be caught annually than make it into official reports.

Fishermen worldwide sold an annual average of 5.7 million seahorses from 2004 to 2011, according to the Convention on the International Trade of Endangered Species. Data from government agencies, surveys, and field interviews with fishermen that were conducted in 22 countries between 1989 and 2013, revealed to Lawson and her colleagues that the yearly number is probably closer to 37 million—more than a six-fold increase. The demand for seahorse is tied to its popularity in traditional medicine for treating virility problems.

“What struck us is [that] people were telling us, ‘I’m catching one [seahorse] a day; what does that matter?’” Lawson says. “But when you think of the scale of the fisheries, they’re extracting a huge number.”

What this means for seahorses is grave. Restrictions on their trade are already often ignored, and anecdotal evidence suggests population numbers are dropping. Yet Lawson thinks the bigger takeaway is what the rampant seahorse by-catch probably means for other small fish.

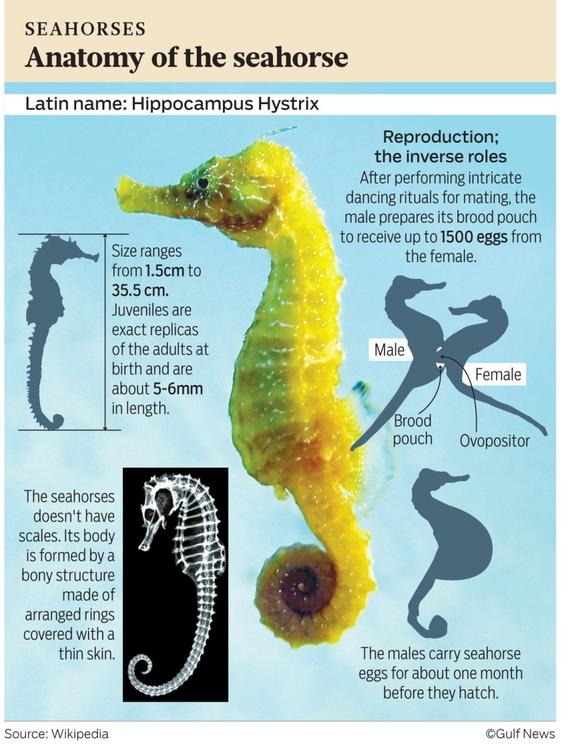

CC.wikipedia.org

Seahorses are a charismatic and easily identifiable species, and are more likely to stick out in fishermen’s minds. If the unintentional by-catch of seahorses can scale up to tens of millions every year, the same is probably true for other small, though less-memorable, fish species that occasionally turn up in nets.

“Most small fish just look like a grey fish, so they blend together in the minds of fishermen,” Lawson says. “Seahorses are potentially symbolic of a whole bunch of brown and silver fish nobody really pays attention to.”

Lawson will next investigate how to reduce small-fish by-catch in developing countries through community-based management. These regulation schemes often grant a group of fishermen exclusive access to an area, motivating them to take better care of it.

A researcher with the nonprofit Fish Forever, Gavin McDonald, says community-based management can help reduce small-fish by-catch, though the concept might initially be foreign to some fishermen. “In most of these countries, there’s not really a notion of by-catch—anything people fish, they’ll eat,” he says.

This means fishery laws that have effectively reduced by-catch in developed countries—such as quotas for certain species—probably wouldn’t work in places like Southeast Asia. The authors suggest that communities establish protected areas, as well as zones where non-selective gear, such as trawl nets, are banned.

Finding solutions will be a challenge, Lawson admits. “These people are often very poor, and they need to feed their kids. But we’re trying to find that balance to make the resources work for them.”