Pavlopetri: 5,000-year-old town discovered underwater in Greece

Top Image: The University of Nottingham conducted a research project at Pavlopetri which combined archaeology, underwater robotics and state-of-the-art graphics. This allowed them to generate stunning images to rebuild the ruined town. Here you can see the underwater remains and the digitally reconstructed pillars and walls of one of the buildings.

Nothing sparks the imagination of history enthusiasts quite like underwater discoveries, ranging from sunken cities to the millions of shipwrecks still unexplored on the seabed. The bottom of the seas and oceans of the world have been described as the biggest museum of the world, with less than 1% of the ocean floor having been surveyed to date. The remains of the Bronze Age port of Pavlopetri were discovered as recently as the 1960s and some argue that they may have been the basis for the legendary story of Atlantis.

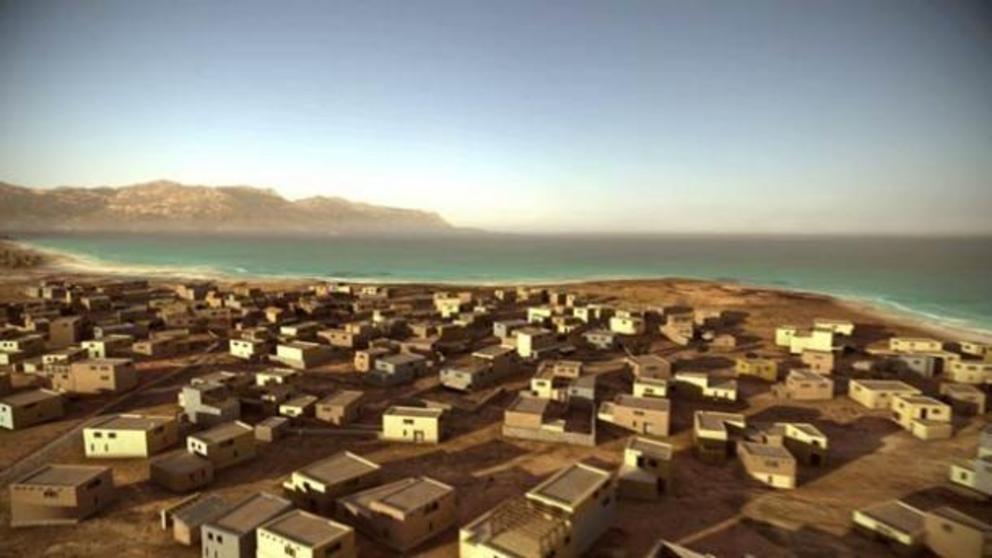

The ruins of Pavlopetri are located a short distance from the coastline, just a few meters underwater in Vatika Bay in southern Greece.

The ruins of Pavlopetri are located a short distance from the coastline, just a few meters underwater in Vatika Bay in southern Greece.

Discovery of Pavlopetri: The Oldest Underwater Town in the World

In the 1960s, Nic Flemming from the Institute of Oceanography at the University of Southampton, rediscovered the remains of a submerged settlement believed to date back as far as 5,000 years ago. Located in the Peloponnesus region of southern Greece, near a small village called Pavlopetri, the archaeological site lies 4 meters (13.12 ft) underwater and is now believed to be the oldest known planned underwater town in the world. It therefore joined the ranks of other mysterious underwater settlements, towns, and cities which have captured the imagination of history enthusiasts including:

- The perfectly preserved ancient Chinese city of Shi Cheng (the Lion City)

- The mythical submerged temples of Mahabalipuram in India

- The ancient Egyptian city of Heracleion

- The 9,000-year-old Neolithic site of Atlit Yam in Israel

- The 17th century pirate city of Port Royal , Jamaica

Could the Pavlopetri site in southern Greece have been the inspiration for Plato’s story of Atlantis?

Could the Pavlopetri site in southern Greece have been the inspiration for Plato’s story of Atlantis?

The site had been originally identified by the geologist Folkion Negris in 1904, but after Flemming rediscovered the site, it was surveyed in 1968 by a team of archaeologists from the University of Cambridge. Then in 2009, under the direction of John C. Henderson, the University of Nottingham began a five-year project with the Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities of the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Tourism and the Hellenic Centre for Marine Research to study the town at Pavlopetri.

The resulting Pavlopetri Underwater Archaeology Project used a novel combination of archaeology, underwater robotics and state-of-the-art graphics to survey the seabed and bring the ancient town back to life before the fragile remains are lost forever due to lack of protection, pollution, waves, currents, and tourism. Thanks to the project, Pavlopetri became the first underwater town to be digitally surveyed in 3D using sonar mapping technology . This fusion of cutting edge marine technology and movie industry computer graphics allowed them to generate stunning photorealistic 3D digital reconstruction images which revolutionized underwater archaeology.

The resulting research project used a novel combination of archaeology, underwater robotics, and state-of-the-art graphics to survey the seabed and bring the ancient town back to life.

The resulting research project used a novel combination of archaeology, underwater robotics, and state-of-the-art graphics to survey the seabed and bring the ancient town back to life.

What Did They Find at Pavlopetri?

The research project identified thousands of artifacts at the site which help create a deeper understanding of everyday life at Pavlopetri from about 3000 BC until it “sank” around 1100 BC, probably due to earthquakes that are common in the region, erosion, rising sea levels, or even a tsunami. The remains are the first of a sunken city in Greece that predates Plato’s story of Atlantis.

As a snapshot of life 5,000 years ago, Pavlopetri was incredibly well designed with roads, two storey houses with gardens, temples, a cemetery, and a complex water management system including channels and water pipes. In the center of the city, there was even a square or plaza measuring about 40 by 20 meters (131 x 65 ft) and most of the buildings had up to 12 rooms inside. “There are older sunken sites in the world but none can be considered to be planned towns such as this, which is why it is unique,” explained Dr. Jon Henderson, from the University of Nottingham team who managed the Pavlopetri Underwater Archaeology Project, in The Guardian .

The city is so old that it existed in the period that the famed ancient Greek epic poem Iliad was set in. Research in 2009 revealed that the site extends for about 9 acres (36,421 m2) and evidence shows that it had been inhabited prior to 2800 BC. Despite sinking so long ago, the arrangement of the city is still clearly visible and at least 15 buildings have been found. The city’s arrangement is so clear that the head of the archaeological team from Nottingham were able to create what they believe is an extremely accurate 3D reconstruction of the city.

Historians believe that the ancient city was a center for commerce for the Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations. Scattered all over the site there are large storage containers made from clay, statues, everyday tools, and other artifacts.

The original name of the city is unknown, as well as its exact role in the ancient world. “It’s a rare find, and it is significant because, as a submerged site, it was never reoccupied and therefore represents a frozen moment of the past,” explained Elias Spondylis of the Greek Ministry of Culture in the New Scientist .

A digital reconstruction of the buildings at Pavlopetri being submerged by the sea about 1100 BC.

A digital reconstruction of the buildings at Pavlopetri being submerged by the sea about 1100 BC.

Pavlopetri Today

Probably the most surveyed seabed in the world, the coverage the Pavlopetri site has been channeled into protecting the archaeological remains. In 2011, the BBC produced a stunning documentary entitled Pavlopetri – The City Beneath the Waves , which focused on the way technology was used by the University of Nottingham team to create a photorealistic impression of the seabed. In 2016 Pavlopetri was included on the World Monuments Watch , a global program which works to protect heritage locations under threat, to support local conservation and protection efforts - which included a Watch Day organized by the Greek Chapter of ARCH International to raise awareness about the site.

Since then the Watch Day has incorporated the Pavlopetri Eco-Marine Film Festival , which showcases films and documentaries about the marine environment, as well as underwater snorkel tours over the ancient city. Thanks to these actions, in August 2016 the area was demarcated by buoys to protect it from small vessels and in 2018 the site became the first in Greek waters to be included in marine charts provided to mariners by the Hydrographic Service of the Greek Navy.