Activists urge end to South Korean funding of Indonesia coal plants

Environmental activists in Indonesia have called on South Korean funders to withdraw their support for new coal-fired plants that they warn will be the most polluting in the Southeast Asian country.

The Suralaya power complex, about 100 kilometers (60 miles) west of the capital, Jakarta, already has eight coal-fired plants in operation, churning out 3,400 megawatts, or 18 percent of the electricity for the islands of Java and Bali.

The government plans to add two more plants, with a generating capacity of 1,000 MW each, as part of the infrastructure-centered economic development policy being pushed by the administration of President Joko Widodo.

Funding for the new plants, billed at $1.67 billion, will come from loans from the Export-Import Bank of Korea (KEXIM), the Korea Development Bank (KDB Bank) and the Korea Trade Insurance Corporation (K-sure).

Greenpeace Indonesia energy campaigner Didit Haryo said the group had sent an open letter appealing to the South Korean institutions to “immediately withdraw” their funding for the project.

“The impact of the new plants is too big and is very bad for their investments,” he said. “We’re urging them to think about investing their money in renewable energy projects instead.”

Greenpeace Indonesia also sent the letter to the South Korean Embassy in Jakarta; none of the recipients had responded as of Nov. 9, Didit said.

Suralaya coal power plants. Image by Satari/Wikimedia.

Pollution problem

The project’s South Korean connection comes from the consortium picked to build the new plant, comprising Indonesian state-owned contractor PT Hutama Karya and its South Korean partner, Doosan Heavy Industries and Construction.

The Suralaya complex is run by PT Indo Raya Tenaga, also known as Indonesia Power, one of the country’s few independent electricity producers. Indonesia Power and the contracting consortium signed the agreement for the expansion project on Sept. 10 in Seoul.

The complex is already the single-biggest electricity generator in Indonesia, burning through 35,000 tons of coal a day, and was built primarily to serve the steel mills and heavy industries nearby.

Because of its sheer output, Suralaya emits more nitrous oxides, or NOx, than any other power facility in Southeast Asia, according to satellite data analysis by Greenpeace. Nitrous oxides are a class of compounds that contribute to air pollution and harm human health.

The pollution from Suralaya is particularly bad because when the first set of plants came online in 1984, there were no regulations or technology in place to limit NOx emissions, Didit said.

“Even before the two new plants are added to the power complex, the Suralaya power plants already emit the highest level of NOx pollutants in Java,” he said.

Greenpeace’s analysis showed that pollutants from Suralaya travel as far as the Greater Jakarta area, which, with a population of more than 30 million, is the biggest metropolitan area in Southeast Asia.

“Imagine if two more units, each of 1,000 megawatts, are added,” Didit said. “It won’t just be the people in Suralaya who will be affected. People in Jakarta will also be affected, because right now the pollution from the existing plants already reaches Jakarta. So clearly the amount of pollution reaching Jakarta will be even greater.”

He said it should be clear to the South Korean institutions that their support for the Suralaya expansion project bore great risks.

“By continuing to finance coal plants in Indonesia, your institutions are committing our planet to extreme climate change and are also committing the citizens of Indonesia to death and illness as a result of air pollution from new coal-fired power plants,” the activists said in their open letter.

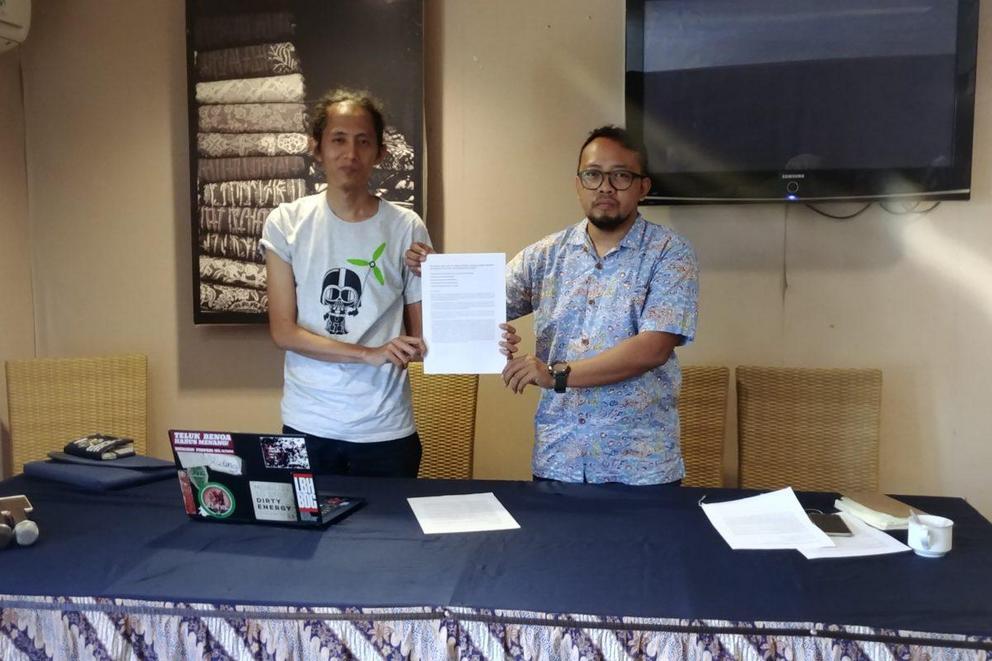

Campaigners from Greenpeace Indonesia and Walhi hold an open letter addressed to South Korean investors and embassy in Jakarta, Indonesia. Image by Hans Nicholas Jong/Mongabay.

Risky investment

Greenpeace is also arguing its point from a financial perspective. Any investments in new power plants in Indonesia, it says, is already inherently risky because of the weakening of the country’s currency, the rupiah.

The rupiah is the second-worst performing currency in Asia this year, behind only the Indian rupee, sliding 9 percent against the U.S. dollar so far this year. Indonesia is among several emerging markets struggling with a current-account deficit and capital flight, prompted initially by Turkey’s lira crisis.

The weakening of the rupiah has increased the cost of imports, prompting the government to tighten import controls. One of the sectors affected is energy: up to 80 percent of the components needed to build power plants have to be brought in from overseas.

In September, the government announced that it would delay construction of 15,200 MW of power plant projects that would have required the import of $10 billion worth of equipment. Most of the affected projects are in Java, including the Suralaya expansion project, which is now slated to fall under the government’s 2021-2026 development plan, instead of the current five-year plan.

Critics have also questioned the government’s power-plant building spree, which it has had to scale back from its initial aim of adding 35,000 MW of generating capacity to the national grid by 2019. The original target assumed electricity consumption would increase by 8 percent a year; so far this year, it’s only grown by 4.7 percent, and isn’t projected to exceed 6 percent by the end of the year.

“This means that these projects are not needed to meet energy needs in our country and should be cancelled,” Greenpeace said in its letter.

Green activists protest at a coal-fired power plant in Cirebon city, West Java, against Indonesia’s electricity project that heavily depends on the fossil fuel. Image by Afriadi Hikmal/Greenpeace.

End of coal

The South Korean banks’ financing of the Suralaya expansion project bucks a rising trend worldwide in which governments and financial institutions are divesting from fossil fuel projects.

Several countries have committed to phasing out their coal-fired power plants for renewable alternatives, including China, the world’s biggest consumer of the fossil fuel. Financial institutions such as Deutsche Bank, Danske Bank, Allianz and Dai-ichi Life are also either ending or restricting their funding and underwriting of coal projects.

The latest company to join the movement is Standard Chartered Bank, which announced last month that it would no longer fund coal-fired power plants. Since 2010 it has loaned $1.8 billion for coal power projects.

Greenpeace said the South Korean institutions’ support for Suralaya put it at odds with South Korea’s own domestic coal policy. Chungnam province, home to half of the operating coal plants in the country, has joined an alliance of governments committed to phasing out coal, called the Powering Past Coal Alliance.

Chungnam, the first province in Asia to join the alliance, announced the early shutdown of 15 aging coal plants by 2025, and a complete phase-out of the fossil fuel by 2050.

Two South Korean pension funds — the Korean Teachers Pension and the Government Employees Pension System — also recently announced their divestment from coal, with plans to boost existing stakes in renewable energy projects and make investments in new ones.

“We’re witnessing the beginning of the end of coal in [South] Korea through game-changing decisions by Chungcheongnam-do [Chungnam province] to phase-out coal and two South Korean pension funds to end coal financing,” Greenpeace East Asia climate and energy campaigner Mari Chang said. “These decisions challenge the Moon government to also ramp up action in line with the Paris goals.”

Ending the world’s reliance on coal is seen as crucial to have a real chance at limiting global warming to less than 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit). Global carbon dioxide emissions must be halved by 2030 before falling to net zero by mid-century, at the latest, to stay within that limit, according to a special report by the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) at a meeting in South Korea in October.

For that to happen, global coal power use has to fall by two-thirds by 2030 and be almost fully phased out by 2050. Renewables can fill the gap, supplying 70 to 85 percent of the world’s electricity by 2050, or potentially even more.

“The IPCC report has sent a clear signal that coal must not be part of our future,” Chang said. “This means [South] Korea’s top public financial institutions — KEXIM, K-sure, and KDB Bank — must end their overseas coal investments.”

If there are to be no more coal power plants by 2050, it makes little sense to start building a new one now, given it will have a lifespan of less than 30 years, said Dwi Sawung, an energy campaigner with the Indonesian Forum for the Environment (Walhi).

“It’ll be such a waste to have a new plant shortly before it has to be retired,” he said.

Locals who are affected by coal power plants around Indonesia gather during a protest in front of the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources office in Jakarta, Indonesia. They’re demanding the government to switch from coal to renewable energy. Image by Hans Nicholas Jong/Mongabay.

For full references please use source link below.