Scientists launch global search for 25 ‘lost’ species

Mongabay interviewed Robin Moore, communications director of Global Wildlife Conservation, to find out more about the Search for Lost Species campaign.

- The first phase of the this campaign, launched today by the Global Wildlife Conservation (GWC), will see groups of scientists spreading out across the world in search of "25 most wanted lost species".

- Collectively, these 25 species have not been seen in more than 1,500 years.

- The top 25 species include 10 mammals, three birds, three reptiles, two amphibians, three fish, one insect, one crustacean, one coral and one plant, found across 18 countries.

Unseen for decades in the wild, many species are now feared extinct. Some exist only as museum specimens, others are only known from old drawings or photographs.

But some of these missing species may still be out there, lurking in remote, unexplored regions of our planet. And to find them, scientists are embarking on what is believed to be the largest-ever global quest for our world’s forgotten animals and plants — the Search for Lost Species campaign.

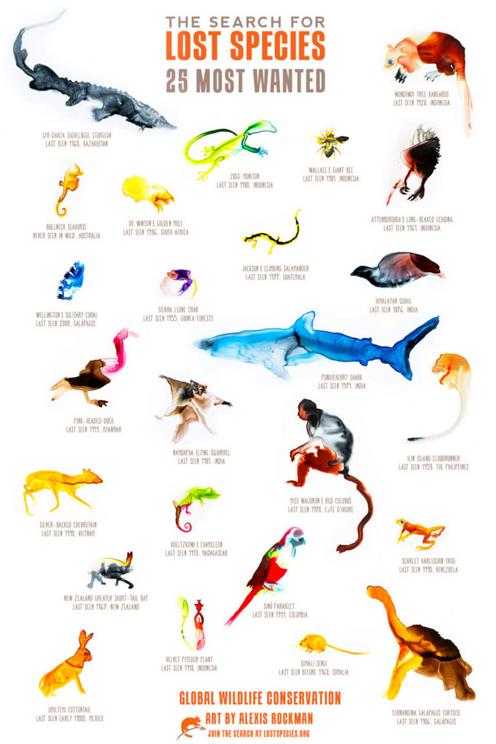

The Top 25 Lost Species. Poster by Global Wildlife Conservation (click on the image to enlarge).

The first phase of the this campaign, launched today by the Global Wildlife Conservation (GWC), will see groups of scientists spreading out across the world in search of “25 most wanted lost species”. These include the the tiny bullneck seahorse from Australia that has never been seen in the wild; the Himalayan quail that was last recorded 141 years ago in India; the Wondiwoi tree kangaroo, known only from a single specimen collected in 1928 in Indonesia; the pink-headed duck, once-widespread across India, Bangladesh and Myanmar, but last seen in 1949; and the Fernandina Galápagos tortoise, last seen in 1906 on the Galápagos’s youngest and least-explored island.

“These species include quirky, charismatic animals and plants that also represent tremendous opportunities for conservation,” Robin Moore, GWC communications director and conservation biologist, said in a statement. “While we’re not sure how many of our target species we’ll be able to find, for many of these forgotten species this is likely their last chance to be saved from extinction.”

The top 25 species in GWC’s long list of more than 1,200 lost animals and plants, include 10 mammals, three birds, three reptiles, two amphibians, three fish, one insect, one crustacean, one coral and one plant, distributed across 18 countries. Together, these 25 species have not been seen in more than 1,500 years, GWC said in the statement.

While some of these species are listed as critically endangered (and may even be possibly extinct) by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, others are listed as endangered, vulnerable or data deficient.

Mongabay interviewed Robin Moore, the brain behind the exciting Search for Lost Frogs initiative in 2010, to learn more about the Search for Lost Species campaign.

An interview with Robin Moore:

Mongabay: Why look for lost species? What do you hope to achieve?

Robin Moore: Put simply, to create flagships for conservation. To engage people in the protection of endangered species and critical habitats by raising the profile of some of the world’s forgotten species.

Rediscovery is such a powerful vehicle of hope — and hope is a much more powerful motivator than despair. I know I have gotten pretty used to talking to people about what we are losing, because I see it and live it every day, but we also need to be reminded that there is still an incredible, diverse world out there that is worth fighting for. I hope that by inviting people to join us on this quest — from its inception — we can rekindle those embers of curiosity and inspire people to connect with the wonder and awe of the natural world on a deeper level.

Pink headed duck. Photo courtesy of Global Wildlife Conservation.

Mongabay: How did you shortlist the 25 ‘most wanted’ lost species?

Robin Moore: We invited experts from over 100 Specialist Groups of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature to nominate candidate species. We took these nominations — over 1,200 species in total — and applied a number of criteria to determine the top 25 — a few of which are outlined below:

Firstly, we selected species representing a diversity of taxonomic groups — from mammals, birds and reptiles to corals, crustaceans and plants.

Secondly, we tried to achieve a good geographic spread to represent many of the biodiverse but imperiled habitats around the world.

Third, we assessed the likelihood that a species could be found. We took into account previous search effort and expert opinion on the added value of further searches. We omitted any species classified by the IUCN Red List as Extinct, instead focusing on species that are possibly extinct or simply too little known to gauge.

Fourth, we assessed the scientific and conservation importance of a rediscovery, reaching out to partners on the ground to assess possible follow-up conservation actions to protect the species and its habitat.

Finally, species with a compelling back story made strong candidates for the Top 25, because it is easier for people to connect with species whose story draws them in. It’s hard to overstate the power of a good story.

Mongabay: Why do mammals form the bulk of the top 25 species?

Robin Moore: Ten out of our Top 25 Lost Species are mammals, largely because we had fuller back stories on many of these species, which helped elevate them to candidates for poster species of the campaign. People generally connect more easily with mammals than they do with species further away from us on the evolutionary tree. There is a reason that most flagships for conservation are large-bodied mammals. But we want to use the “charisma” of a lost colobus monkey and tree kangaroo to draw people in, and to learn more about the Sierra Leone Crab, Wellington’s Solitary Coral, and Velvet Pitcher Plant, for instance. But we have to get our foot in the door with people’s attention first.

The Namdapha flying squirrel is known only from a single specimen collected in Namdapha National Park in 1981. Photo from Zoological Survey of India (CC BY-SA 3.0).

Mongabay: How does the campaign work with local partners? How many scientists and organizations are likely to be involved in this?

Robin Moore: We have collaborated with more than 100 scientists and conservation partners around the world to compile the list and develop searches. Our aim is to make this a truly collaborative campaign, and to work with as many local partners as possible, as this is our model at Global Wildlife Conservation. Our aim is to establish long-term partnerships that will lead to the protection of these species and their habitats. We also want to engage people beyond our conservation and scientific partners in the search, and have created a project within iNaturalist so that anyone can submit observations of lost species. We also invite people to nominate lost species that may be missing from our list.

Mongabay: How do you fund such an expansive search?

Robin Moore: Creatively! We will be adopting a number of approaches to raise the funds for expeditions, from an auction of lost species artwork by renowned artists, to enticing individuals and companies to sponsor expeditions, to crowdfunding.

A live bullneck seahorse has never been seen in the wild. Image by Sara A. Lourie.

Mongabay: Shouldn’t we be focusing our efforts and funds on saving species that we know are out there and are imperiled?

Robin Moore: We definitely should. But it is also not a zero sum game. One of the primary goals of this campaign is to raise support for conservation that would otherwise not be available, by inspiring people to become engaged in the cause.

Global Wildlife Conservation has worked with partners around the world to create more than 20 new nature reserves, home to more than 100 threatened species. And we continue to do this important work. But there is a reason I am being asked about this campaign instead — it taps into something very different inside of us. It is a promise to bring people with us on an odyssey of exploration and discovery to uncharted lost worlds, to feel the tingle of excitement at the first glimpse of an animal that has not been sighted in 100 years, and never before photographed.

Mongabay referred to our Search for Lost Frogs as “one of conservation’s most exciting expeditions”. It is this excitement that I think we need to connect with more deeply, as this is what we feel when we first fell in love with the natural world, and it is what is going to inspire a new generation of conservationists. We are also tapping into our innate tendency to value more what we have lost than what is right in front of us to create novel flagships for conservation and inspire action.

It’s important to note that species rediscoveries often result in conservation efforts that benefit not just the species but also their habitats and other wildlife. Take the Jamaican Iguana — after four decades without trace it was rediscovered and brought back from the brink of extinction by an international consortium — it is now a flagship for the conservation of an imperiled dry forest habitat in Jamaica.

Mongabay: What are some of the hurdles you foresee in your search?

Robin Moore: Many of the places in which these species live are extremely remote, and the species themselves are elusive and poorly known. Take the Bullneck Seahorse — it has never been seen in the wild, and so it is unclear exactly where to target a search. Also, as we discovered during the Search for Lost Frogs, the weather does not always cooperate with the best laid plans, and in one instance torrential rains and mudslides forced a team back before they really got going. It’s hard to plan to find something that hasn’t been seen for 100+ years — but if it weren’t so challenging, it wouldn’t all be so tantalizing.

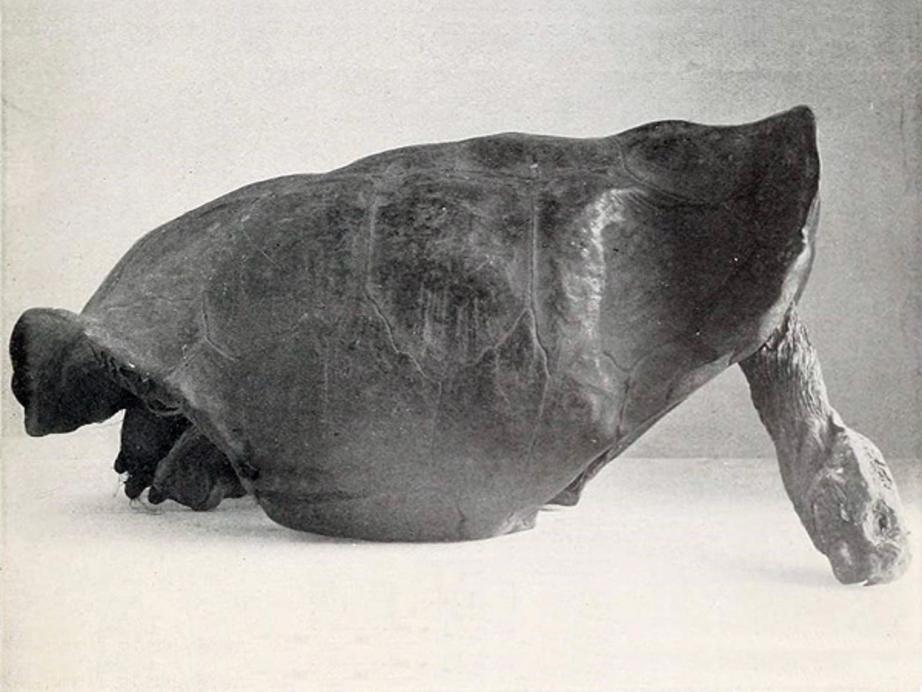

Fernandina Galápagos tortoise was last seen alive in 1906 on the Galápagos’s youngest and least-explored island. Image by John Van Denburgh courtesy of Global Wildlife Conservation.

The Himalayan quail was last seen 141 years ago in India. Photo from ARKive of the Himalayan quail (Ophrysia superciliosa)