Slight bumps in protected areas could be a boon for biodiversity

A new study finds that small increases in the world’s protected lands could triple the protection of species and other types of biodiversity, potentially providing a new tool for conservation planners.

- Increasing protected areas by 5 percent in strategic locations could boost biodiversity protection by a factor of three.

- The study examined global protected areas and evaluated how well they safeguard species, functional and evolutionary biodiversity.

- More than a quarter of species live mostly outside protected areas.

- The new strategy from the research leverages the functional and evolutionary biodiversity found in certain spots and could help conservation planners pinpoint areas for protection that maximize all three types of biodiversity.

Sometimes small changes in the right place can make a big difference. That’s what a team of scientists found when they looked at how parks, sanctuaries and reserves might better protect the birds and mammals that inhabit them.

In a new study published Wednesday in the journal Nature, lead author Laura Pollock and her colleagues found that if we upped the land area under protection by just 5 percent in strategic locations, the number of safeguarded species could triple.

Research by Yale and the University of Grenoble documents where additional conservation efforts globally could most effectively support the safeguarding of species (some examples shown here) that are particularly distinct in their functions or their position in the family tree of life. Image and caption by Yale University/University of Grenoble

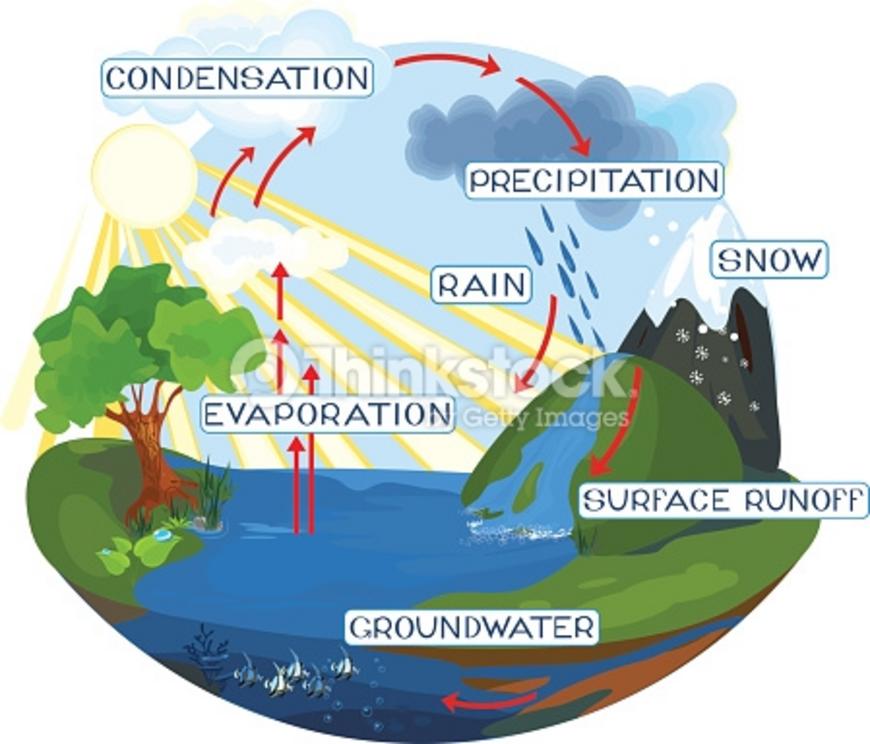

For their research, they mapped out the parts of the world currently under protection and tabulated the numbers of known mammal and bird species in those places. They also figured in the protection of two other “facets” of biodiversity – the functional roles that different animals play in their ecosystems and the amount of unique evolution, often measured in millions of years, that those animals represent.

Just like the number of species, both facets would be much better protected with that targeted 5 percent bump in conservation lands.

“Most conservation looks at species,” said Pollock, an ecologist at France’s Grenoble Alpes University, in an interview. The approach typically hinges on seeking out threatened areas that are hotspots of wildlife biodiversity and focusing energy on protecting them. Still, the researchers report, 26 percent of bird and mammal species don’t show up in most protected areas.

“Just targeting a biodiversity hotspot is not going to be the most efficient,” she said. “You’re potentially overlooking some really important species.”

They also found serious gaps in the protection of functional and evolutionary diversity.

A black rhino, which is listed as an EDGE species because of its unique evolutionary history and endangered status, pictured here in East Africa. Photo by Rhett A. Butler

The team looked at what would happen if they nudged the boundaries of protected areas to encompass carefully selected stretches of land important for those other facets of biodiversity. Pollock said she was “surprised” to see how much overlap there was between the three facets, “which means that you can choose some very key areas of the world, and you’re capturing a whole bunch of different types of diversity.”

And it’s not just about protecting animals for their own sake. “Those species are key to functioning ecosystems,” she added. Often, the “ecosystem services” they provide are critical for our own existence.

For example, birds might distribute seeds that contribute to the health of a carbon-siphoning forest. Or, hungry bats might keep pesky – and potentially disease-carrying – mosquito numbers low.

Some of these animals also represent millions of years of evolutionary history, which we only know because of the boom in genetic data that’s taken place recently.

“We would not have been able to do this analysis 10 years ago,” Pollock said.

Relatives of this echidna, related to the platypus, is a monotreme, a group that split from the rest of the mammals about 130 million years ago. Photo by Ester Inbar via Wikimedia

Species that harbor these exclusive genetic storehouses and that also face threats to their survival make the EDGE list, maintained by the Zoological Society of London. ‘EDGE’ is short for ‘evolutionarily distinct and globally endangered.’

Poster-species for conservation like the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) and the Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) are EDGE species. Topping the mammal list are spine-sporting echidnas (Zaglossus spp.). These egg-layers related to the platypus splintered away from the rest of us mammals on the tree of life a staggering 160 million years ago. Two of the three echidna species are classified as Critically Endangered by the IUCN.

Though they might escape the attention of most conservation efforts, Pollock said that such animals are “key to genetic diversity and our ancestral heritage,” and her research shows that protecting their homes might be beneficial to the diversity of life on Earth.

“The current set of protected areas is not located in an optimal way,” she said. “It could be much, much better.”

That doesn’t mean that Pollock wants to see current conservation plans to deal with the current biodiversity crisis scrapped, she said.

by Rhett A. Butler

by Rhett A. Butler

“It’s just saying, for a little bit extra, can we capture a few other species?” she said. “It’s admitting that we can’t do everything, but maybe we can tweak our current conservation based on this new information about what’s important to a global biodiversity pool.”

And while it might not be realistic to expect a 5-percent expansion in protected lands globally, their methods apply to smaller scales.

“You could still use the same approach,” Pollock said. Their data has just been added to the Map of Life website hosted by Yale University. Employing this approach at local levels could mean better-placed reserves and substantial gains in how much biodiversity they protect.

“You don’t need a tripling of biodiversity necessarily,” she added. “Ten percent more would be much better than what we have right now.”

For the rest of this article please go to source link below.

For full references please use source link below.