Study demonstrates terrible toll of sixth century plague of Justinian

Top image: St. Sebastian pleads for those afflicted with plague during the 7th century Plague of Justinian in a painting by South Netherlandish painter Josse Lieferinxe.

In a new study appearing in the journal Past & Present , Cambridge University history professor Peter Sarris argues that recent scholarship has badly underestimated the true impact of the sixth-century Plague of Justinian on Eurasian and North African societies. To prove his case, Sarris assembled a record of developments that occurred during this earliest known manifestation of the bubonic plague in the west, developments that signaled the arrival of a massive societal crisis in the Byzantine-era world.

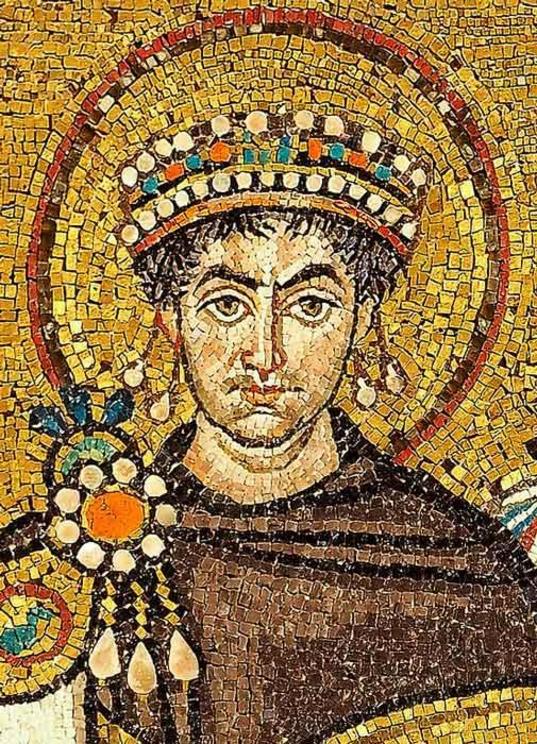

Detail of a contemporary portrait mosaic of Emperor Justinian I after whom the Plague of Justinian is named, in the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna.

Detail of a contemporary portrait mosaic of Emperor Justinian I after whom the Plague of Justinian is named, in the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna.

The Plague of Justinian Lasted More Than 200 Years!

Nearly 800 years before the Black Plague wiped out at least one-third of the population of Europe, the Plague of Justinian began its deadly circular march around the Mediterranean Sea’s 28,600 miles (46,000 kilometers) of coastline. Both disease outbreaks were caused by the same bacterial agent ( Yersinia pestis ), which was carried by a type of flea common to rats.

The Plague of Justinian was so named because the first outbreak occurred at a time when the Byzantine Emperor Justinian was attempting to restore the Roman Empire to its past glory. The initial 541—549 bubonic plague outbreak undoubtedly did much to frustrate his efforts, forcing him to take emergency measures simply to preserve what he already had.

Unlike the Black Plague, which lasted for seven years before ending, the Plague of Justinian included a series of bubonic disease outbreaks that extended over a 200-year period, beginning in 541 AD and ending in approximately 750 AD. The nations of Europe, North Africa, and the Near East that surrounded the Mediterranean experienced a high death toll as a result of this plague, along with other effects that highlighted the relentless and devastating nature of this long-term recurring crisis.

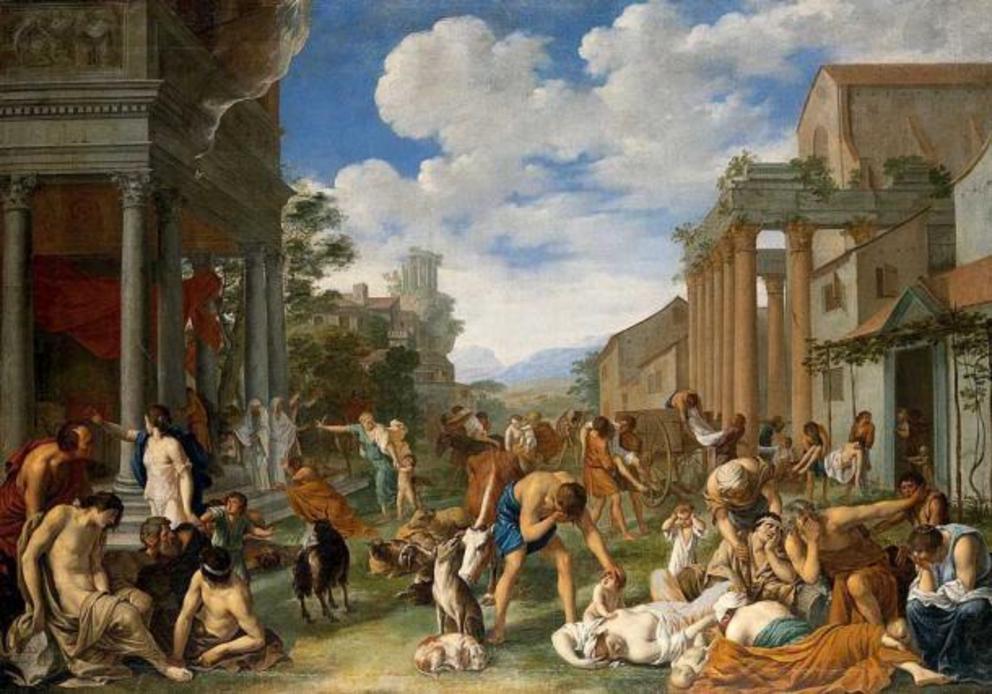

The plague of the Philistines at Ashdod by Pieter van Halen, which is described in the Old Testament, I Samuel 5, 5-6.

The plague of the Philistines at Ashdod by Pieter van Halen, which is described in the Old Testament, I Samuel 5, 5-6.

Was the Plague of Justinian Really that Bad?

In recent years revisionist scholarship has begun to call into question the true nature and impact of plague. Studies published in 2019 and 2020 concluded that the impact of the bubonic plague outbreaks of the sixth-through-eighth centuries in Eurasia had been overestimated. One such study referred to the plague as an “inconsequential pandemic,” while another compared the Plague of Justinian to a modern flu outbreak.

Some reached their conclusions based on the fact that only a few pieces of ancient literature actually discussed the plague. Countering this argument, Professor Sarris pointed out that the ancient sources that did mention the plague highlighted its severity.

“Witnessing the plague first-hand obliged the contemporary historian Procopius to break away from his vast military narrative to write a harrowing account of the arrival of the plague in Constantinople that would leave a deep impression on subsequent generations of Byzantine readers,” Sarris said, in a University of Cambridge press release that discussed his study. “That is far more telling than the number of plague-related words he wrote.”

In addition to such textual references, Sarris identified developments on the Byzantine legislative front during Justinian’s reign as emperor that were likely responses to the impact of the deadly plague.

Between 542 and 545, Justinian instituted several legal reforms that suggested a crisis was unfolding. For example, in 542 the emperor took actions to guarantee the stability and survival of the Byzantine banking sector. He wrote that he was doing so to counteract the effects of an “encircling presence of death” that had “spread to every region.”

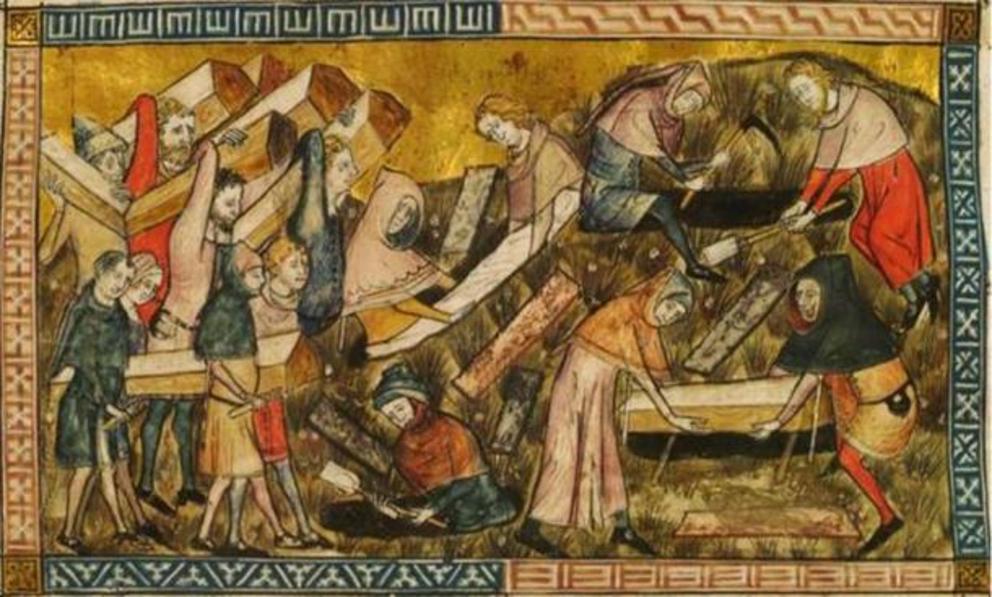

Citizens of Tournai, Belgium bury plague victims. Miniature by Pierart dou Tielt.

Citizens of Tournai, Belgium bury plague victims. Miniature by Pierart dou Tielt.

Simultaneously, Justinian expanded the empire’s money supply by reducing the weight of gold and copper coins to make them easier to mint. This action was likely intended to stimulate a contracting economy , which would have seen a reduction in production and consumption caused by high death tolls and quarantines. The change might also have helped the empire cover administrative costs and meet its financial obligations.

In another emergency measure, in 544 the emperor instituted wage and price controls. Justinian claimed that this was in response to attempts by workers to exploit labor shortages for their own selfish benefit. He referred to the current trials as “chastening which has been sent by God’s goodness” and lamented the fact that workers “have turned to avarice” instead of becoming “better people.”

Unsurprisingly, there is nothing in the historical record that suggests Justinian asked aristocrats and nobles to make any financial sacrifices for the common good. Those types of demands were undoubtedly reserved for laborers and peasants.

Sarris believes Justinian’s actions only make sense if the plague of 541 was highly disruptive and did quite a bit of damage to the empire and its economy.

“What is most striking about the governmental response to the Justinianic Plague in the Byzantine or Roman world is how rational and carefully targeted it was, despite the bewilderingly unfamiliar circumstances in which the authorities found themselves,” Sarris said.

Such actions would have prevented the implosion of the empire, even in the face of an unprecedented public health crisis.

“The significance of a historical pandemic should never be judged primarily on the basis of whether it leads to the ‘collapse’ of the societies concerned,” Sarris declared. “Equally, the resilience of the East Roman state in the face of the plague does not signify that the challenge posed by the plague was not real.”

People who died of bubonic plague in a mass grave from 1720 to 1721 in Martigues, France.

People who died of bubonic plague in a mass grave from 1720 to 1721 in Martigues, France.

A Separate Plague Pathway to England

Genetic testing in recent years has proven that the Plague of Justinian was bubonic. Scientists have found traces of the Yersinia pestis DNA in early medieval skeletal remains found in England, France, Spain, and Germany.

One 2018 study of the bacteria’s DNA found that samples retrieved from the early Anglo-Saxon burial site of Edix Hill in Cambridgeshire were from the oldest known lineage of this deadly microbe. Given the distance that separates England from the Mediterranean, it seems likely that the bacteria arrived in England and the Mediterranean separately and independently. Scientists agree the disease originated in Central Asia, likely as far back in time as the Bronze Age (before 1,200 BC), which meant its initial carriers may have followed a variety of pathways in their migrations westward.

One possible interpretation of the 2018 study (mentioned by Sarris) is that the plague may have reached the Mediterranean from the Red Sea region, but arrived in England from farther north, specifically from the Baltic region and/or from Scandinavia. It may very well have arrived in England even before it reached the Mediterranean, which would be consistent with the latest genetic studies.

Sarris noted that the Justinianic Plague and the Black Plague were both preceded by large-scale invasions of nomadic forces from the east. It was the Huns who arrived in western Eurasia in the 4th and 5th centuries, and the Mongols who came in the 13th century. These groups may have been the carriers of a deadly and devasting illness, which likely killed between 100 million and 200 million people during its various outbreaks.

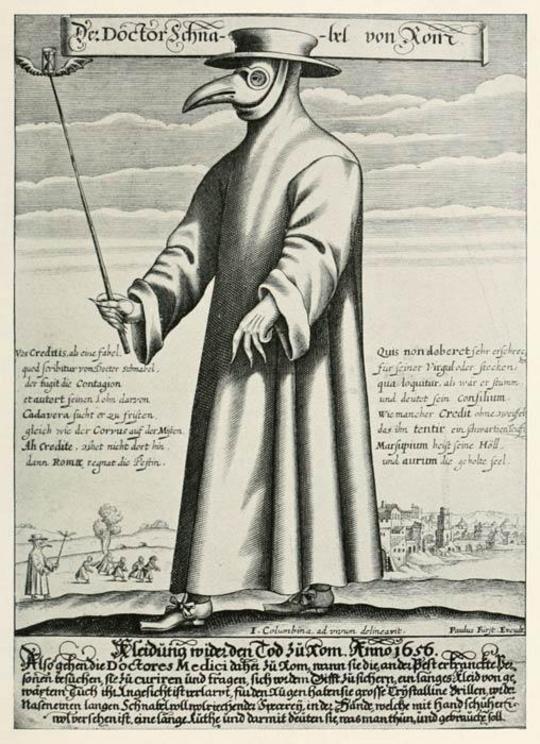

Copper engraving of a bubonic plague doctor from the 17th century. This is one of the most well-known representations in art of the Black Death.

Copper engraving of a bubonic plague doctor from the 17th century. This is one of the most well-known representations in art of the Black Death.

Parallels of Plagues and Pandemics

To explain the ongoing dispute over the severity of the Plague of Justinian, Sarris noted that many academics prefer to focus on internal factors that influence societal evolution.

“Some historians remain deeply hostile to regarding external factors such as disease as having a major impact on the development of human society,” he explained. “‘Plague skepticism’ has had a lot of attention in recent years.”

In Sarris’s opinion, the overall body of evidence shows that the Justinianic Plague, in both its initial and later waves, had a profound and meaningful impact on early medieval societies. It was a dynamic outside element that was suddenly and unexpectedly added to the equation, inevitably creating turmoil that significantly disrupted normal social, economic, and political functioning.

The parallels between the Plague of Justinian in the sixth century and the Covid-19 pandemic in the 21st is obvious. Despite the enormous amount of time that has passed, Sarris is convinced that our knowledge of the past could offer us some guidance today.

“We have a lot to learn from how our forebears responded to epidemic disease,” he concluded, “and [about] how pandemics impacted social structures, the distribution of wealth, and modes of thought.”