Illegal loggers ‘cook the books’ to harvest Amazon’s most valuable tree

- A new study finds that illegal logging, coupled with weak state-run timber licensing systems, has led to massive timber harvesting fraud in Brazil, resulting in huge illicit harvests of Ipê trees. This process is doing major damage to the Amazon, as loggers build roads deep into forests, causing fragmentation and creating greater access.

- To reduce document fraud, the Brazilian federal government this month required that all states register or integrate their timber licensing systems within a national timber inventory and tracking system known as Sinaflor. While this should reduce fraudulent paperwork, onsite illicit timber harvesting practices remain a major problem.

- Better oversight of forest management plans and more onsite inspections of timber operations are needed to curb illegal logging practices and to prevent harvesting on public lands and in indigenous reserves. The high value of Ipê wood — selling for up to $2,500 per cubic meter at export — makes it very profitable for illegal loggers.

- Ipê wood is largely shipped to the U.S. and Europe. Analysts say that buyers all along the timber supply chain turn a blind eye toward fraud, with sawmills, exporters, and importers trusting the paperwork they receive, rather than questioning whether the lower prices they pay for Ipê and other timber may be due to timber laundering.

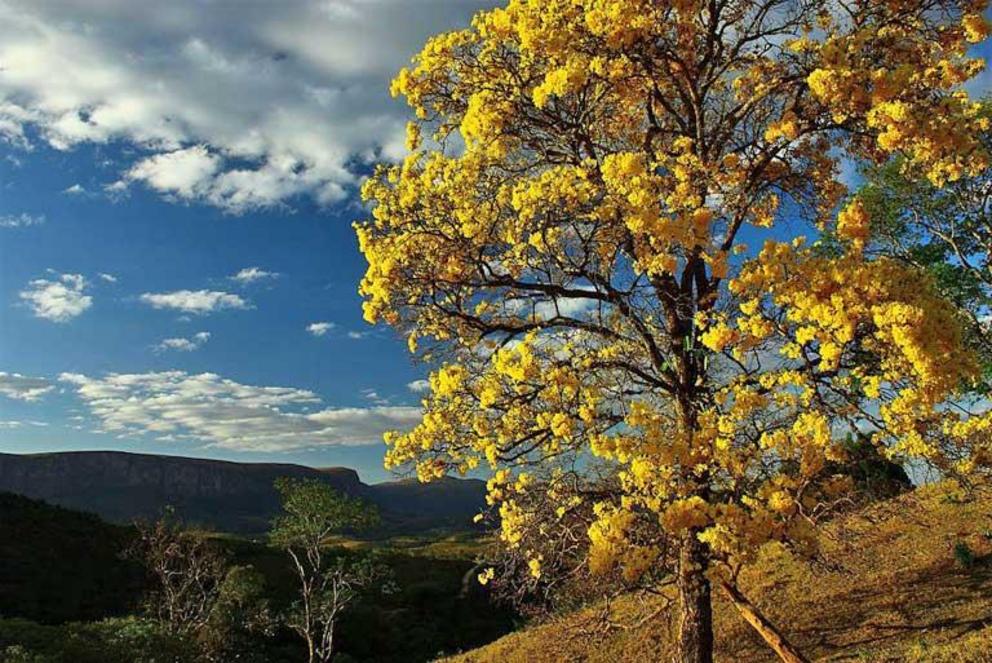

Brazil’s Ipê tree is one of the most valuable tree species in the world, and a chief target for illicit deforestation, with primary export markets for its illegally harvested timber especially found in the U.S. and Europe.

In the past, a weak licensing system, along with continued indiscriminate, illicit logging of Ipê (formerly Tabebuia spp., but reclassified as Handroanthus spp.), has caused serious damage to the Amazon rainforest according to a Greenpeace Brazil investigation.

The high value of Ipê wood — which made into flooring or decking can sell for up to US $2,500 per cubic meter at Brazilian export terminals — makes it very profitable for loggers, even though they must penetrate deep into forests to harvest the trees.

The resulting environmental harm is severely impacting the Brazilian Amazon, says the report, with deep encroachment by illegal roads, increased forest degradation and fragmentation, harm to biodiversity, and intensification of violence in rural areas.

A Logging Authorization (AUTEF) site with an approved Forest Management Plan (PMFS) in Rurópolis, Pará state. In October 2017, Greenpeace accompanied teams from the Brazilian Institute for the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) on PMFS inspections. The goal was to identify fraud in forest inventories. Nonconformities were found in every PMFS site visited. Image © Marizilda Cruppe / Greenpeace

Fraud at the heart of the problem

The report, Imaginary Trees, Real Destruction reveals that “the illegal logging of Ipê trees is facilitated by weaknesses in the state-level licensing process for forest management plans,” a problem that the federal government is seeking to solve with a national inventory and tracking system.

A Greenpeace field investigation conducted in Southwest Pará state found that corrupt forest engineers fake forest inventories by deliberately misidentifying undesirable trees as commercially valuable species, overestimating the volume of valuable trees, or listing non-existent specimens. State agencies, relying on these fraudulent inventories, then issue credits that allow the harvesting and shipping of non-existent timber. These wildly inflated forest credits are then used to “cook the books” at sawmills that illegally process Ipê trees cut within protected Brazilian conservation units or on indigenous reserves.

The high rate of fraud and the commonplace laundering of illegally harvested Ipê trees is made easier due to an absence of government conducted field surveys in areas with approved Sustainable Forest Management Plans (PMFS), and also, until this month, by the lack of an integrated national licensing system for timber in Brazil.

While some perpetrators are caught, many more escape detection.

As a result,” At present, it is safe to say that it is almost impossible to guarantee if timber from the Brazilian Amazon originated from legal operations, let alone from operations that do not violate human rights or environmental laws,” says Greenpeace Brazil’s Amazon campaigner, Rômulo Batista.

“Brazil urgently needs a forest governance and an enforcement system capable of ensuring that all timber logged in the Brazilian Amazon is extracted legally and with full regard to the rights of its Indigenous peoples and other traditional inhabitants,” he says.

The tree cut at this location was listed in the forest inventory as Ipê, but the correct species is Jarana — evidence of fraud and an attempt to launder illegal timber. Image © Marizilda Cruppe / Greenpeace

Brazil moves toward a national timber tracking system

“In order to change this scenario, Brazil needs a forestry governance, which begins with Sinaflor [the National System for the Control of the Origin of Forest Products]. This [comprehensive inventory and tracking] system… needs to be transparent and accessible to the public to be truly effective,” Batista told Mongabay.

All Brazilian states had until 2 May of this year to register their forest control systems with Sinaflor, the timber inventory tracking system launched in March 2017 by IBAMA, Brazil’s federal environmental protection agency. Sinaflor is a national level digital system that allows for data cross-checking of all state and federal inventory systems. Its implementation should help overcome deficiencies in the state systems and better facilitate fraud detection at multiple points along the supply chain.

According to IBAMA, 21 states were ready to utilize the new digital platform by March of this year, including Amazonas, Roraima and Tocantins. The remaining states not ready to utilize the system at that time included Bahia, Espírito Santo, São Paulo, Santa Catarina, and importantly Pará and Mato Grosso. The latter two are the largest producers of timber in Legal Amazonia.

IBAMA has confirmed to Mongabay that all states have now registered or integrated their state systems with Sinaflor, meeting the 2 May deadline. Mato Grosso, Mato Grosso do Sul, Pará, Santa Catarina and São Paulo already had their own computerized forest control systems, which have been integrated into Sinaflor.

From 2 May on, all new forestry projects in Brazil will have to be registered in the national system. Existing logging plans filed prior to that date will need to be registered by 31 December. It is hoped, say officials, that the interfacing of state and national systems will lead to less fraud and lower rates of illegal Ipê harvesting.

IBAMA officers measure the volume of timber and confirm botanical identification at a sawmill suspected of receiving illegal Ipê logs in Uruará, Pará state. Experts say that fraud is occurring along the entire timber supply chain. Image © Marizilda Cruppe / Greenpeace

Searching out fraud

In their study, Greenpeace and University of São Paulo (USP) researchers analyzed 586 Logging Authorizations (AUTEF) issued by the Environment and Sustainability Secretariat of Pará (SEMAS) between 2013 and 2017. The agency lists Ipê (Handroanthus spp.) as a harvestable species, with quotas set based on ipê tree volumes on site. When a Sustainable Forest Management Plan (PMFS) is approved, the AUTEF documents must show the total number of ipê trees and volumes of logs that will be removed from the licensed site. Those numbers will subsequently generate commercial credits.

The researchers compared reported forest densities of Ipê trees with those found in published scientific literature and in the inventories of five national forests in Pará. This careful analysis found that more than 77 percent of the AUTEFs had reported Ipê tree volumes up to ten times higher than the natural levels at which that species occurs, making fraud likely in more than 450 cases.

Greenpeace, working with USP Luiz de Queiroz College of Agriculture researchers and IBAMA technicians, also conducted field surveys in six Forest Management Areas (AMF) in Pará, between October and November of last year. They found that all of these AMFs showed evidence of incorrect botanical identification, overestimation of the volume of timber declared in forest inventories, and/or a record of non-existent trees. All of these practices are commonly employed for the laundering of illegal timber.

IBAMA inspectors at a Logging Authorization (AUTEF) site with an approved Forest Management Plan in Uruará, Pará state. Greenpeace and University of São Paulo researchers analyzed 586 AUTEFs and found that more than 77 percent reported Ipê tree volumes up to ten times higher than the natural levels at which that species occurs, making fraud likely in more than 450 cases. Image © Marizilda Cruppe / Greenpeace

The Mato Grosso example

According to IBAMA, the Environment Secretariat of Mato Grosso (SEMA) has completed transfer of its Sisflora system to Sinaflor, which is good news for guarding against fraud. But funding shortfalls could still seriously hinder accurate timber tracking in the state. “We are improving in environmental management, investing in technicians, equipment, and in bidding for the purchase of high-resolution satellite images. In terms of action, however, the [budget] is almost drained,” André Baby, secretary of SEMA in Mato Grosso, told Mongabay. “There is a shortage of public resources.”

Of all Brazilian states, Mato Grosso has among the highest rates of deforestation due to rapidly expanding soy and beef production, with the state responsible for 20 percent of all the deforestation detected in Legal Amazonia between August 2016 and July 2017, based on data from the National Institute for Space Research (INPE), and an analysis by the Instituto Centro de Vida (ICV), an NGO.

Of great concern to environmentalists is the amount of deforestation that isn’t authorized or tracked: 90 percent of the more than 130,000 hectares (501 square miles) of forest destroyed during the 2016/2017 period in Mato Grosso was not authorized by SEMA. That result is, however, slightly better compared to 2015/2016, when the illegal unauthorized harvest accounted for 95 percent of trees cut.

SEMA’s secretary, when questioned by Mongabay, chose to point out more positive Mato Grosso forestry data. While the state saw a 49 percent increase in illegal deforestation in 2014/2015, he noted, that rate fell to 16 percent in 2015/2016, and to a 10 percent increase for 2016/2017.

Still, such large illegal harvests don’t bode well for the state’s future international climate commitments. Mato Grosso declared a goal of zero illegal deforestation by 2020 at the COP 21 Paris climate change summit in 2015. And during COP 23 in 2017, Mato Grosso announced the receipt of R$ 178 million (US $56 million) from Germany and the United Kingdom to expand its programs to reduce deforestation. But, as in neighboring Pará, that investment will have little value without the elimination of fraud in the field, accurate timber inventories and tracking, and much better state and federal enforcement against large-scale illegal logging operations.

An ipê (Handroanthus albus) in Jalapão, Tocantins — one of the most valuable tree species in the Amazon and also a primary target of illegal loggers. Image by Hermínio Lacerda / Banco de Imagens do IBAMA.

“Companies are aware”

Although the Sinaflor national tracking system could be a major step forward in limiting timber harvesting fraud, that system will likely achieve only limited success because the government lacks the capacity to conduct onsite inspections in Forest Management Areas, according to Jeanicolau de Lacerda from the Brazilian Coalition on Climate, Forests and Agriculture.

“This gap opens the door to illegality. Monitoring [onsite] is a difficult job to tackle, and forests will only have security with frequent field surveillance,” he told Mongabay.

But Brazil’s federal and state governments aren’t the only parties able to curb illegal deforestation, says Greenpeace. Their study found that buyers all along the timber supply chain turn a blind eye toward fraud.

Of the 142 PMFSs analyzed, 115 moved Ipê credits into the state Sisflora system. Of these, 79 PMFSs generated credits with suspicion of illegality, with the probably illicit timber then exported by 53 companies, and brought to 30 nations by 116 importing companies, between March 2016 and September 2017.

According to Greenpeace, 37 companies from the United States imported 10,171 cubic meters of Ipê over that period, making the U.S. the largest destination for this type of wood. Among the biggest buyers: Pennsylvania’s Thompson Mahogany Company (1,797 cubic meters); Florida’s International Lumber Imports IC (1,318 cubic meters); and Georgia’s UFP International LLC (834 cubic meters).

The U.S., together with Europe, accounts for 97 percent of exported Brazilian Ipê. Over the 2016/2017 period, eleven European nations purchased 9,775 cubic meters, including France (3,002 cubic meters), Portugal (1,862 cubic meters), Belgium (1,754 cubic metes) and the Netherlands (1,549 cubic meters). Japan, Canada, Israel, China, Argentina and India account for much of the rest.

Importantly, these countries and companies generally accept the legality of Ipê shipments, and the paperwork accompanying them, on face value. “Reluctant to adopt risk mitigation measures to avoid contamination of their chains of custody, companies rely on official documents that do not guarantee the origin and legality of the timber they receive,” Greenpeace reports.

Lacerda, a forestry consultant for Precious Woods, a certified timber company in Switzerland, says that many import-export companies know when they are buying illegal timber, and they also know that purchasing it saves them money: “That [illicit] production does not pay taxes, does not bear the costs of a proper forest management [plan], so it is 30 percent to 40 percent cheaper. Our company, for instance, cannot compete with the illegal timber sold in the Brazilian market.”

“The problem is that certified wood is little known, even among final consumers in rich countries,” concludes Lacerda. “As long as the [public] doesn’t know what they are buying, and do not take a stand, the situation will remain exactly the same.”

For full references please use source link below.