Sobekneferu’s legacy: the sacred places of Egypt’s first female pharaoh

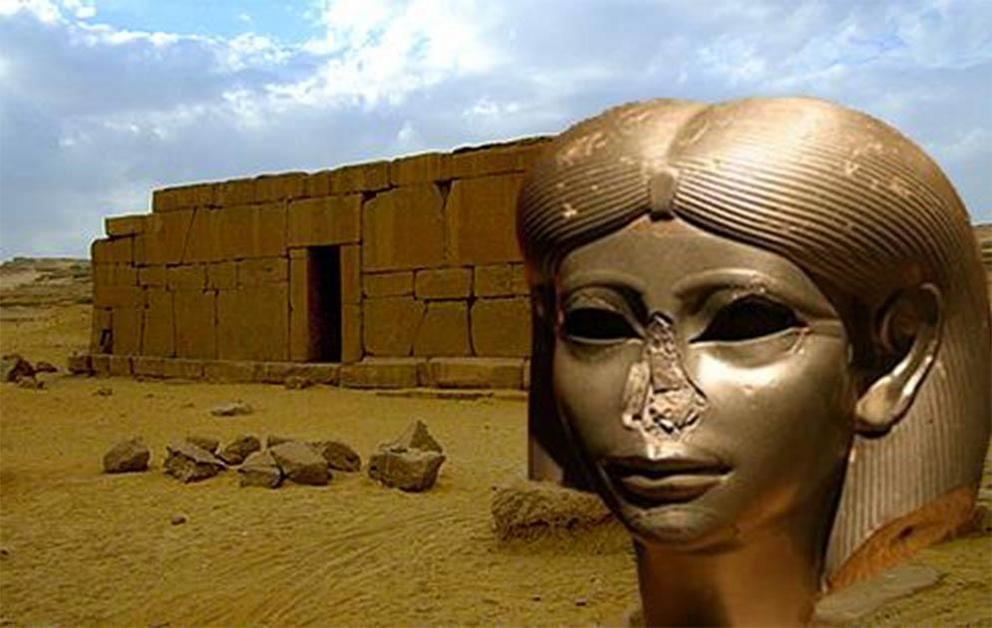

Top Image: The Qasr el-Sagha temple. Insert: Head of an ancient Egyptian royal daughter dating to around 1850 BC thought to be Sobekneferu.

In part one , we saw how Egypt’s first female pharaoh Sobekneferu (also written Neferusobek) has emerged as a major character both in literary fiction and in the cinema. Her mysterious life and devotion to primeval gods such as the crocodile god Sobek no doubt helped foster this romantic image. Despite this, Sobekneferu’s achievements in life remain an enigma. We know she might have shared the throne with her father, the powerful pharaoh Amenemhat III, and that following his death she probably entered into an incestuous relationship with her brother Amenemhat IV. Her own brief reign of just four years ended Egypt’s Twelfth Dynasty, although what became of her is unclear. Whether Egypt’s first female pharaoh died of natural causes or met a sticky end is nowhere recorded.

Artist impression of Sobekneferu by London artist Russell M. Hossain.

Artist impression of Sobekneferu by London artist Russell M. Hossain.

City of the Crocodiles

To better understand Sobekneferu’s lasting legacy we will need to examine monuments directly or indirectly associated with her, for these can provide certain clues regarding her actions in life. We go first to the El-Faiyum Oasis , her seat of power around 80 kilometers (50 miles) south of Giza. Here next to Birket Quran, the Lake Moeris of antiquity, was the city of Shedet, called by the Greeks Crocodopolis, the city of crocodiles. Founded originally by the first king of the Twelfth Dynasty, Amenemhat I, it would later become the center for the worship of the crocodile god Sobek during the reigns of Amenemhat III and his daughter Sobekneferu. This included a temple in which a live crocodile was worshipped as an incarnate form of the god.

The Labyrinth

The site of Crocodopolis corresponds with what is today the city of Medinet el-Faiyum in the heart of the El-Faiyum Oasis. Seven kilometers (4 miles) to the southeast is Hawara, the site of a pyramid complex built by Amenemhat III. Immediately to the south of the main pyramid the king commissioned the construction of an enormous funerary monument named Amenemhat-ankh, the “Life of Amenemhat.” Various inscriptions found at the site tell us that Sobekneferu added to the existing monument during her own reign.

The Greek historian Herodotus (484-425 BC), who visited Egypt around 455 BC, saw this vast complex for himself on a trip to Lake Moeris. He wrote that, “no words can tell its wonders … were all that Greeks have builded and wrought added together the whole would be seen to be a matter of less labour and cost than was this labyrinth ,” adding that it had around 1500 double sets of chambers making 3000 in total, and that beneath ground there were underground chambers containing “the burial vaults of the kings who first built this labyrinth, and [those] of the sacred crocodiles ( Histories, II, 148 ).”

Amenemhat III’s pyramid at Hawara.

Amenemhat III’s pyramid at Hawara.

The presence inside Egypt’s great Labyrinth, as it became known, of sacred crocodiles makes it clear Sobek was its chief god. Indeed, excavations carried out there in 1910 by British archaeologist Sir Finders Petrie (1853-1942) uncovered several statues and reliefs of Sobek ( Petrie, 1912, 31-32), confirming his role as its principal deity.

The site of the Egyptian Labyrinth today.

The site of the Egyptian Labyrinth today.

Crocodiles seen on a limestone block at the site of the Labyrinth at Hawara representing the power of the god Sobek.

Crocodiles seen on a limestone block at the site of the Labyrinth at Hawara representing the power of the god Sobek.

The Mazghuna Pyramids

Despite the El-Faiyum Oasis being seen as the sacred domain of the crocodile god, Sobekneferu made the decision not to be buried near her father’s pyramid complex at Hawara. She chose instead a site close to Amenemhet III’s other pyramid complex at Dahshur (its ruined pyramid is known today as the Black Pyramid).

The location is in the desert close to the village of Mazghuna, which lies on the western edge of the Nile valley some 60 kilometers (38 miles) northeast of Hawara. Here Sobekneferu would appear to have been involved in the construction of two pyramids – one intended as her sepulcher and another, a quarter of a mile (400 meters) to the south, meant for her brother Amenemhat IV.

Both Mazghuna pyramids were investigated in 1910 by British archaeologist Ernest Mackay (Mackay, in Petrie, 1912 ). He reported that they had been constructed wholly of limestone blocks, in contrast to other pyramids of the Middle Kingdom, which (with one exception) were built of mud bricks and encased with limestone. Yet in both cases – Mazghuna North and Mazghuna South – the pyramids had been utterly destroyed in antiquity, leaving behind a large area of limestone chips, beneath which Mackay found virtually intact sub-structures cut deep into the bedrock. Both pyramids possess finely carved descending corridors with intricate sub-chambers and stairways. Mazghuna North is the more accomplished of the two, with Mazghuna South being considered a poorer quality variant of its northern counterpart (Mackay, in Petrie, 1912 ).

Sobekneferu is generally attributed the Mazghuna North pyramid ( Theis, 2009 ), while her brother, Amenemhat IV, is usually linked with the Mazghuna South pyramid. That said, no artifacts from their reigns have been found in direct connection with either pyramid, making these attributions tentative to say the least. The association with the reigns of both kings comes from structural similarities between the internal architecture of the Mazghuna pyramids and that of Amenemhat III’s pyramid at Hawara. They include the unique use of enormous quartzite blocks to create the monolithic sarcophagus chambers seen in all three of these pyramids ( Lucas, 1999, 63).

Internal sub-structure of the Mazghuna North pyramid built for Sobekneferu.

Internal sub-structure of the Mazghuna North pyramid built for Sobekneferu.

The Cult of Sobekneferu, Egypt’s First Female Pharaoh

Despite no objects from the reigns of either Sobekneferu or Amenemhat IV having been found in association with the Mazghuna pyramids, and no hard evidence they were ever interred in them, a Thirteenth Dynasty stele found in the vicinity speaks of Sobekneferu being venerated at the site as a divinity ( Theis, 2009 ). The existence of this inscription (known as Marseilles No. 223) shows not only that in death she was considered divine (just as her father was proclaimed before her), but also that her assumed resting place was indeed at Mazghuna.

The kings of the Thirteenth Dynasty certainly believed that Sobekneferu was interred at Mazghuna. Yet if she was not buried in her intended pyramid, what happened to her? Following the collapse of the Twelfth Dynasty it is quite likely that Egypt was plunged into a state of turmoil with various politico-religious factions vying for control, each attempting to justify its own chosen candidate for kingship.

Some of these factions would have been opposed to Sobekneferu and any remnant of her outgoing dynasty. This might have prompted those still loyal to her royal line to secretly hide her body, and that of her brother. If correct this would adequately explain why neither ruler was interred in the pyramid prepared for them.

Do the mummies of Sobekneferu and her brother await discovery in the desert sands or low hills west of Mazghuna, or were they destroyed long ago? All that can be said with any degree of certainty is that to the kings of the Thirteenth Dynasty the spirit of Sobekneferu could be felt close to her pyramid at Mazghuna, the site of which is today marked by a small Coptic cemetery that has become the stuff of mystery and imagination (it features, for instance, in the 1986 thriller The Mummy Case by Elizabeth Peters ).

View of the Mazghuna landscape from the position of the south pyramid, the opening to which is seen in the foreground.

View of the Mazghuna landscape from the position of the south pyramid, the opening to which is seen in the foreground.

Yet if Sobekneferu really had chosen Mazghuna as her final resting place, it is important to understand why. Was it simply because it was close to her father’s second pyramid complex at Dahshur, or was there some other more profound reason for choosing this location? To answer this question we need to leave Mazghuna behind for the time being, and journey 56 kilometers (35 miles) east-southeastwards to a remote location around 8 kilometers (5 miles) north of Lake Quran’s current shoreline. For here, in a remote desert environment, is arguably one of the strangest and most enigmatic monuments in the whole of Egypt.

The Qasr el-Sagha Temple

I refer to the extraordinary megalithic temple of Qasr el-Sagha (meaning “Fortress of Gold”) situated above the former northern shoreline of Lake Quran at the base of an east-west aligned hill ridge of the same name. This itself forms the southern extent of the Gebel Qatrani formation, which caps the mountainous skyline to the north of the El-Faiyum basin. During the Fourth and Fifth Dynasties (circa 2613-2345 BC) black basalt from a quarry site named Widan el-Faras, on the top of the escarpment, was used to create the paved floors of mortuary temples built next to various pyramids including the Great Pyramid at Giza.

Made of huge polygonal blocks of limestone, the interior of the Qasr el-Sagha temple has seven chambers on its northern side, each linked to a long offering hall that opens into two further chambers, one at each end. An isolated tenth chamber can only be accessed from above as it has no entrance doorway.

The Qasr el-Sagha temple was probably built during the reigns either of Amenemhat IV or of Egypt’s first female pharaoh, Sobekneferu, in honor of the crocodile god Sobek.

The Qasr el-Sagha temple was probably built during the reigns either of Amenemhat IV or of Egypt’s first female pharaoh, Sobekneferu, in honor of the crocodile god Sobek.

Architecturally, the Qasr el-Sagha temple seems to resemble very similar megalithic structures seen at Giza to the north. These also employed the use of polygonal masonry. They include the Valley Temple of Khafre and the nearby Temple of the Sphinx, both built towards the end of the Fourth Dynasty (circa 2500 BC). It is for this reason that early explorers who saw the Qasr el-Sagha temple thought it was constructed during the Old Kingdom period.

However, its proximity to Twelfth and Thirteenth Dynasty settlements built on the lake’s northern shoreline has now led to the conclusion that it was probably a temple of Sobek constructed during the reigns either of Sobekneferu or Amenemhat IV ( Shaw 2004, 66, although a construction date during the reign of Twelfth Dynasty king Senusret II has also been proposed. See Ibid.)

The temple’s main axes may help throw more light on its construction. The structure’s long axis, for instance, oriented approximately 20.3 degrees north of east, targets, at a distance of 56 kilometers (35 miles), the Mazghuna North pyramid (see accompanying illustration). This finding immediately links the two monuments with Sobekneferu, and therefore seems unlikely to be a coincidence.

If we look now at the Qasr el-Sagha temple’s short axis, which is approximately 20.3 degrees west of north, we find that it marks the setting around 1800 BC, the timeframe of Sobekneferu, of the star Eltanin, which would have been seen to descend into the summit of the Gebel Qatrani formation. So why might stellar alignments have been important to Egypt’s first female ruler?

Map showing the landscape geometry linking the Qasr el-Sagha temple with the setting of the star Eltanin in 1800 BC, the Mazghuna North pyramid and both the Red Pyramid of Dahshur and the Great Pyramid of Giza.

Map showing the landscape geometry linking the Qasr el-Sagha temple with the setting of the star Eltanin in 1800 BC, the Mazghuna North pyramid and both the Red Pyramid of Dahshur and the Great Pyramid of Giza.

The Crocodile Star

Otherwise known as Gamma Draconis (γ Dra), Eltanin is a giant orange star located in the head of the constellation of Draco, the monster Typhon of Greek astronomy. The name Eltanin derives from Arab star lore and is thought to refer to the asterism as a whole, with el-tannin, in Aramaic and modern Hebrew, meaning a sea-monster, dragon, or crocodile ( Koehler and Baumgartner, 1993, vol. 2 ). As we saw in part one of this feature, the ancient Egyptians saw the stars of Draco as a sky figure in the form of a hippopotamus ( the goddess Taweret or Reret) and/or a crocodile (the god Sobek), both creatures often being combined into a single chimera-like hybrid.

The constellation of Draco shown as a serpent with the star Eltanin on the creature’s forehead.

The constellation of Draco shown as a serpent with the star Eltanin on the creature’s forehead.

It was the English scientist and astronomer Sir Joseph Norman Lockyer (1836-1920) who first noted Eltanin’s importance in ancient Egyptian astronomy. In his book The Dawn of Astronomy (1894) he observed that several Egyptian temples were oriented towards the rising of the star Eltanin. Lockyer suspected Eltanin only became important in Egypt after axial precession – the slow wobble of the earth across an approximately 26,000-year cycle – caused the star to begin setting briefly before almost immediately rising again. Like modern scholars, Lockyer proposed that dynastic Egyptians saw Draco either as a hippopotamus or as a crocodile ( Lockyer, 1894, 146-153). Eltanin formed some part of its head, most obviously an eye or an orange carbuncle placed in its forehead, which each night would dip beneath the horizon before rising again.

Thus the Qasr el-Sagha temple was aligned via its short axis with a bright orange star identified with the crocodile god Sobek. Interestingly, the Coffin Texts , which are spells and magic formulas found on burial coffins during Egypt’s First Intermediate period and afterwards during the Middle Kingdom, thus circa 2181-1650 BC, make reference to an influential star that might be Eltanin. It is found in Spell 148, which states, “The crocodile star ( ky sšd ) strikes … Isis wakes pregnant with the seed of Osiris – namely Horus” ( Gadalla, 2016 , 35).

Although other interpretations of the term ky sšd are possible (see Faulkner, 1968 ), the likelihood is that during the age of Sobekneferu there was a belief in the existence of a single star representative of the powers of Sobek, and if this was the case then there seems every reason to suspect this “crocodile star” was Eltanin, its orange hue reflecting the fact that Sobek was associated with an otherworldly temple made of carnelian, with carnelian being a semiprecious stone, orange in color, that was of great importance in ancient Egyptian funerary rites. Interestingly, the only confirmed bust of Sobekneferu shows the queen wearing a pendant in the shape of a heart, which may be the same one shown around the neck of her father. These heart pendants were usually made of carnelian – a tentative link perhaps to Sobek’s carnelian temple and Eltanin’s role as the Crocodile Star? The star’s distinct orange appearance only adds to this conclusion.

Bust of Sobekneferu on display in the Louvre, Paris.

Bust of Sobekneferu on display in the Louvre, Paris.

Aligning with the Ancestors

The question remains as to why the Qasr el-Sagha temple was built in the architectural style of Old Kingdom buildings such as Giza’s Valley Temple of Khafre? The answer must lie in the Twelfth Dynasty’s wish to connect its kings with the renowned pyramid builders of the Old Kingdom. For instance, Amenemhat I, the founder of the dynasty, attempted to legitimize his rule by linking himself with the ancestral memory of the kings of the Old Kingdom. Backing up this hypothesis is the fact that red granite blocks from Khafre’s complex at Giza were sequestered for use in the construction of Amenemhat I’s pyramid at Lisht for no good reason other than their “spiritual efficacy” ( Lehner, 1997, 168).

Further possible confirmation of this surmise comes from the fact that if the axial alignment between the Qasr el-Sagha Temple and the Mazghuna North pyramid is extended tangentially north-northwestwards it targets the peaks both of the Red Pyramid of Dahshur, attributed to Sneferu, Khufu’s father, and, distantly, the Great Pyramid, Khufu’s own sepulchral monument at Giza. This means that as viewed from the Mazghuna North pyramid the star Eltanin would have been seen to set down into the peak of the Red Pyramid of Dahshur, behind and beyond which would have been the Great Pyramid .

Sobek the Creator

This synchronization both with Old Kingdom monuments and with the setting of the suspected Crocodile Star Eltanin strongly suggests that the celestial influence of Sobek was important to the rulers of the Twelfth Dynasty. At this time Sobek was seen as a creator god, equal in importance with the sun-god Re. Sobek’s acknowledged place of creation, as well as the point of renewal of the world each day, was the El-Faiyum Oasis, the story as told in a Ptolemaic textual work known today as the Book of the Faiyum. Not only does it show Sobek as a crocodile on the back of his wife, the hippopotamus goddess Taweret, mimicking the sky figure represented by the stars of Draco, Ursa Minor and Ursa Major (see illustration), but there is every reason to conclude that this important work derives from mythological themes originating in the El-Faiyum Oasis as early as the Twelfth Dynasty.

Left, Sobek as crocodile and Taweret as hippopotamus from the Book of the Faiyum and, right, the crocodile and hippo sky figure as seen in the tomb of Seti I, the latter representing the stars of Draco, Ursa Minor and perhaps Ursa Major.

Left, Sobek as crocodile and Taweret as hippopotamus from the Book of the Faiyum and, right, the crocodile and hippo sky figure as seen in the tomb of Seti I, the latter representing the stars of Draco, Ursa Minor and perhaps Ursa Major.

In the third and final part of this feature we look at Sobekneferu’s own unwritten background, and in particular her potential Semitic links, bringing us even closer to understanding the true nature of her faith in primeval gods and Egypt’s most ancient magics.