Entire populations of Antarctic birds failed to breed last year because of extreme snowstorms

South polar skua (Stercorarius maccormicki).

Climate-change-related storms made it impossible for hundreds of thousands of polar seabirds to breed last year.

Anyone who has seen the documentary "March of the Penguins" (also known as the best movie ever) knows how rough polar life can be. Polar seabirds are adapted to withstand the Antarctic's uniquely harsh conditions—but it's not easy. They somehow manage to exist in the land mass that takes the prize for being the coldest, driest, highest, and windiest continent on Earth.

But even so, the extremes delivered by climate change are proving too much for them to bear. A new study reveals that from December 2021 to January 2022—during prime time for Antarctic birds to breed—researchers did not find any nests in areas where colonies are generally comprised of hundreds of thousands of birds.

“We’re talking about tens if not hundreds of thousands of birds, and none of them reproduced throughout these storms. Having zero breeding success is really unexpected.”

It's no secret that climate change boosts both the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, most of which negatively impact wildlife in one way or another. In polar environments, "such events include heat waves, anomalous sea ice concentrations and storms," write the authors of the study. "Although extreme weather events affect [polar seabirds'] breeding success and other demographic rates, they are thought to affect only a part of the population. Complete breeding failure of an entire population due to extreme environmental conditions is rarely observed," they add.

An Antarctic petrel glides over ocean in Antarctica.

An Antarctic petrel glides over ocean in Antarctica.

The study describes how extreme, climate-change-related snowstorms in Dronning Maud Land, Antarctica, in late 2021/early 2022 caused "almost complete and large-scale breeding failures" of the area’s three most common seabird species: Antarctic petrel (Thalassoica antarctica), Snow petrel (Pagodroma nivea) and South polar skua (Stercorarius maccormicki).

“We know that in a seabird colony, when there’s a storm, you will lose some chicks and eggs, and breeding success will be lower,” says Sebastien Descamps, first author of the study and researcher at the Norwegian Polar Institute. “But here we’re talking about tens if not hundreds of thousands of birds, and none of them reproduced throughout these storms. Having zero breeding success is really unexpected.”

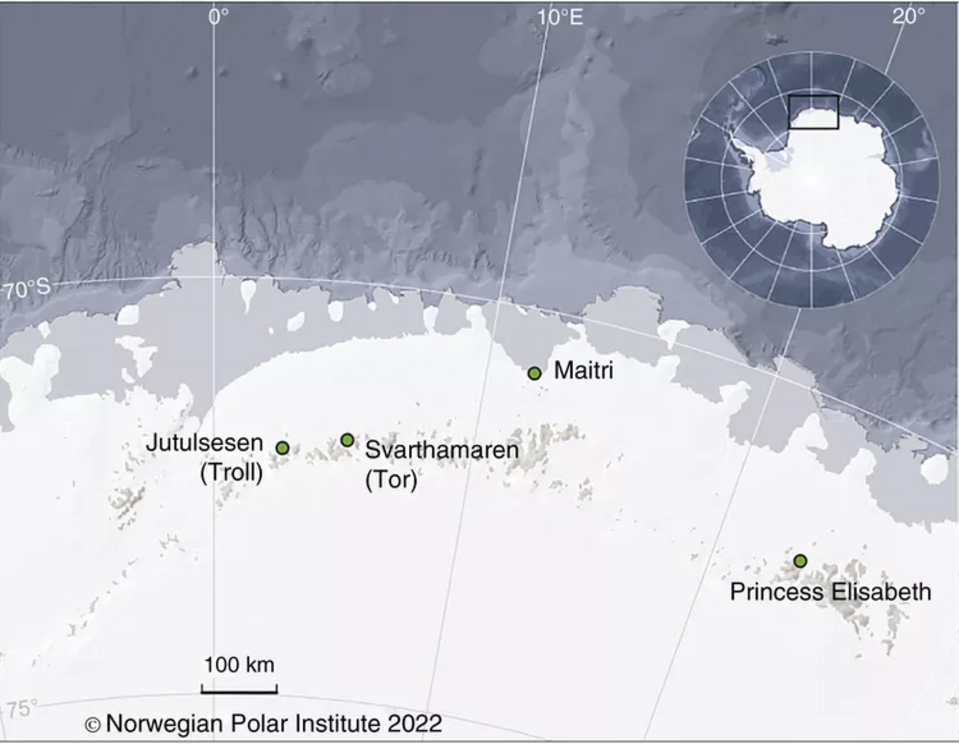

Locations of the breeding sites mentioned in the study.

Locations of the breeding sites mentioned in the study.

The research focuses on Antarctica's Dronning Maud Land, which includes Svarthamaren and nearby Jutulsessen. These areas are renowned for hosting two of the world’s largest Antarctic petrel colonies. They are also essential nesting grounds for snow petrels and south polar skua.

From 1985 to 2020 in Svarthamaren, the colony contained between 20,000 and 200,000 Antarctic petrel nests, around 2,000 snow petrel nests, and over 100 skua nests annually, according to the study.

Shockingly, in Svarthamaren during the 2021–2022 season, there were only three breeding Antarctic petrel, a handful of breeding snow petrels, and zero skua nests. Mind you, Svarthamaren has long been described as the world’s largest colony of antarctic petrels. In Jutulsessen, there were no Antarctic petrel nests in summer of 2021 to 2022 (that's southern hemisphere summer, so December and January), despite tens of thousands of active nests in previous years.

“It wasn’t only a single isolated colony that was impacted by this extreme weather. We’re talking about colonies spread over hundreds of kilometers,” says Descamps. “So these stormy conditions impacted a really large part of land, meaning that the breeding success of a large part of the Antarctic petrel population was impacted.”

A south polar skua chick resting in the snow Ross Island, Antarctica, in a previous season.

A south polar skua chick resting in the snow Ross Island, Antarctica, in a previous season.

For birds like these that lay their eggs on bare ground, too much snow renders the ground inaccessible and makes it impossible to raise chicks. The storms also mean that the birds need to spend their precious strength in sheltering, keeping warm, and conserving energy.

While the potential warming of the region has been a concern, researchers are now realizing that's just the tip of the iceberg, so to speak.

“Until recently, there were no obvious signs of climate warming in Antarctica except for on the peninsula,” says Descamps. “But in the last few years, there have been new studies and new extreme weather events that started to turn the way we see climate change in Antarctica.”

The study, “Antarctic climate change: Extreme snowstorms lead to large-scale seabird breeding failures in Dronning Maud Land," was published in Current Biology.