Illegal wildlife trade likely unstoppable without dramatic shift in public awareness

Many American consumers may be unwittingly participating in a multibillion-dollar black market that is threatening animal species around the globe — including in the United States.

Officials admit they’re barely scratching the surface of this illicit and lucrative trade, which for smugglers carries the risk of hefty fines but relatively little prison time.

Criminal organizations that traffic in drugs and weapons have, according to federal authorities, boosted their earnings in recent years by adding to their inventories, everything from alligator boots and endangered fish bladders to live tigers and king cobras.

This illegal trade goes far beyond the well-publicized poaching of elephants for their ivory or rhinoceroses for their horns. Even pangolins, sought after for their scales and meat, and thought to be the world’s most heavily trafficked mammal, only make up only a tiny fraction of the variety of animals smuggled into the United States every year.

The overwhelming majority of illegal wildlife seized by federal officials from Southern California to New York to Miami is far less glamorous but increasingly imperiled, from sea cucumbers to iguanas to parrots to butterflies to coral.

One of the duties of the US Fish and Wildlife Service is to protect endangered species by enforcing treaties, rules and regulations with their counterparts around the world. The inspectors of the USFWS office in Torrance were busy on a recent Thursday at Los Angeles International Airport, in the passenger terminal checking travelers and in the freight terminals checking inbound and outbound items for compliance with those rules.

(John Gibbins)

(35 more photos can be accessed at source link below)

As habitat destruction and over consumption continues to threaten plants and animals around the world, this type of illegal harvesting can quickly take its toll, bringing creatures to the brink of extinction, said Brad Shaffer, director of UCLA’s Institute of the Environment and Sustainability.

“You can see this cycle where species go from being common to being rare because of the food trade, and then rare to extremely rare or extinct because of the exotic pet trade,” he said.

Illegally trafficked animals, he added, are “often not the charismatic megafauna that people think about, as opposed to the ball python trade of skins coming out of Africa or the just incredible movement of literally millions of turtles and tortoises across international boundaries illegally.”

A report in March from the National Wildlife Federation found that a third of America’s wildlife is at risk of being permanently wiped out. That research comes as scientists continue to debate whether the planet is on the verge of the largest mass extinction since the dinosaurs.

To help combat this staggering loss of biodiversity, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service says it pursues more than 10,000 wildlife crime investigations every year, resulting in roughly $20 million in fines and several dozen of years of prison time annually.

While these numbers might sound impressive, a closer look reveals an agency overwhelmed by the sheer volume of animals and products flooding into the country.

I have to say, it’s overwhelming how much is out there and how few of us there are. — Erin Dean, resident agent in charge of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Southern California

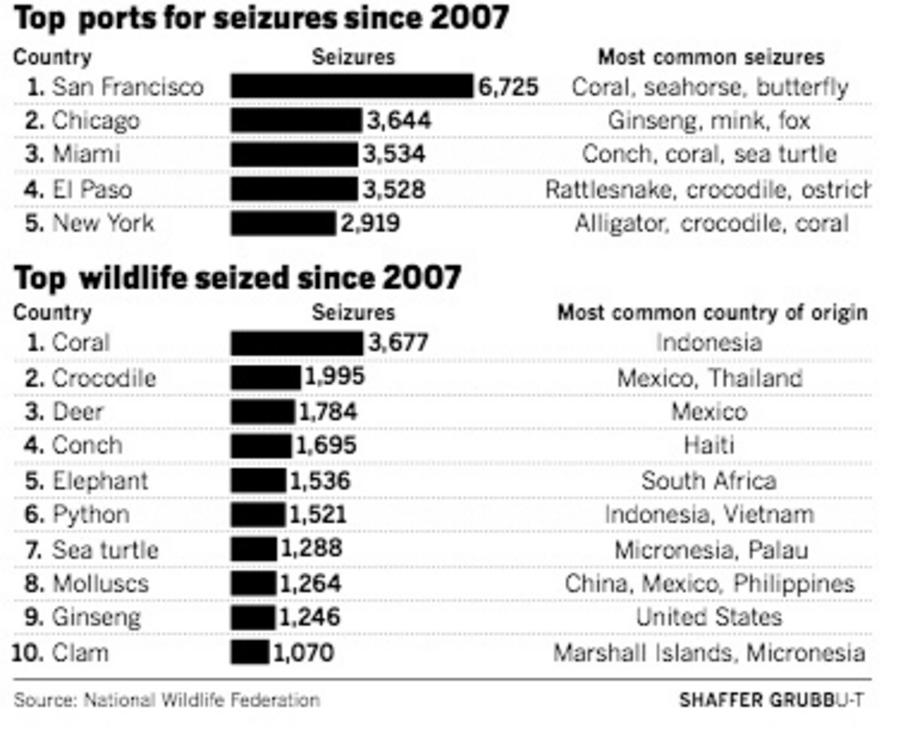

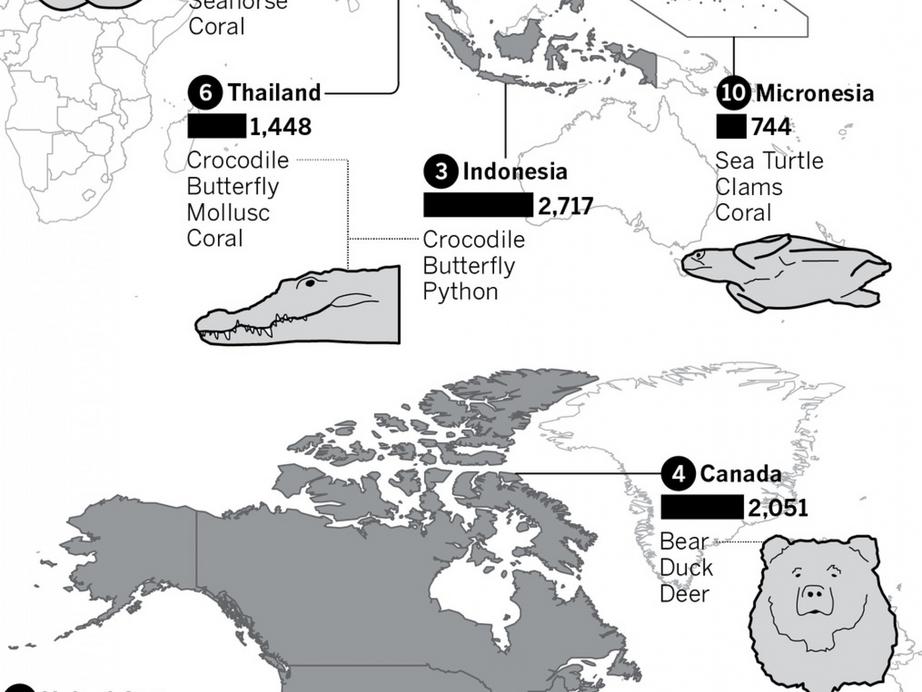

Data obtained by the San Diego Union-Tribune from the wildlife service show that since 2004 inspectors have conducted an average of fewer than 4,300 seizures a year at ports around the country. Live animals account for only about 230 of those seizures annually, more than half of which are for coral.

That’s just 11 seizures a day at docks, airports and land borders in roughly 70 metropolitan regions around the country. Half of those cases are people caught bringing in items for personal use, such as an ivory statue ordered through the mail or snake-skin boots purchased while on vacation.

Wildlife service officials have been candid about the agency’s lack of capacity, given its limited workforce. The federal Fish and Wildlife service employs about 355 inspectors and agents for the entire U.S, staffing levels that have been effectively unchanged for decades.

- “I have to say, it’s overwhelming how much is out there and how few of us there are,” said Erin Dean, resident agent in charge of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Office of Law Enforcement in Southern California.

“I get asked a lot how much do you miss,” added the 24-year veteran, who oversees 17 inspectors and agents in Los Angeles County and four in San Diego. “Well, I don’t know. But with so few of us, I can’t imagine what gets across without us knowing, unfortunately.”

In addition to traditional inspection efforts at sea and airports, Dean said recently her team has put more of a focus on undercover investigations that target criminal enterprises in the community.

Last fall they announced the biggest wildlife trafficking bust in Southern California history. Operation Jungle Book charged 16 people and seized 200 animals, including monitor lizards, king cobras and a Bengal tiger.

“We are getting smarter,” Dean said. “We are working in areas that we haven’t worked in the past. Our intel unit has blossomed.”

Still, it’s unclear if this approach can make a significant difference as long as demand remains strong for exotic pets and animal products.

As law enforcement struggles to keep up with the flood of wildlife brought into the country, complex rules for shipping wildlife make it often impossible for the average consumer to discern what’s been illegally trafficked. Even frontline officers with U.S. Customs and Border Protection, which wildlife inspectors rely heavily upon to flag them to potential abuses, can be unfamiliar with the maze of laws that govern the importation of certain species.

Complicating the issue, illegal wildlife often makes its way across international borders as part of otherwise legitimate commercial shipments, which are regulated under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora or CITES.

On Thursday at a warehouse in Los Angeles International Airport, Dean and her team cut open several boxes of live coral from Indonesia during a routine inspection. Nobody seemed too surprised to find that the specimens — most likely destined for personal aquariums — had been rubber-banded together to avoid international quotas allowed under the shipment’s CITES permit.

While the undeclared coral was confiscated, the rest of the shipment was allowed through. It was clear that for businesses, bending the rules came with little consequences.

That’s why some animal advocacy organizations have urged people to forgo buying all exotic pets and nonessential wildlife products.

“Our main message is that when the buying stops, the killing does too,” said John Baker, chief program officer of WildAid. “You can live without wildlife products. Don’t buy them.”

WildAid has worked with shipping companies to ban delivery of technically legal animal products that often get mingled with illegal shipments, such as the United Parcel Service of America, UPS, did several years ago for shark fins.

Baker said other companies, such as FedEx, have balked at drawing such a hard line.

In response to questions about its policy around shipping wildlife, FedEx said in an email that it’s committed to strict compliance with the law: “We have long been opposed to the trafficking of animal parts that are obtained from the exploitation of any species protected by law.”

Because so much of illegal wildlife is purchased and traded on line, a number of tech companies announced in March a campaign to reduce trafficking on their platforms by 80 percent within the next two years by blacklisting companies known to engage in such activities. Etsy, eBay, Facebook and Google are a few of the 21 businesses that have joined the effort, which was spearheaded by The World Wildlife Federation and other advocacy groups.

These efforts come as illegal smugglers have started to increasingly targeting wildlife in North America to replace stocks of wildlife that have been decimated in other parts of the globe. Increasingly, succulents from California, turtles from the Gulf Coast, eels from Maine and fish from Baja California have been targeted by those looking to capitalize on the exploitation of such animals.

In Southern California, wildlife service officials said their highest priority is catching smugglers of the totoaba fish, which are poached in the Sea of Cortez located in the Gulf of California and then shipped overseas from international ports in Ensenada and Southern California.

The fishing village of San Felipe has embraced using gill nets to illegally capture the massive 120-pound fish and cut out their bladders, which when dried sell for as much as $30,000 in China. In the process, the nets suffocate other wildlife species, from whales to sharks to sea turtle to dolphins and rays.

Fishing the totoaba, which is itself listed as critically endangered, has also brought the vaquita porpoise to the brink of extinction. Experts believe there are fewer than 30 left in the world.

Andrea Crosta, executive director of Elephant Action League, has been tracking the totoaba trade from remote parts of China to Baja. He estimates that hundreds of bladders are being trafficked out of the Sea of Cortez every month by Mexican cartels and other criminal middlemen.

“There’s no law enforcement,” he said. “It’s a lucrative trade and pretty much risk free. It’s gold swimming in the water.

“The fisherman are very poor,” he added. “The make maybe $500 a month and just one totoaba is $5,000.

There have been a handful of busts for totoaba by agents in San Diego and Los Angeles counties, but nothing compared with the volume that’s making its way to foreign markets, Crosta said.

“Certainly it goes through the border,” he said. “They don’t really check much. I did it myself walking in and out many times.”

This situation has led Crosta to the same conclusion as WildAid and other animal advocacy groups that government enforcement alone will not end trafficking of endangered animals.

Federal officials have also recognized the need for increased public awareness. Thanks to public-private partnerships, billboards and signage about the impacts of wildlife trafficking are staples in airports around the country. Wildlife service officials also regularly conduct public outreach events in schools and other venues.

Dean, with Fish and Wildlife in Southern California, said it can be overwhelming for consumers to discern what’s legal, so she always tells people the same thing: “If you don’t know, don’t buy it.”

For the rest of this article please go to source link below.