18 new species of spiders that look like pelicans

Once thought extinct, the pelican spiders of Madagascar turn out to be highly diverse.

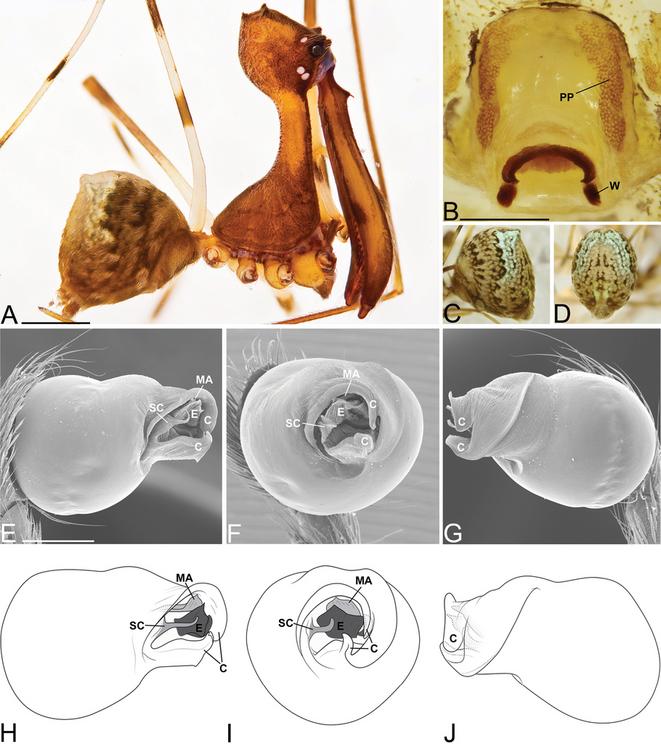

Eriauchenius milajaneae is one of the 18 new species of pelican spiders from Madagascar described by the scientists. This species was named after Hannah Wood's daughter, and is known only from one remote mountain in the southeast of Madagascar.

There are wolf spiders (family Lycosidae), mouse spiders (Missulena occatoria), lynx spiders (family Oxyopidae), and peacock spiders (Maratus pavonis) – all of which are found in Australia – but some of the most unusual arachnids around are pelican spiders, from the family Archaeidae. Also known as assassin spiders, they are found in Australia, South Africa – and Madagascar, where researchers have recently discovered 18 new species.

Hannah Wood, curator of arachnids at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, in Washington DC, US, has examined and analysed hundreds of pelican spiders found in the field in Madagascar and preserved in museum collections. Her analysis, focusing on spiders of the Eriauchenius and Madagascarchaea genera, sorted the spiders into 26 different species – most of which have never before been described.

Wood and colleague Nikolaj Scharff, from the University of Copenhagen, detail all 26 pelican spider species in the journal ZooKeys.

All of them live only in Madagascar, an island with tremendous biodiversity threatened by widespread deforestation. The new species add to scientists' understanding of that diversity, and will help them investigate how pelican spiders' unusual traits have evolved. They also highlight the case for conserving what remains of Madagascar's forests, Wood says.

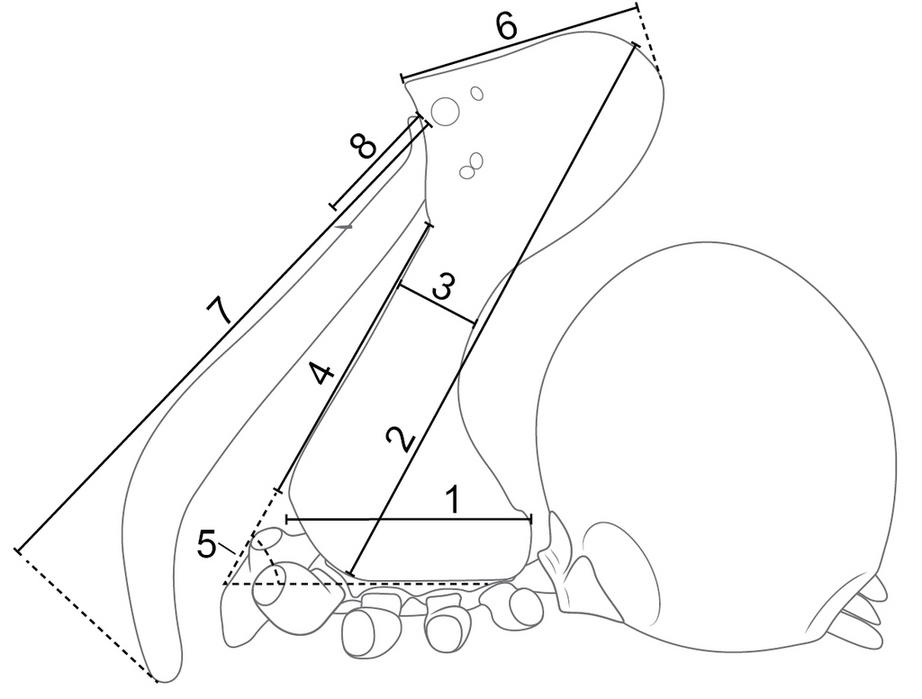

The pelican spider gets its name from an unusual modification to its cephalic area: its shell is extended and tubular in structure, and encircles the mouthparts, giving it the appearance of a neck and head.

The spiders do not build a web to capture their prey. Instead, they are active hunters – hence the name “assassin” – feeding exclusively on other spiders. The highly modified head and carapace allows for extremely manoeuvrable jaws that can be extended 90 degrees away from the body to attack spider prey at a distance.

Today's pelican spiders are “living fossils”, Wood says, remarkably similar to species found preserved in the fossil record from as long as 165 million years ago.

Because the living spiders were found after their ancestors had been uncovered as fossils and presumed extinct, they can be considered a “Lazarus” taxon, risen from the dead.

Wood says fossilised remains of pelican spiders have turned up in the northern hemisphere but the distribution pattern of living examples – Madagascar, South Africa and Australia – suggests their ancestors were dispersed to these landmasses when the earth's supercontinent Pangaea began to break up around 175 million years ago.

In 2000, the California Academy of Sciences launched a massive arthropod inventory in Madagascar, collecting spiders, insects and other invertebrates from all over the island.

Wood used those collections, along with specimens from other museums and spiders that she collected during her own field work to conduct her study.

Wood says there are almost certainly more spiders to be discovered. "I think there's going to be a lot more species that haven't yet been described or documented," she says.