China’s first national park

A far-flung locale in Qinghai province will become China’s first official national park. There, Tibetan nomads are long accustomed to living with their snow leopard neighbors. However, tensions between people and the endangered cats persist.

- Sanjiangyuan National Park is expected to open in 2020 as China’s first park in its new national park system.

- As many as 1,500 endangered snow leopards (Panthera uncia) live in the area. The cats are subject to poaching and persecution in retaliation for their predation on livestock, which are edging out their natural prey.

- The new park seeks to capitalize on the reverence many local Tibetan Buddhists have for wildlife, employing a conservation model that engages the public and attempts to ease tensions between people and predators.

- The new national park system is intended to create a more effective kind of protected area than currently exists in China.

Late at night on March 15, a snow leopard secretly entered the sheepfold of a Tibetan household in a remote pastureland in China’s western Qinghai province, killing one sheep. Local Tibetan nomads captured the cat and sent it back up into the surrounding mountains.

Within two days, it returned to the same settlement twice and killed more sheep. After consulting with a wildlife expert, the local people realized that the animal was an aging cat that probably couldn’t survive without resorting to easy livestock kills and finally sent it to the Quinghai Wildlife Rescue and Breeding Center in Xining, the province’s capital city.

It is fairly common for people living in most parts of Qinghai Province’s Sanjiangyuan region to spot snow leopards (Panthera uncia), a generally elusive creature locals have nicknamed “snow mountain hermit.” It is also common for them to lose livestock to the cats, as well as to other carnivores that thrive in Sanjiangyuan’s rugged alpine terrain.

Now the Chinese government is working to establish its first national park in the area, Sanjiangyuan National Park. The goal is to protect Sanjiangyuan’s tremendous water resources and rich biodiversity, including the area’s flagship species, the snow leopard. The big cats are subject to persecution in retaliation for livestock kills as well as to poaching. Figuring out how to help humans and snow leopards co-exist will be essential to the new park’s success at protecting the endangered cats.

A snow leopard in China’s Sanjiangyuan region. Photo courtesy of Shanshui Conservation Center.

Source of three rivers

Baima Angzhou, a 61-year-old Tibetan nomad, lives in one of the Sanjiangyuan region’s alpine pastures at about 4,000 meters. Inside his family tent last August, Baima told Mongabay that a diverse range of wildlife frequently wanders near his home.

According to Baima, brown bears have visited the family tent a few times when no one was home, destroying the tent and eating some food.

“In my memory, wildlife has increased in number in recent decades and it has also become common for us to spot snow leopards,” Baima said. He attributes the change to a reduction in poaching.

People here are used to cohabiting with wildlife. On the area’s high elevated pastureland and mountain regions, locals make frequent sightings of blue sheep (Pseudois nayaur), white-lipped deer (Cervus albirostris), alpine musk deer (Moschus chrysogaster), Rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta), wild boars, (Sus scrofa), Chinese mountain cats (Felis bieti), red foxes (Vulpes vulpes), and other creatures.

Indeed, in an area near where Baima lives, another Tibetan nomad named Luo Zhu told this reporter that most families lose between three and five cattle annually to snow leopards or wolves.

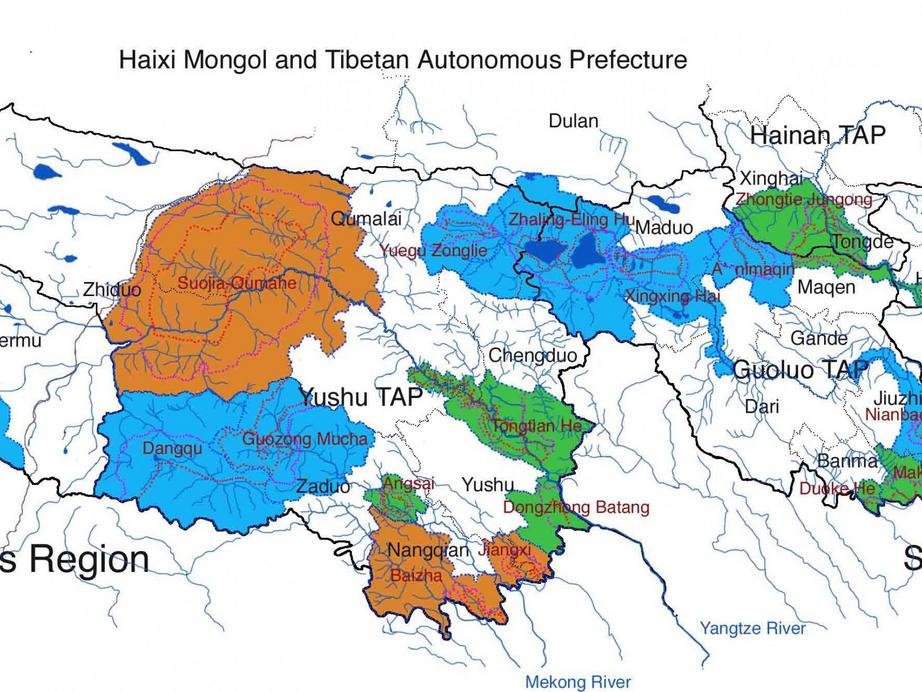

Over the past three years, China has been pushing toward establishing a national park system in order to create a more effective kind of protected area than currently exists in the country. As the first of the system’s nine pilot projects, in 2015 the government began work to establish a huge 123,000 square kilometer (nearly 47,500 square mile) national park in the Sanjiangyuan region — an area roughly the size of North Korea. Sanjiangyuan National Park, which will overlap part of the existing Sanjiangyuan National Natural Reserve, is expected to be complete by 2020.

Sanjiangyuan means “source of three rivers,” referring to the area’s status as the headwaters of the powerful Yellow, Yangtze, and Mekong rivers. Fifteen percent of the Mekong’s water discharge, 25 percent of the Yangtze’s, and 49 percent of the Yellow’s originate here.

In addition to its unique topography and rich water resources, the region is also famous for its well-preserved flora and fauna. The national park is home to 760 vascular plant species, 59 bird species, 15 fish species, and 125 wild mammal species. Most of these are unique to the broader Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Eight mammal species that live in the region are listed as China’s first class national protected animals, a designation that confers the highest level of protection: snow leopard, Tibetan antelope (Pantholops hodgsonii), wild yak (Bos mutus), Tibetan wild ass (Equus kiang), white-lipped deer, alpine musk deer, argali (Ovis ammon), and leopard (Panthera pardus).

Thanks to its remoteness and sparse population, as well as the Buddhism-dominated local culture, Sanjiangyuan National Park and the surrounding region have been able to maintain a fairly intact ecosystem. That is why the endangered snow leopard remains a frequent visitor to human settlements in the area.

In 2016, infrared cameras on the upper stream region of the Mekong (called the Lancang in China) within the national park captured the world’s first footage of wild snow leopards mating. The videos showed that there is a healthy breeding population in the region, Lü Zhi, a conservation biologist at Peking University and founder of the wildlife conservation NGO Shanshui Conservation Center (SCC), told Chinese media in April 2016. According to SCC estimates, roughly 1,000 to 1,500 snow leopards live in the Sanjiangyuan region.

Rugged mountains in the Sangjiangyuan region, a favorite habitat of the snow leopard. Photo by Wang Yan for Mongabay.

A new model for China

For the majority of Tibetans, spotting a snow leopard is a blessing. The animal is even regarded as a sacred creature by Buddhists. To capitalize on this reverence for snow leopards and wildlife in general, Sanjiangyuan National Park is expected to employ a conservation model that enlists public participation in conservation activities and scientific research.

“Appointed rangers are responsible for tending the pastureland, wetland area, anti-poaching, camera trap installation, environmental monitoring, and litter removal within the national park area,” Sanjiangyuan National Park official Tsedan Druk told this reporter for a story published in NewsChina last December.

“This will directly benefit locals by increasing their family income by a significant amount for a local household with average income in the region,” Tsedan said. Part of the idea is to eliminate the need for poorer households to resort to poaching to make a living.

China boasts about 10,000 protected areas and compared with other nations has a high proportion of its land territory — up to 18 percent — categorized as protected. But it lacks a unified system to regulate and safeguard these regions. Fragmented management and insufficient funding are threatening most protected areas’ conservation efforts.

Sanjiangyuan National Park is intended to be different. According to its latest draft management plan, presented in March 2017, the park has formed a new kind of integrated management system, with personnel separated from all other government departments. This represents a stark contrast with China’s existing system of protected areas. In Tsedan’s opinion, this will enable more effective management and ecological protection of the park and its vicinity.

Remaining threat

The snow leopard, listed as Endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, inhabits the alpine zone of Central Asia, with its main habitat in the Altai, Tian Shan, Kun Lun, Pamir, Hindu Kush, Karakorum, and Himalayan ranges. There are about 2 million square kilometers (770,000 square miles) of suitable snow leopard habitat.

Researchers estimate the total snow leopard population throughout its 13-country range at between 4,000 and 6,600 animals. About 60 percent of the population lives in China, particularly in the heart of the Tibetan Plateau and on the northern slope of the Himalayas.

However, snow leopard expert George Schaller of the New-York based NGOs Panthera and Wildlife Conservation Society writes in his 2016 book Snow Leopards, “such nebulous estimates are not surprising because many mountain ranges have been sampled at only a site or two, and no long-term monitoring of populations, lasting a decade or more, has been done to measure such dynamics as their birth and death rates.”

Between the 1950s and the 1980s, snow leopards suffered from severe poaching for their skin and bones. In 1989, China enacted its first ever Wildlife Protection Law, which categorized the snow leopard as a first class national level protected animal. Under the new law, local governments across the country began confiscating rifles, which contained the illegal poaching of the snow leopard and other wildlife.

Around the same time the government began establishing protected areas that include parts of the snow leopard’s range, such as Xinjiang Tumur Peak National Natural Reserve (established in 1985), Gansu Qilianshan National Natural Reserve (1987), Chang Tang National Natural Reserve in Tibet (1993), and Qinghai Sanjiangyuan National Natural Reserve (2000).

According to an October 2016 report titled An Ounce of Prevention: Snow leopard crime revisited from the UK-based NGO TRAFFIC, despite the fact that “hundreds of the endangered big cats are being killed illegally each year across their range in Asia’s high mountains,” the protection of the species in China is improving, and “the number of snow leopard skins seen openly for sale in markets by researchers has fallen markedly, particularly in China.”

Song Dazhao from the NGO Chinese Felid Conversation Alliance told Mongabay that compared with the other three wild big cat species in China — Amur tiger (Panthera tigris ssp. altaica), leopard, and clouded leopard (Neofelis nebulosa), the snow leopard is the most abundant and enjoys the best living conditions with the fewest human and natural threats.

Over the past 60 years habitat loss and poaching have pushed the other three cat species toward extirpation in China. Snow leopards, on the other hand, have avoided these threats due to their unique habitat in the country’s sparsely populated hinterlands.

Schaller writes of snow leopards “the cat needs landscapes, parts of which consist of protected core areas for all species, and the rest devoted to achieving a measure of ecological harmony between habitat, wildlife, and communities with their livestock.”

The Sanjiangyuan region is a strong example of this landscape approach. However, with climate change, considerable snow leopard habitat may be lost because of an upward shift in the tree line and concomitant loss of the alpine zone.

In addition, illegal poaching, particularly retaliatory and non-targeted poaching, continues to threaten local snow leopard populations in China. According to domestic public media reports, in January 2017 alone, three snow leopards were found in hunters’ traps in Qinghai. A 2014 article in the journal Biological Conservation found via household interviews that 11 snow leopards were killed each year in the Sanjiangyuan region alone, a number equivalent to about 1.2 percent of the estimated snow leopard population there.

Wang Peng, a wildlife film director who recently showed a cut of his new film Saving Snow Leopards at the New York WILD Film Festival in Shanghai, told the Chinese news outlet The Paper that on several occasions he witnessed snow leopards being trapped by Tibetan nomads in retaliation for killing livestock. According to Wang, he has spent over 14,000 Yuan ($20,300) to save five snow leopards from Tibetan nomads in the Sanjiangyuan region and elsewhere.

The number of livestock in the region is increasing, and people have begun herding them in even the most remote areas on the plateau. This has encroached on habitat for wild ungulates, resulting in a shortage of prey for snow leopards. “The biggest challenge facing snow leopards currently is its shrinking territory and reduced food resources caused by overgrazing,” Wang told The Paper.

Conflict resolution

A snow leopard preys on a yak in March 2016. Photo courtesy of Shanshui Conservation Center.

Herders in Sanjiangyuan National Park whom Mongabay interviewed last August all said they had lost livestock to snow leopards and other large carnivores.

Carnivores can indeed impose significant costs on residents of Sanjiangyuan National Park, where pastoralism is the dominant livelihood. One study indicated that wolves (Canis lupus), lynx (Lynx lynx), and snow leopards are the major livestock predators in most parts of the region. However, only sporadic studies on human-snow leopard conflicts have been conducted inside China, so not much is known about how many livestock the cats kill.

Even so it was clear the government needed to step in to ease tensions for the sake of both people and snow leopards in the new park. In 2016, the local government of Zaduo, a county in the upper reaches of the Mekong River, and SCC, the conservation organization, jointly set up a human-carnivore conflict insurance fund. They chose Niandu village inside Sanjiangyuan National Park as a pilot project for the fund.

According to Zhao Xiang from SCC, herders, the local government, and SCC jointly invest in the fund. Each household can choose to pay an annual insurance fee of three Yuan ($0.43) per yak, which amounts to an annual contribution of 25,652 Yuan ($3,719) from the village as a whole. The village elected representatives to serve as auditors for evaluating claims of livestock losses to carnivores. Zhao told Mongabay that the self-governed compensation fund effectively avoids herders making false allegations.

He also said the fund is helping herders avoid losses to carnivores. “According to our study, the period from December to April is normally the peak time for snow leopards preying on livestock. So we recommend that all herders enhance their supervision of their cattle during this particular time of the year,” Zhao said, adding, “positive changes are evident so far.”

Statistics indicate that while Niandu village lost 300 yaks in 2015 and more than 100 yaks in 2016, from January to April of this year only 17 compensation claims were made. At the same time, long-term infrared cameras monitoring wildlife in a roughly 2,000-square-kilometer (770-square-mile) area surrounding Niandu showed that during the past three years the local snow leopard population has held steady at 13 or more individuals.

The success of the human-carnivore conflict insurance fund in Niandu led Sanjiangyuan National Park’s management bureau to expand the program to other communities inside the park. The bureau recently distributed 300,000 Yuan ($43,500) to start insurance funds in other areas.

“The significance of the pilot program of the human carnivore conflict fund in Niandu, in my eyes, is more than pure compensation,” Zhao said. “It is rather an achievement by local indigenous people’s participation and the extension of their own traditional culture.”

“From this, we as researchers can also draw inspiration on how to help humans and wildlife peacefully coexist,” he said.

A snow leopard in the Sanjiangyuan region of China’s Qinghai province, captured by camera trap. Photo courtesy of Shanshui Nature Center.

For the rest of this article please go to source link below.