It's banned in other countries but New Zealand is using more toxic methyl bromide than ever

NZ is a world leader in the use of the toxic gas methyl bromide

Methyl bromide, an ozone depleting toxic gas harmful to humans, is banned in many countries but New Zealand is using more than ever. In part one of a three-part investigation, Tony Wall speaks to people who've faced pressure to keep quiet about the issue.

Every few minutes, a logging truck rumbles through the gates at the Port of Tauranga. More logs arrive by train.

The wharves at Mount Maunganui are covered in huge stacks - there are so many logs they've had to store them in a yard nearby.

All this wood - 5.5 million tonnes of timber went through the port last year - has brought jobs and industry to the area. It's also brought methyl bromide. Loads of it.

The gas is an extremely effective killer of all organisms and is used in small quantities to fumigate imported fruit, vegetables and other products. But by far the biggest users are timber exporters.

In 2016, 220 tonnes of the toxic, ozone-depleting gas was administered to logs at the Port of Tauranga to kill insects prior to export.

Another 250 tonnes was used at Northport near Whangarei and 70 tonnes at Napier Port - making New Zealand the world's fifth biggest user of methyl bromide and by far the biggest per capita.

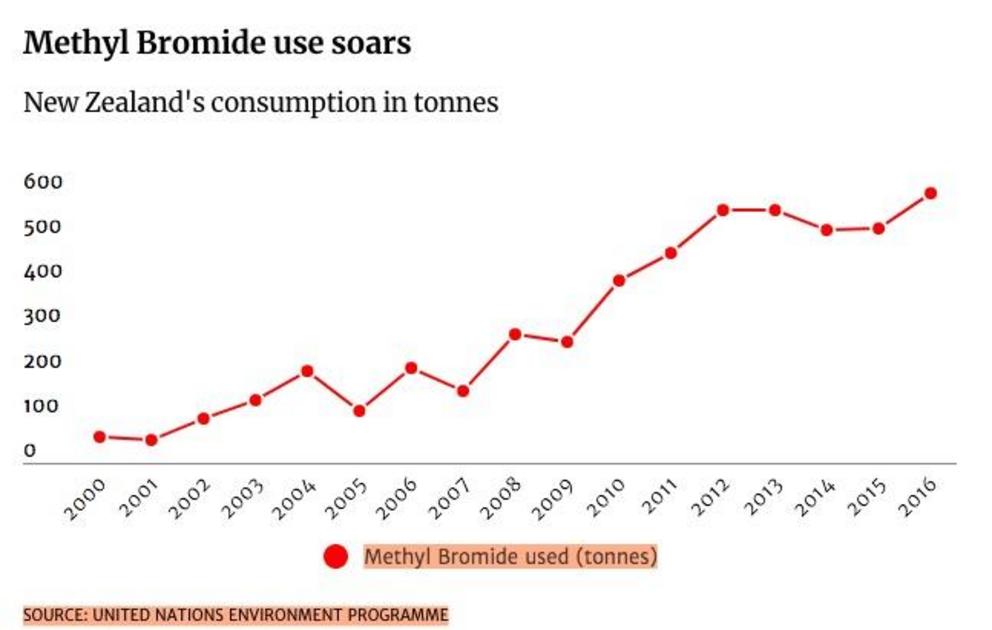

Our consumption of the fumigant has rocketed from less than 100 tonnes in the early 2000s to around 600 tonnes today, mirroring a timber boom - log exports have tripled since 2008 and are now worth $2.7 billion.

Matthew Carratu couldn't believe it when he took his young son Alex, who was recovering from cancer, sailing at the Tauranga Yacht Club at Sulphur Point and noticed container fumigations were happening just over the fence.

"It was so close it was just ridiculous," Carratu, an osteopath, says. "I come from the UK where methyl bromide is banned. The fact that this 'pure, green, 100 per cent place' that we came to for a utopian experience does daft things like that is anathema."

Aubrey Wilkinson, a crane operator at the port and spokesman for the Tauranga Moana Fumigant Action Group, which aims to have methyl bromide eliminated or at least contained to a purpose-built facility, says the community has been slow to react.

"I know down in Nelson there were huge campaigns and the community got behind it and battled the local council and the port.

"I don't think the community here was aware of what was happening over the fence, within the port. It makes me angry and something needs to be done about it."

CHRISTEL YARDLEY/STUFF

Aubrey Wilkinson of the Tauranga Moana Fumigant Action Group says port workers are concerned they're being exposed to methyl bromide.

DEADLINE LOOMS

Methyl bromide was used for decades as a soil fumigant for crops like strawberries and potatoes but under the Montreal Protocol aimed at protecting the ozone layer, it had to be phased out for all but quarantine purposes by 2005.

Countries are required to reduce its use and some, including those in the European Union, have banned it altogether.

That's not such a big deal for countries that export processed timber which doesn't need treating.

But New Zealand mostly exports raw logs and two of its biggest markets, India and China, insist they be treated with methyl bromide.

(China also accepts logs fumigated with phosphine, which has helped exporters reduce methyl bromide use.)

In 2010, the Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) mandated that methyl bromide be recaptured and destroyed for all fumigations in New Zealand by October, 2020.

The timber industry and Genera, the fumigation company which does most of the log fumigations in New Zealand, have spent millions trying to develop recapture systems that can deal with the scale required for log stacks, with limited success.

It's feared the 2020 deadline will be missed - already the industry is preparing an application to have the rules around methyl bromide reassessed.

"I've just about got a clock on my wall heading to doomsday," says Don Hammond, chair of forestry industry group Stimbr (Stakeholders In Methyl Bromide Reduction).

But the fact is, he says, technology to fully recapture methyl bromide emissions from log stacks doesn't exist.

"We're desperate to find a solution. We're investing as much as we possibly can into finding a way out of this."

Chrystel Yardley

Workers at the Port of Tauranga vent methyl bromide from a log stack.

INVISIBLE THREAT

Methyl bromide is colourless and odourless so people don't know if they've been exposed. It's heavier than air and can accumulate in poorly ventilated or low lying areas.

According to the Ministry for Primary Industries, a single, small exposure is unlikely to cause long-term effects.

But exposure to high concentrations can cause damage to the lungs and nervous system or even death.

There's a lack of research on the effects of long-term exposure to small amounts of the gas, but it's been suspected in a number of cases of motor neuron disease in Nelson port workers and associated with some cancers.

Methyl bromide can be recaptured and destroyed when used to fumigate containers but with log stacks it's pumped under tarpaulins and mostly vented to the atmosphere after about 24 hours.

Tauranga locals are concerned that when the gas is vented, or if a tarpaulin rips in high winds as occasionally happens, invisible plumes of gas could drift across the port and surrounding areas, affecting residents, workers, boaties, cruise ship visitors and a nearby marae.

Four port workers were taken to hospital in March after feeling dizzy and nauseous. Fumigation had been going on nearby but it's still unclear if it was to blame; it's understood blood tests didn't show elevated methyl bromide levels.

A Bay of Plenty Regional Council investigator is continuing to review evidence, including video taken by a port worker showing the venting that was going on.

One of the stevedores who went to hospital claims it's not the first time workers have been exposed - "it's a common event" - and says some colleagues have refused to work when methyl bromide is being vented.

"They just don't come out of their huts if they're de-tarping."

The worker says he wants to speak out but has been "muzzled".

"If you don't do what you're told you get removed off the board and they don't give you work."

CHRISTEL YARDLEY/STUFF

The Tauranga Moana Fumigant Action Group is fighting to eliminate or drastically reduce methyl bromide at the port.

There have been no recorded instances of methyl bromide exceeding allowable levels at the port, but the fumigant action group says the plume could drift above monitoring equipment anyway.

Genera, which holds the consent to discharge methyl bromide, says independent studies have shown port workers are exposed to lower levels of methyl bromide than other toxicants at the port, and the gas is not as toxic as some other substances.

But the Environment Court has expressed concern, saying in a decision last year dealing with an application by another company to use methyl bromide at the port that discharge limits have been exceeded on many occasions and noting there were problems with monitoring.

"At this stage, we can express no confidence that the current use of methyl bromide at the port is meeting the standards set by the EPA," the court said.

Several people approached by Stuff declined to comment or wanted their names withheld for fear of damaging relations with the port, one of the area's biggest employers.

Carratu says he was surprised by the attitude of locals when he raised concerns about the proximity of fumigations to children and families. A sailing coach took umbrage.

"That confused the hell out of me. He talked about the amount the club benefits financially from the port and in shared use of infrastructure - how they couldn't do what they do without it."

Carratu says he got a better response from the club when he emailed asking why there was no warning when fumigations were to happen - "they said they'd look into it".

The regional council found Genera was complying with the 25m buffer zone required for container fumigations but signage was inadequate. A formal warning was issued.

But Carratu hasn't been back since. "I'm not putting my children at risk of that stuff."

This map, developed by air quality modeller Ausplume and using a year's worth of weather data, shows how gas might disperse over Tauranga based on a 24-hour average if 10 log stacks were fumigated at once. It is theoretical. The numbers are milligrams per cubic metre. The exposure limit for the general public for methyl bromide is 1.3mg/m3.

'BANNED FROM THE PORT'

Anna Woolfrey is another British immigrant who raised concerns about methyl bromide at the port.

Woolfrey was working as an environment, health and safety specialist for stevedore company C3 in 2016 when she became aware that workers were concerned they weren't being notified about fumigations, according to a source familiar with events.

Woolfrey sent several emails to the port's health and safety team on a number of issues including methyl bromide, but according to the source, nothing was done.

She had resigned from her job but was working out a notice period when she sent her final email, the source says.

"She got a text the next day to say she was banned from the port, even though she had about a month left to go of her notice."

C3 asked her to sign a non-disclosure agreement - Woolfrey says she can't comment because of it.

Dan Kneebone, the port's property and infrastructure manager, says Woolfrey's port access card was cancelled when her employment was terminated, which is standard.

C3 boss Parke Pittar says he can't discuss past employees, but insists the company encourages staff to report any concerns.

"We respect their right to speak out about environmental, health and safety issues and encourage their ideas and suggestions for improvement."

Kneebone too says the port has no problem with people talking about methyl bromide, and notes the company gave the action group a tour of the port to help them better understand the issue and listen to their feedback.

Fumigation is a complex issue with no easy solution, he says. The port maintains dialogue with major port users and provides information about methyl bromide to all visitors during safety inductions.

Kneebone says risk management is shared across all the employers involved "and we take our responsibilities as a landlord very seriously".

AD HOC APPROACH

While the EPA sets national regulations, the methyl bromide problem has been dealt with in an ad hoc way around the country.

In places like Picton, Nelson and Wellington its use was restricted after public campaigns; in Auckland the port has taken the lead by requiring all emissions be recaptured; in Northland and Hawke's Bay the regional councils don't even require operators to have a resource consent.

Most recent data for methyl bromide use

In Tauranga, the regional council has been accused of taking a soft approach because it's the majority owner of the port. The fumigant action group accuses it of putting economic considerations ahead of "enforcing environmental bottom lines".

The environment court echoed this view, saying the council's shareholding "must raise concerns for transparency and independent monitoring".

But Sam Weiss, the council's senior regulatory officer, says the council has gone "above and beyond" the EPA by requiring that Genera be using recapture technology for all fumigations 18 months ahead of the EPA deadline.

The recapture targets have been staggered and twice Genera has had deadlines extended after failing to meet them.

The extensions were granted on a non-notified basis, which angered the action group.

"The Port of Tauranga is one of the largest methyl bromide users in the world, and our community doesn't get to engage and have a public process around that use - it's all being dealt with through non-notified variations - that astounds me," says Kate Barry-Piceno, an environmental lawyer who has advised the action group.

Genera's consent had required it to be using recapture technology for 60 per cent of its timber fumigations by June 1 this year, but in April it applied for that deadline to be pushed out by a year.

The action group demanded to be heard and said in a submission that approving the application would make a mockery of the consent conditions.

"It would send a continued message that the council is willing to allow environmental damage to our ozone layer and that communities' wellbeing plays a sad second best to the...council's economic growth drive," the submission said.

In the end, the council gave Genera a six-month extension to reach the target and said it could apply at any time for further changes.

Kent Blechynden/Stuff

A protest against methyl bromide use at Centreport in Wellington was held in 2008.

Ironically, Genera is just as unhappy with the council - chief executive Mark Self says its staff are constantly raising "trivial" issues such as signage instead of letting the company get on with research into recapture technology and alternative fumigants.

"They seem to be into trivial policing rather than the big picture."

Weiss says: "If we're being criticised equally from all sides it probably shows we're charting about the right course."

He says the council has issued Genera with four abatement notices in the past two years: for insufficient notification in advance of a ship fumigation, not meeting a recapture target, fumigating too close to the port boundary and not meeting signage requirements.

Meanwhile various groups are firing shots across the bow of industry and regulators.

In January, the Rail and Maritime Transport Union wrote to the port accusing it of not complying with its health and safety obligations - arguing it "cannot be certain on reasonable grounds" that methyl bromide emissions are within allowable limits because monitoring is inadequate.

The port responded by saying while it has some responsibilities, companies which engage Genera to do fumigations have the primary duty of care.

Doug Leeder, who is chairman of the regional council and also a port director, rejects any suggestion that the port is washing its hands of the problem.

As fumigations happen on the port's land, it has a responsibility as a "good landlord and citizen" to ensure the requirements of the consent are complied with, he says.

And Leeder says it's "nonsense" that the council is taking a soft approach because of its ownership of the port.

If anything, he says, the consent and compliance staff focus more closely on the port because of the perceived bias. Independent commissioners have been used to make recommendations on the Genera consent, Leeder says.

Tony Wall

Lawyer Kate Barry-Piceno says the public should have more say in the use of methyl bromide.

But Barry-Piceno, the environment lawyer who has advised the action group, says the council's actions over the application by a Genera rival, Envirofume, for a resource consent to discharge methyl bromide shows where its priorities lie.

An independent commissioner had rejected the application, but when Envirofume appealed to the Environment Court the council switched positions, supporting the application after Envirofume made amendments.

"That's quite an unusual position for a regional council that is usually very strong on aspects of environmental pollution."

The court rejected Envirofume's appeal.

Barry-Piceno says the concern is that the council will continue to allow Genera to vary its conditions and push out the recapture targets.

"You can only point to how other developed countries are dealing with the same level of risk," she says. "And that's not how it's being managed down there at the port."

For full references please use source link below.

Video can be accessed at source link below.