Genetic study shakes up the elephant family tree

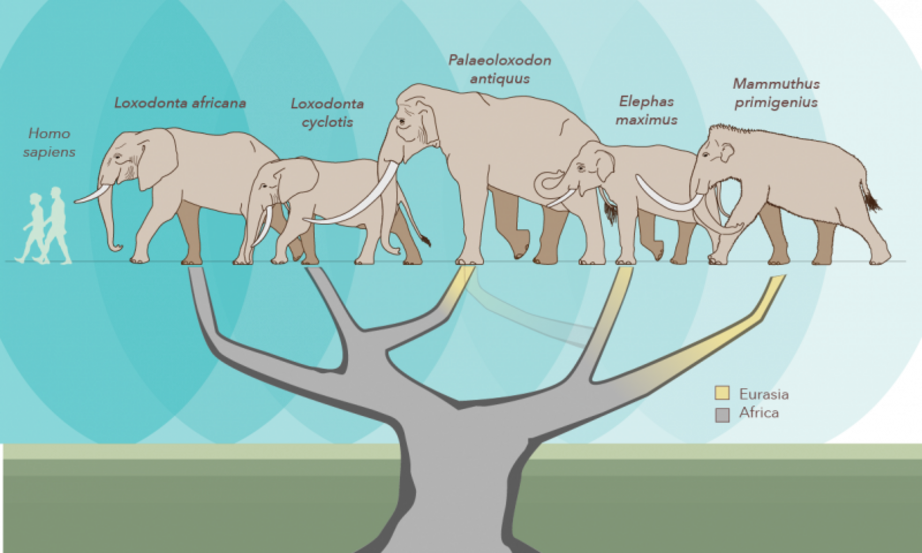

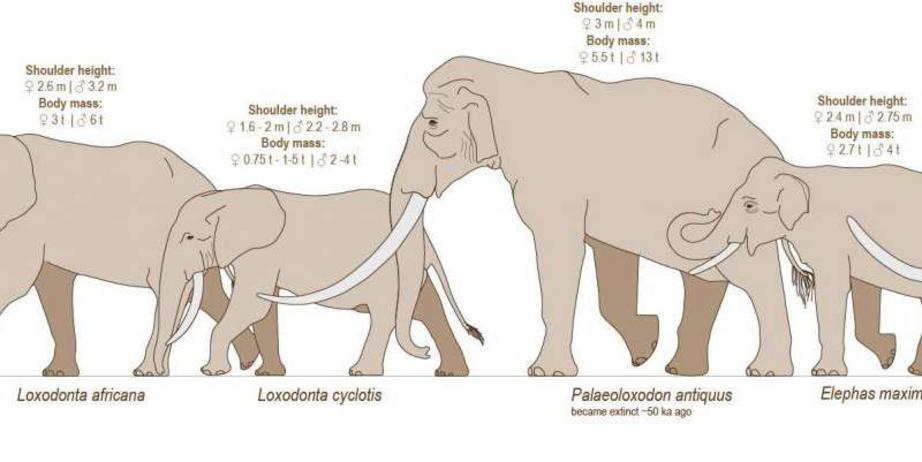

New research reveals that a species of giant elephant that lived 1.5 million to 100,000 years ago - ranging across Eurasia before it went extinct - is more closely related to today's African forest elephant than the forest elephant is to its nearest living relative, the African savanna elephant.

The study challenges a long-held assumption among paleontologists that the extinct giant, Palaeoloxodon antiquus, was most closely related to the Asian elephant. The findings, reported in the journal eLife, also add to the evidence that today's African elephants belong to two distinct species, not one, as was once assumed.

A new study reconfigures the elephant family tree, placing the giant extinct elephant Palaeoloxodon antiquus closer to the African forest elephant, Loxodonta cyclotis, than to the Asian elephant, Elephas maximus, which was once thought to be its closest l

A new study reconfigures the elephant family tree, placing the giant extinct elephant Palaeoloxodon antiquus closer to the African forest elephant, Loxodonta cyclotis, than to the Asian elephant, Elephas maximus, which was once thought to be its closest l

Understanding their genetic heritage is key to keeping today's elephants from going extinct, said University of Illinois animal sciences professor Alfred Roca, a co-author of the new study. Roca led research in the early 2000s that provided the first genetic evidence that African elephants belonged to two distinct species. Subsequent studies have confirmed this, as does the new research.

"We've had really good genetic evidence since the year 2001 that forest and savanna elephants in Africa are two different species, but it's been very difficult to convince conservation agencies that that's the case," Roca said. "With the new genetic evidence from Palaeoloxodon, it becomes almost impossible to argue that the elephants now living in Africa belong to a single species."

For the new analysis, scientists looked at two lines of evidence from African and Asian elephants, woolly mammoths and P. antiquus. They analyzed mitochondrial DNA, which is passed only from mothers to their offspring, and nuclear DNA, which is a blend of paternal and maternal genes.

The researchers relied on the most sensitive laboratory techniques to extract and amplify the DNA in P. antiquus bones from two sites in Germany - among the first DNA successfully collected from such ancient bones from a temperate climate.

"Up until now, genetic research on bones that are hundreds of thousands of years old has almost exclusively relied on fossils collected in permafrost," said Matthias Meyerl, a researcher from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and first author of the paper. "It is encouraging to see that recent advances in laboratory methods are now enabling us to recover very old DNA sequences also from warmer places, where DNA degrades at a much faster rate."

A new genetic analysis clarifies the evolutionary relationships between five elephant species.

A new genetic analysis clarifies the evolutionary relationships between five elephant species.

The mitochondrial analysis revealed that a shared ancestor of P. antiquus and the African forest elephant lived sometime between 1.5 million and 3.5 million years ago. Their closest shared ancestor with the African savanna elephant lived between 3.9 and 7 million years ago.

The nuclear DNA told the same story, the researchers report.

"From the study of bone morphology, people thought Palaeoloxodon was closer to the Asian elephant. But from the molecular data, we found they are much closer to the African forest elephant," said research scientist Yasuko Ishida, who led the mitochondrial sequencing of modern elephants with Roca.

"Palaeoloxodon antiquus is a sister to the African forest elephant; it is not a sister to the Asian elephant or the African savanna elephant," Roca said.

"Paleogenomics has already revolutionized our view of human evolution, and now the same is happening for other mammalian groups," said study co-author Michael Hofreiter from the University of Potsdam, an expert on evolutionary genomics. "I am sure elephants are only the first step and in the future, we will see surprises with regard to the evolution of other species as well."Michael

Understanding the genetic heritage of elephants is vital to protecting the living remnant populations in Africa and beyond, Roca said.

"More than two-thirds of the remaining forest elephants in Africa have been killed over the last 15 years or so," Roca said. "Forest elephants are among the most endangered elephant populations on the planet. Some conservation agencies don't recognize African forest elephants as a distinct species, and these animals' conservation needs have been neglected."

Journal reference: eLife

Provided by: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign