Scientists have grown snake venom glands in the lab. Here's why that's awesome

For the first time, scientists have produced snake venom toxins in the lab, opening up a much-needed path for developing drugs and venom antidotes that doesn't involve having to breed and milk real-life snakes.

The toxins have been produced through mini glands called organoids, following a process adapted from growing simplified human organs – something that is already helping in a wide range of scientific and medical research projects.

In the case of the snakes, researchers were able to blow organoids matching the Cape coral snake (Aspidelaps lubricus cowlesi) and seven other snake species, and they say this new approach is a welcome upgrade on current methods of farming snakes to extract their venom.

"More than 100,000 people die from snake bites every year, mostly in developing countries," says molecular biologist Hans Clevers, from Utrecht University in the Netherlands. "Yet the methods for manufacturing antivenom haven't changed since the 19th century."

By tweaking the recently developed process for growing human organoids – including reducing the temperature to match reptiles rather than mammals – the researchers were able to find a recipe that supports the indefinite growth of tiny snake venom glands.

Tissue was removed from snake embryos and put into a gel mixed with growth factors, but access to stem cells – which is how human and mouse organoids are usually developed – wasn't required.

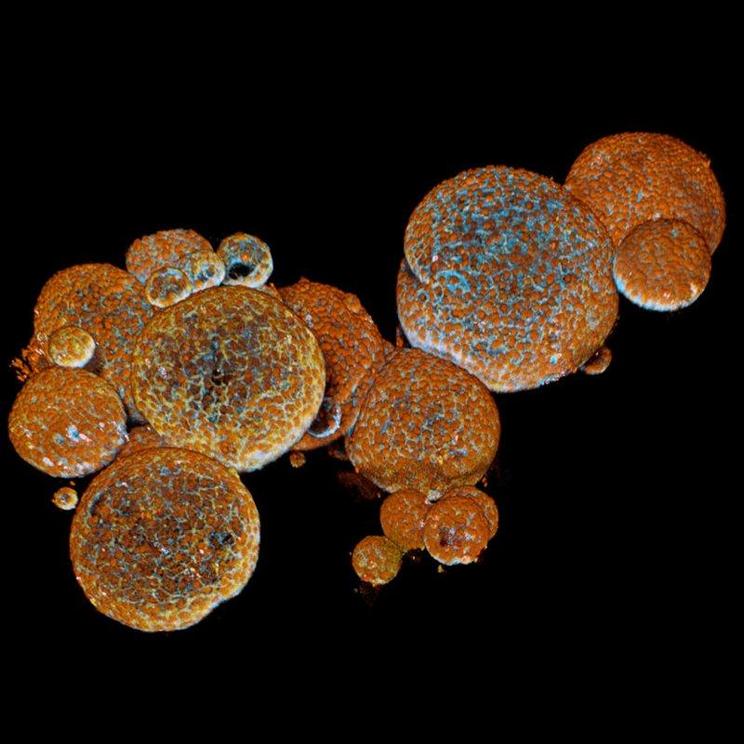

The cells quickly began dividing and forming structures, giving the team hundreds of growing samples in the space of a couple of months, and producing small white blobs from which venom toxins could be harvested.

Al least four distinct types of cell were identified by the researchers within the artificially grown venom glands, and they were also able to confirm that the venom peptides produced were biologically active, closely resembling those in live snake venom.

Snake venom gland organoids.

Snake venom gland organoids.

"We know from other secretory systems such as the pancreas and intestine that specialised cell types make subsets of hormones," says developmental biologist Joep Beumer from Utrecht University.

"Now we saw for the first time that this is also the case for the toxins produced by snake venom gland cells."

The use of snake venom toxins to develop medicines and treatments has been going on since the time of ancient Greece. In the modern age, drugs fighting everything from cancer to haemorrhages have been developed with the help of toxins we find in snake venom.

Having faster and more controlled access to these toxins could mean these treatments can be developed more easily and on a shorter time scale, say the researchers.

Besides drug development, these organoid venom glands should make it easier and faster to develop antivenoms – and with so many people suffering deaths, injuries or disabilities because of snake bites, that will make a considerable difference.

"It's a breakthrough," snake venom toxicologist José María Gutiérrez from the University of Costa Rica, told Science.

"This work opens the possibilities for studying the cellular biology of venom-secreting cells at a very fine level, which has not been possible in the past."

The research has been published in Cell.