Bangladesh’s air pollution problem grows, brick by brick

Though only a small part of the nation’s GDP, brickmaking plays an outsized role in the spread of air pollution — and disease — in Dhaka and beyond.

Making bricks is serious business in Bangladesh. While exact numbers are hard to come by, estimates suggest the industry here employs more than one million people who churn out 23 billion bricks each year at some 7,000 kilns. Demand for bricks, too, is on the rise, following the growth of the construction industry amid an infrastructure boom.

DHAKA, BANGLADESH

But whatever the dividends those kilns deliver to this rapidly developing country, the thousands of slender, cylindrical chimneys attached to them exact a heavy and offsetting toll. They punctuate the horizon in cities and towns across Bangladesh — including some 1,000 in the suburbs of the nation’s capital, Dhaka — and they contribute mightily to what is considered some of the worst air pollution in the world.

“The air that touches my skin feels extremely dirty,” said university student Scionara Shehry, “so I use a scarf all the time to shield my hair and face from it when I’m on the roads.”

She is far from alone. During the dry season, when brickmaking is going full tilt, dust and smoke from wood- and coal-fired kilns mingle with clouds of pollution rising from trash fires and vehicle engines, hanging over the city like fog. The kiln operations alone — while representing just 1 percent of the country’s GDP — generate nearly 60 percent of the particulate pollution in Dhaka, according to Bangladesh’s Department of Environment (DOE). Many of those kiln operations — including some 530 sites producing more than 2 billion bricks annually in northern Dhaka — are so-called fixed-chimney kilns, which use inefficient technology with little to no pollution controls.

And these represent only the brickmaking businesses that regulators have managed to count. An untold number of other, haphazardly regulated brickmakers churn heavy clouds of smoke and dust skyward each year.

Worldwide, ambient particulate matter ranks as the sixth leading risk factor for premature death, according to the 2018 “State of Global Air” report, produced by the research nonprofit Health Effects Institute in Boston and the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington in Seattle. Those risks are particularly acute in Dhaka, where fine particle pollution like PM2.5 — microscopically small at 2.5 micrometers in diameter or less and a byproduct of combustion — is relentlessly inhaled by residents.

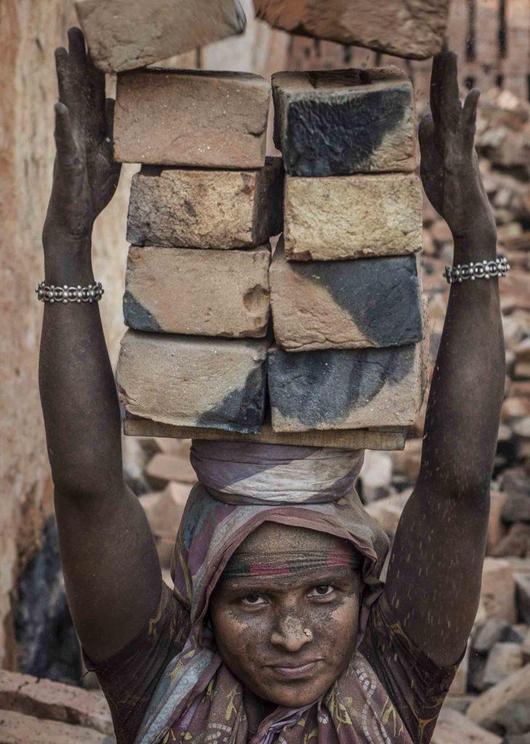

Workers carry bricks after they are formed and stack them in preparation for firing. Roughly one million people are employed in Bangladesh’s brickmaking facilities, which generate nearly 60 percent of the particulate pollution in Dhaka. Larry C. Price

Here, laborers sift through the ashes of a previous kiln firing to prepare the area for a new batch of bricks. People who work in or live near brickfields with coal- or wood-fired kilns, one researcher estimates, are 10 to 20 times more likely to suffer lung diseases than those who don’t. Larry C. Price

Massive piles of coal are frequent playgrounds for young Dhaka residents. Cleaner-burning and more efficient kiln designs have been developed, but the economic realities of conversion have slowed industry reform here. Larry C. Price

Patients wait to see doctors at the Asthma Center of the National Institute of Diseases of the Chest and Hospital in central Dhaka. Larry C. Price

Dr. Ferdous Wahid, right, examines a chest x-ray. “This makes me alarmed,” one Dhaka resident said of the city’s pollution, “thinking how much of the dust is settling in my lungs.” Larry C. Price

A lung specialist listens to the raspy breathing of a patient. Dr. Wahid says asthma is the most common pollution-related disease he sees. Larry C. Price

The World Health Organization ranks Dhaka among the top 50 out of almost 3,000 cities with the highest annual mean concentrations of PM2.5, which is considered a potent and efficient killer. In winter, the city’s daily PM2.5 levels can soar well above 200 micrograms per cubic meter — eight times the level WHO considers safe. Exposure to PM2.5 has been linked to lung cancer and other health problems, and at least one study suggests that it claimed 14,000 lives in Greater Dhaka in 2014. Two years later, researchers estimated that it was responsible for the deaths of more than 100,000 Bangladeshis nationwide.

“My furniture gets covered in a layer of dust particles within a few hours of cleaning it,” said one North Dhaka homemaker, “and this makes me alarmed thinking how much of the dust is settling in my lungs.”

The Bangladeshi government operates 11 continuous air monitoring stations throughout the country. Three stations are in Dhaka, two in Chittagong, and one in each of the country’s other six divisions. The Department of Environment monitors and reports findings daily for six common pollutants, including PM2.5, PM10, nitrous oxide, sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, and ozone.

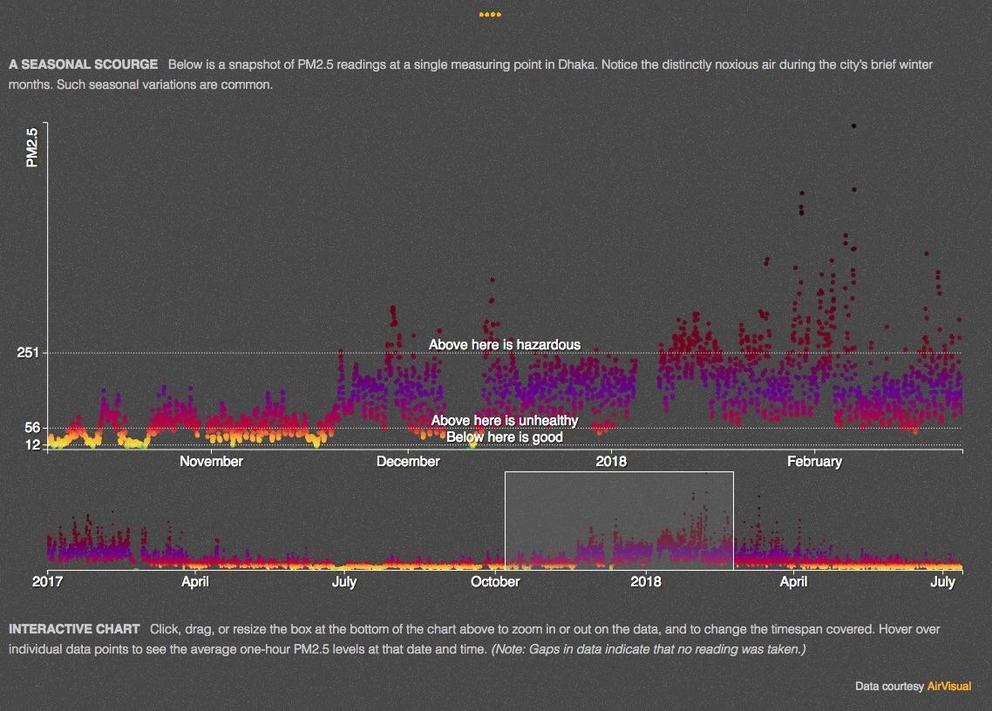

According to air quality data from 2017, nearly half of Dhaka’s available hourly readings were at or above unhealthy levels — and brick kilns contribute significantly to PM2.5 concentrations in the cities close to where they operate. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency considers the daily concentration of PM2.5 to be unhealthy for anyone at levels above 55.4 micrometers per cubic meter of air and readings well above this are common. Since 1990, annual average population-weighted PM2.5 levels in Bangladesh have increased from around 65 micrometers per cubic meter in 1990 to 101 in 2016, according to the State of Global Air report.

A SEASONAL SCOURGE Below is a snapshot of PM2.5 readings at a single measuring point in Dhaka. Notice the distinctly noxious air during the city’s brief winter months. Such seasonal variations are common.

INTERACTIVE CHART Click, drag, or resize the box at the bottom of the chart above to zoom in or out on the data, and to change the timespan covered. Hover over individual data points to see the average one-hour PM2.5 levels at that date and time. (Note: Gaps in data indicate that no reading was taken.)

Data courtesy AirVisual

While traffic and burning trash are major contributors to the foul air, it is hard to miss the consequential impacts of the brick kilns. Workers travel from around the country to Dhaka’s brickmaking operations, often bringing their families with them to work from October into March. Men and women carry heavy loads of bricks on their heads, amid swirling clouds of dust, and it is common to see young children toiling at the edges of the brick-drying fields.

Mohammad Esarul Molla, 28, and Mahuda Akter, 22, came to the brick fields with their two young children. Laborers, the couple works eight hours a day in the brick fields. Molla earns $2 to $3 a day for his efforts. Akter brings in just under $1 a day. Like many of the itinerant laborers here, they accept the conditions they must work in.

“I don’t think the work in the brick field is dangerous,” Molla said. “I haven’t faced any breathing problems or had any diseases from working here so far, as the smoke goes up through the chimney and doesn’t come to ground level.” Akter even says she likes the work, which provides needed income for her family.

Ripa, a young mother in her 20s who gave only a first name, said she has been working at a brick kiln for five or six years. While she says she notices the dust around her, she insists it doesn’t cause any health problems. Masudur Rhaman, of Ibrahim Medical College in Dhaka, however, estimates that those who work in or live near brickfields with coal- or wood-fired kilns are 10 to 20 times more likely to suffer lung diseases than those who don’t. “Working in dust particles [from kilns] is an occupational hazard,” he said.

TWO VIEWS OF BRICK KILNS: FROM THE SKY & ON THE GROUND

In the first video below, drone footage captures a typical Bangladesh kiln operation, where formed bricks are stacked, covered, and then coal-fired in elongated trenches that encircle a central exhaust stack. Below that, a 360-degree video reveals workers tending to various aspects of the brickmaking process on the ground. Click and drag the video screen to explore the environment up close.

(video can be accessed at source link below)

(video can be accessed at source link below)

Legislation passed in 2013 aims to prevent new kiln construction in residential, agricultural, and environmentally sensitive areas and convert the standard kiln model, which features an oval firing chamber with a chimney in the middle, into something deemed more efficient. While this often means upgrading to a zigzag kiln design, where bricks are stacked in a rectangular circuit to form chambers guiding the heated air around them, no concrete standards exist for what this must do for emissions. Rather, according to the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), the Government of Bangladesh uses technology-based standards, as opposed to emissions-based, to determine if a kiln can be considered environmentally-friendly.

If constructed properly, zigzag kilns do improve efficiency and can potentially reduce particulate emissions by 80 percent or more. But due to a lack of proper resources, skill, and regulatory authority, as well as low-level corruption within the Department of Environment, it’s likely that few have been satisfactorily upgraded.

Still, officials are encouraging kiln operators to make the switch, and say they no longer issue environmental clearance certificates to new kilns that use the traditional methods to fire bricks.

“In eight to 10 years we will phase out or close all the conventional kilns,” said Ziaul Haque, deputy director of law at the Department of Environment, adding that the government also plans to limit the number and size of new kiln facilities.

Munjurul Hannan Khan, a representative of the Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change and director of the agency’s Clean Air and Sustainable Environment project, suggested oversight is improving. “We are monitoring [the conversion of brick fields] closely and discouraging unregistered brick kilns from operating in the area,” he said. The ministry oversees environmental clearance for old brick fields, monitors compliance, and fines or closes non-compliant brick kilns, Hannan Khan added.

During seasonal operations, brick factories like the MEB facility can produce millions of bricks. The season usually begins in late fall or early winter. Larry C. Price

The fuel for the coal-fired kilns is sourced from Africa, Indonesia, and Russia. Larry C. Price

Workers like Mohammad Esarul Molla, 28, and his daughter Moumita, age 6, reside in huts on the factory property. While the air is often hard to breathe, the job is welcomed. Larry C. Price

According to a Department of Environment report, 4,390 kilns in the country were using modern technology as of last year, and about 65 percent of the facilities had been converted to environmentally-friendly versions. The department also reported that it fined 605 illegal brick kilns between 2013 and 2017 and closed or dismantled 32. But with only vague wording to describe its updates, the state of the country’s “modern” or “environmentally-friendly” kilns is far from clear. In her experience with brick kilns in neighboring India, Cheryl Weyant, a Ph.D. student in environmental engineering at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, says the implementation of less-polluting technology is in the “very beginning stages.”

While the 2013 legislation officially banned traditional brick kilns and placed restrictions on where new facilities could be built, many brickmakers say they’d go out of business if they followed all the rules.

“We are not against protecting the environment,” said Abu Bakr, secretary general of the Bangladesh Brick Manufacturing Owners Association, “but if this act is implemented it won’t be possible to have brick kilns anywhere in the country and millions of people working in this industry will become jobless.”

In a 2017 interview with The Daily Star, Bangladesh’s leading English-language newspaper, Raja Shankar, described as another kiln business representative, said that kiln conversion can cost from $96,000 for the simplest model to $6 million for the most advanced.

“Because brick-making is not recognized as a formal industry in Bangladesh, [kiln owners] are not eligible for concessional loans of financial institutions for small and medium enterprises,” said Tanvir Ahmed, an environmental specialist with World Bank Bangladesh. According to a joint report from UNDP and the Bangladesh DOE, brickmaking here is better described as a “semi-formal” industry due to factors including its seasonal employment, outdated technology, and lack of large-scale cooperation.

Without access to needed financial assistance, as well as the barrier of existing on leased land, thousands of kilns continue to operate illegally without upgrading their production process, Ahmed said.

To reduce PM2.5 and other emissions from brick kilns in a meaningful way, environmentalists say the Bangladesh government must enforce laws more stringently, recognize brickmaking as a formal industry, and promote financial policies to support kiln conversions.

“We know a lot,” said Atiq Rahman, executive director of the nonprofit Bangladesh Center for Advanced Studies, referring to the impacts of particulate pollution, “but knowledge is not enough.”

Larry C. Price

Larry C. Price

Four-year-old Nayem often plays atop large piles of coal used to fire kilns at a brick factory at the edge of Dhaka, Bangladesh. The chimneys from such factories contribute to some of the worst air pollution in the world. Larry C. Price

Video can be accessed at source link below.