Is a water war about to break out along the Nile?

Two of the world’s most ancient civilizations remain at loggerheads over access to water, a dispute that could presage conflicts to come on an increasingly thirsty and electricity-dependent planet.

Ethiopian Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn rejected an Egyptian proposal over the weekend to have technical disagreements over construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) addressed through arbitration by the World Bank.

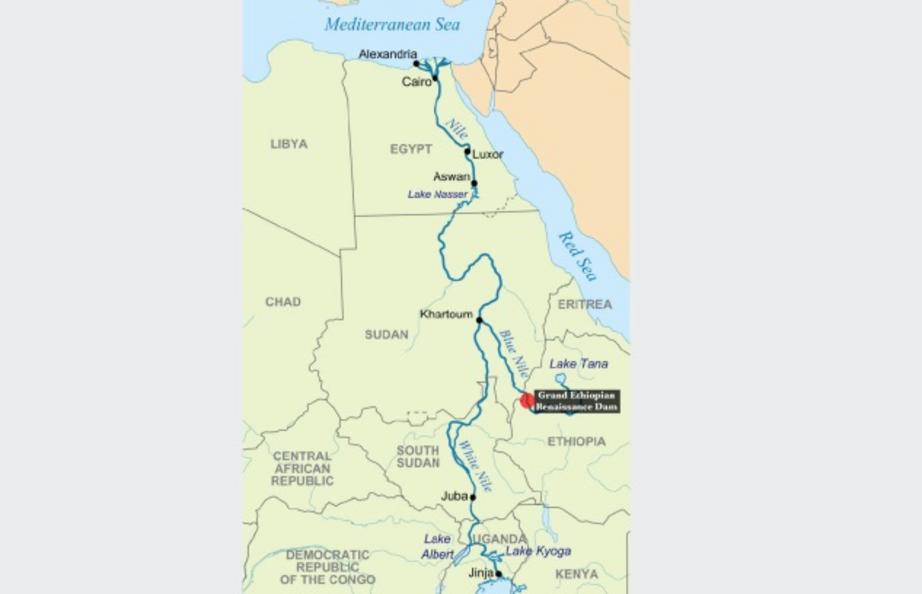

Egypt worries that, when completed early next year, the hydroelectric dam being built 2,000 miles upriver will siphon water it uses from the Nile River, water that has flowed from Ethiopia down through the deserts of Sudan and into its fields and reservoirs.

Ethiopia claims the $4.2 billion project, soon to be the largest dam in Africa, is essential to its economic development and has sought to reassure Egypt that it will be used only for energy creation. But rhetoric from Cairo has been less than accommodating.

“No one can touch Egypt’s share of water,” said Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi last November. “We view positively the developmental needs of our friends and brothers in Ethiopia, but we are capable of protecting our national security, and water to us is a question of national security. Full stop.”

The Egyptian government has publicly ruled out military action, but earlier this month Sudan abruptly recalled its ambassador and officially warned Egypt of threats to its eastern border from massing Egyptian and Eritrean troops.

The Rain in Egypt Falls Mainly in Ethiopia

Egypt is one of the most water-dependent countries in world. Roughly 97 percent of its freshwater falls as rain outside its borders. It has very little groundwater and receives little rainfall. It is one of the driest, sunniest countries in the world.

“They were already facing serious water problems even without the GERD dam,” said Michele Dunne, director of the Middle East Program at Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Almost two-thirds of Egypt’s water originates in the Ethiopian Highlands along the Blue Nile, one of the Nile River’s two main tributaries. The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam is being built on the Blue Nile.

Dunne said the Nile provides basically all of Egypt’s fresh water supply, 85 percent of which is swallowed up for agriculture along the fertile Nile Delta.

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam is being built 2000 miles upriver from Cairo, on the Ethiopia-Sudan border on the Blue Nile.

Courtesy: Yale Environment 360

“And most of that is flood irrigation, which is very wasteful,” notes Dunne. “You’re losing a great deal of water to evaporation. They need to switch over to drip irrigation, but have resisted and delayed for years.”

Dunne said that over the decades Egypt has come to rely on the under-use of water by other Nile Basin countries, such as Sudan, Ethiopia, and Uganda, because of low levels of economic development in those areas.

As it stands, Egypt already has one of the lowest per capita water shares in the world, where people consume just 660 cubic meters per year (compared to 2,842 cubic meters for the U.S.)

“And with a population expected to double in the next 50 years, Egypt is projected to reach a state of serious country-wide fresh water and energy shortage by 2025,” according to a 2017 study published by the Geological Society of America.

Colonial Legacy

Historically, Egypt has received the lion’s share of Nile waters: About 55 billion of the total 84 billion cubic meters of water that flow down the river each year is allocated to Egypt. That lopsided arrangement is due in part to Egypt’s legacy as a British colony, when England was trying to maximize productivity in the delta.

A pair of accords, struck in 1929 and 1959, prioritized Egypt’s share of the water, including all dry season waters and veto power over any upriver projects.

But now those upriver African countries are asserting claims to water they consider their “fair share.”

“Egypt has every right to an equitable share of water, but the British colonial masters back in 1929 had a different idea of sharing—which we don’t recognize today,” said Teferra Shiawl, a former Ethiopian ambassador to the United Nations, and a senior adviser at the Centre for Dialogue, Research and Cooperation, an Addis Ababa-based think tank.

In 2010 six countries in the Nile basin—Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, and Burundi—signed the Entebbe Agreement, overturning previous-colonial-era treaties and allowing them to work on river projects without Cairo’s prior consent.

Egypt’s refusal to back the agreement was a failed attempt to assert regional hegemony over economically ascendant Ethiopia, Shiawl told Bloomberg Environment.

Furthermore, he said the dam is part of a larger strategy to develop a cross-border energy market serving all of Northeast Africa.

“The dam is being built on the border, and that water will simply flow out of Ethiopia and into Sudan, just as it has for millennia,” Shiawl said. “Not a single drop will be taken for irrigation.”

Coordination Among Rivals

Construction on the dam is set to be complete by early 2019. At this point the real debate, however, has shifted: How long will Ethiopia take to divert river water to fill up the massive 74 billion cubic meter reservoir behind the dam? And what effect will that have on downriver communities and countries?

Ethiopia “could decide to fill it up in as little as three years, or longer, but Ethiopia has invested in this dam and will want to start using it quickly,” Dunne said.

Dunne notes that even if Ethiopia takes five or six years to completely fill the reservoir, that would still translate into roughly 20 percent less water for Egypt during that time.

“The basic interpretation of international water politics is that no country will do anything to directly harm another country’s water supply,” said Matthew Bey, an analyst with the Austin, Texas, geopolitical intelligence firm Stratfor. “Well, Egypt is saying this dam will harm their water supply.”

Managing river flow along a system as vast as the Nile is difficult even when all the stakeholders are friendly with each other, Bey said.

“A lot of this is going to require close coordination between rivals,” he said. “Filling up the reservoir is one issue, but there are also releases from other dams, like the High Aswan Dam in Egypt.”

Bey said the international community appears to be backing Ethiopia.

“So, they’re going to have to suck it up and make a deal,” Bey said. “It would be better for Egypt to come to the table to negotiate, rather than just letting Ethiopia do whatever it wants.”

A Delicate Path Forward

Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry has reiterated his country’s commitment to a “declaration of principles” signed by Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan in 2015. Part of the document stipulates a process for adjudicating future water projects to avoid causing “significant damage” to other countries.

The declaration “will be, upon its full implementation, a successful model of cooperation in the Nile basin,” Shoukry said during a Jan. 17 televised press conference with his Ethiopian counterpart, Workneh Gebeyehu.

Some maintain there is enough water to go around, if the will is there.

“We need to think more in a cooperative and participatory way to increase the available resources we have, and not to fight each other on dividing them,” said Hani Sewilam, a professor of water resources and sustainable development at the American University in Cairo. “Egypt has a history of supporting Nile basin countries with upriver water projects. If we consider the basin as one unit, I am sure we will have enough water, energy and food for all.”

Sewilam points to a potential scenario that allows Ethiopia to fill up the reservoir at a reasonable pace, while buying Egypt more time to make changes to water usage practices.

The worst case, according to Dunne, is considerably less appealing.

“We could see Egypt increase its military ties with Eritrea, maybe start arming Ethiopian rebels, and eventually this proxy war boils over completely and we have conflict in the horn of Africa over water.”

For full references please use source link below.