The Tollund man spills his guts: new analysis of bog body’s last meal

Top image: The well-preserved head of the Tollund Man.

There has long been an obsession with final-menu fantasies, as evidenced by the amount of literature dedicated to last meals on death row in the United States. Now, researchers in Denmark have returned to study the famed Tollund Man’s last meal using cutting-edge technology in the hope of learning more about life in Iron Age Denmark.

Location where the Tollund Man bog body was discovered.

Location where the Tollund Man bog body was discovered.

Who Was the Tollund Man?

In 1950, while working cutting peat in the Bjaeldskov bog about 10 kilometers (6.2 miles) west of Silkeborg in Denmark, the brothers Viggo and Emil Hojgaard came across a man’s body with a “face so fresh they could only suppose they had stumbled on a recent murder,” reported Smithsonian Magazine . So much so that they called the police. Further analysis however concluded that the body was a remnant from another era.

Dubbed the Tolland Man , the remains were of a 30 or 40-year-old male who lived some time between 405 and 380 BC. Found naked and with a leather noose around his neck, the man had been hung before being carefully placed in a sleeping position and buried in the bog. There he remained, preserved in the Scandinavian peat, for over 2,400 years.

Careful analysis revealed that the Tollund Man had not suffered injury or trauma, except for the hanging itself. His eyes and mouth had been delicately closed, creating the appearance of peaceful slumber. While Iron Age burials of this era involved cremation and placing a person’s ashes in an urn, the Tollund Man burial was different.

Archaeologists concluded that the Tollund Man was evidence of ritual sacrifice. The fact that he was killed in the winter or early spring (an aspect deduced from the seasonal contents in his stomach) and buried in a watery location, was seen as evidence for the sacrificial nature of his death. It is believed that early European people saw water as the primary interface for communicating with the gods and human sacrifices are said to have been made to the goddess of spring.

Discovered in 1950, the Tollund Man is now on display at the Silkeborg Museum in Denmark.

Discovered in 1950, the Tollund Man is now on display at the Silkeborg Museum in Denmark.

The Tollund Man, Bog Bodies and Preservation

“To the people who put him there, a bog was a special place,” explains Joshua Levine in Smithsonian Magazine . “Half earth, half water and open to the heavens, they were borderlands to the beyond.” The combination of ritual sacrifice and a bog landscape is an archaeologist’s dream come true due to the unique ability of bogs to preserve organic matter, including human bodies. Cold, acidic and oxygen-free, the wetland environment can provide information that can’t be found anywhere else, such as details related to appearance, everyday life or dress.

As with other bog bodies discovered in Northern Europe, archaeologists have continued to apply increasingly sophisticated technology to find out more about the Tollund Man. “The world’s most famous bog body ,” at least according to British YouTube personality Simon Whistler, has certainly garnered a lot of attention over the past few decades.

From a visit to the Paris Natural History Museum, where researchers scanned his feet in a micro CT-scanner to determine if he had warts and assess his arteries, to complex analysis of strontium isotope in his hair, with the aim of tracing the locations to which he travelled in his lifetime. He’s also been the subject of complex photo shoots .

Bizarrely, his toe was even stolen and carried around for decades by a famous conservator Børge Brorson Christensen, before being returned after Christensen’s death. At least that’s the story told by the Silkeborg Museum , where the Tollund Man is currently housed in central Denmark.

Photomicrograph of the gut contents of the Tollund Man.

Photomicrograph of the gut contents of the Tollund Man.

Learning From the Tollund Man’s Last Meal

For an era which left behind no written records, bog bodies are a fascinating source of information. When it comes to the Tollund Man, it wasn’t just that his face, skin and hair was preserved - his intestines were too! The analysis of his last meal isn’t just part of some morbid obsession. While last meals can provide details about sacrificial rituals, the study of gut contents can also provide remarkable information about daily life in Iron Age Denmark, such as diet, health and hygiene.

Back in 1950, archaeologists conducted forensic analysis of the stomach and intestines, which divulged the meal which the Tollund Man ate around 12 to 24 hours before his death. By identifying cereal grains and seeds, they concluded that he had eaten a porridge made up of of barley, flax and wild plant seeds. Nevertheless, the technology available didn’t allow them to study any of the less obvious ingredients or to quantify the meal.

Now, the new study has returned to re-analyze the gut contents, in the hope of distinguishing any “unusual ingredients” which could point to ritual practices, or even to find out more about food preparation 2,400 years ago. This was complex work, which used pioneering applications of modern-day technology, such as the use of pollen, NPP, macrofossil, steroid and protein analysis.

Using these techniques, they managed to reach some previously unknown verdicts. While the 1950s study had concluded that meat was not part of the Tollund Man’s diet, the new analysis found that fish, perhaps eel, was part of his last meal. The “fragmentation of the cereals and other seeds” also led them to believe that “these had been ground before being cooked,” while charred food crust remnants discovered in the gut suggest that the porridge was cooked in a clay vessel.

Reconstruction of the ingredients contained in the Tollund Man's last meal, shown in quantities relative to the intestinal contents under study. They include barley, pale persicaria, barley rachis segments, flax, black-bindweed, fat hen, sand, hemp nettle

Reconstruction of the ingredients contained in the Tollund Man's last meal, shown in quantities relative to the intestinal contents under study. They include barley, pale persicaria, barley rachis segments, flax, black-bindweed, fat hen, sand, hemp nettle

What the Tollund Man’s Gut Can Tell Us About Iron Age Life

The team even identified remnants of algal and wetland plant seeds, which could mean that the porridge was made using water from a lake, pond or bog. While no “magic” or hallucinogenic ingredients were discovered, they did find parallels with another bog body’s last meal, that of the Grauballe Man , as weed seeds formed a significant part of the meal. Future studies on other bog bodies may help define if these wild seeds were commonly used as part of special rituals, such as human sacrificial events. Keep in mind however that they may have been used simply for added flavor.

The study also focused on intestinal parasite eggs to learn about health and hygiene during his era. The Tollund Man’s gut was infected with three types of parasite. Evidence of whipworm and mawworm were seen as a sign of bad hygiene since they are known to spread due to contaminated water and food. Tapeworm could be evidence of consumption of raw or undercooked meat.

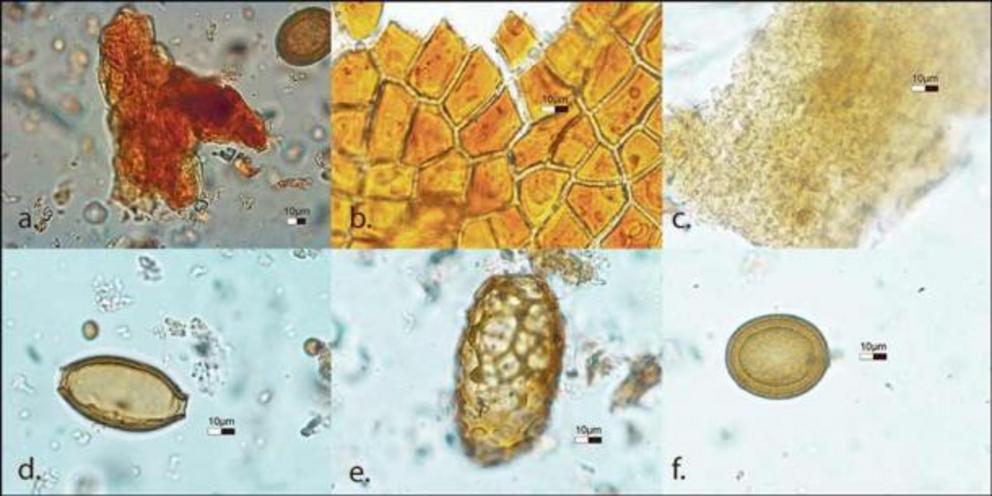

The contents of the Tollund Man’s gut include a) barley pollen, b) flax cells, c) barley cells, d) a whipworm egg, e) a mawworm egg and f) a tapeworm egg.

The contents of the Tollund Man’s gut include a) barley pollen, b) flax cells, c) barley cells, d) a whipworm egg, e) a mawworm egg and f) a tapeworm egg.

Surprisingly “the meal probably differed little from the present-day recommended intake of 10-20 percent protein, 55-60 percent carbohydrates and 25-30 percent lipids.” This suggests that this was not a time of severe food shortage.

The Danish scientists have published the results in a new article due to be published in Antiquity. In their own words, the results highlight the way “new techniques can throw fresh light on old questions and contribute to understanding life and death in the Danish Early Iron Age.” The new evidence, gleaned from the Tollund Man’s gut contents, provides a pretty successful argument for why archaeologists should consider returning to bog body remains after decades in storage or on display in museums around the world.Application of new and more precise techniques can provide crucial data about the past. The prehistoric belief that bogs were “borderlands to the beyond” could hardly be more apt. The study of the bog-preserved Tollund Man continues to provide us with information and to fill in the gaps regarding our Iron Age history.