Genetic study suggests Denisovans were the mythological Rakshasas

Mythological, demonic Rakshasa

A new genetic study of 1739 Asian individuals from 219 populations has found that on the Indian sub-continent today Denisovan DNA exists mostly among isolated, tribal communities. It also found that considerably less Denisovan ancestry exists among Asians in India and Pakistan of clear Indo-European descent. Yet the greater implications of these findings relate to the possible presence in South Asia in the distant past of Denisovans, who in Indian mythology may well be remembered as blood thirtsy demons known as the Rakshasas.

The study, which was led by US and Asian scientists from Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, the National Institute of Biomedical Genomics (NIBG), Kalyani, India, and the University of California in the USA, was undertaken primarily to correct what was seen as a non-Asian bias in genetic research. Its findings will have implications for our understanding of the formation of the population of Asia and, through gene inheritance, on medicine and healthcare in the region.

According to Partha P. Majumder, the founder of NIBG, and one of the co-authors of the new paper published in Nature, the study is the most extensive so far of Asian DNA and comes as a response to a previous absence of data about the Asian genome.

This is highlighted by the fact that currently available genome data is derived from DNA chips – microchips that hold DNA probes forming half the DNA double helix that can recognize DNA from samples tested. These are normally optimized for Caucasian populations. They can therefore give false information regarding Asian genomes, which are noticeably different.

Map showing the locations of Asian populations featured in the new study, along with the total number of individuals from each area.

Map showing the locations of Asian populations featured in the new study, along with the total number of individuals from each area.

Study Objectives

Majumder explains that the objectives of the study – seen as the pilot phase of the GenomeAsia 100K Project – was to generate and catalogue DNA sequencing and variation on a large population of Asian individuals. In addition to this, it was to determine whether insights might be determined from whole-genome sequence of databases, while, finally, relevant medical conclusions would be drawn from the data produced.

Majumder explains that the new data is important to discover genes associated with diseases common among Asian populations. Proteins are also important since changes in protein are related to diseases. For instance, it was discovered that among Asian populations tested, a DNA variant in a gene (NEUROD1) was present, and this has been linked to a particular kind of diabetes. Another DNA variant in the hemoglobin gene linked to beta-thalassemia was found only among South Indians. Most notable was the finding that Carbamazepine, an anti-convulsant used to treat medical disorders, could well have adverse effects in about 400 million southeastern Asians who form part of the Austronesian language group.

Beyond the findings regarding genes associated with diseases specific to Asian populations, the study also looked at the genetic background behind the emergence, cultural spread and geographical placement of these same populations, with particular emphasis to those living in the Indian sub-continent.

Non-Indo-European Languages

Majumder and his team found that in India indigenous tribal and non-Indo-European-speaking populations possessed the highest amounts of Denisovan DNA, adding that it was less evident among ‘upper’ caste groups. Indo-European speakers, particularly those of Pakistan, faired worse with the lowest recorded Denisovan component of all groups. These results were obtained by correlating the level of Denisovan DNA with an individual’s language, as well as their social and caste status. In addition to this, the Denisovan ancestry of individuals who spoke Indo-European languages was matched against those who spoke non-Indo-European languages, such as the Dravidian group of languages , spoken by more than 215 million people, all mostly in southern India and northern Sri Lanka.

Indigenous tribal people of India had the highest amounts of Denisovan DNA

Indigenous tribal people of India had the highest amounts of Denisovan DNA

What the team found was that the average levels of Denisovan ancestry were significantly different between the four social or cultural groups consistent with the fact that Indo-European-speaking migrants, who are generally considered to have entered the Indian subcontinent from the northwest, admixed with an indigenous South Asian group or groups who not only possessed higher levels of Denisovan ancestry, but also spoke non Indo-European languages.

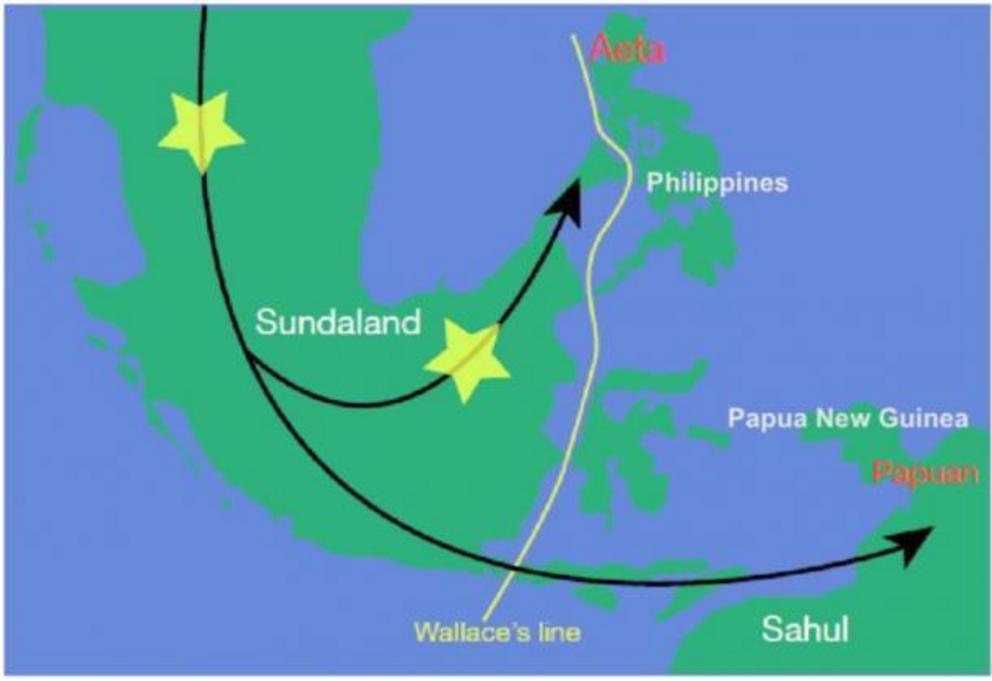

Next, the study team matched the genetic markers of the Denisovan ancestry found among the indigenous populations of the Indian sub-continent with that of Denisovan types, this being broken down into the Siberian Denisovans - typified by the genome of the hominid fossil remains from the Denisova Cave in Siberia, as well as in modern populations in places like China - and the so-called Sunda Denosovans. They are thought to have thrived in the former Sunda landmass, which combined the Malaysian peninsular with the islands of Indonesia through till the end of the last ice age.

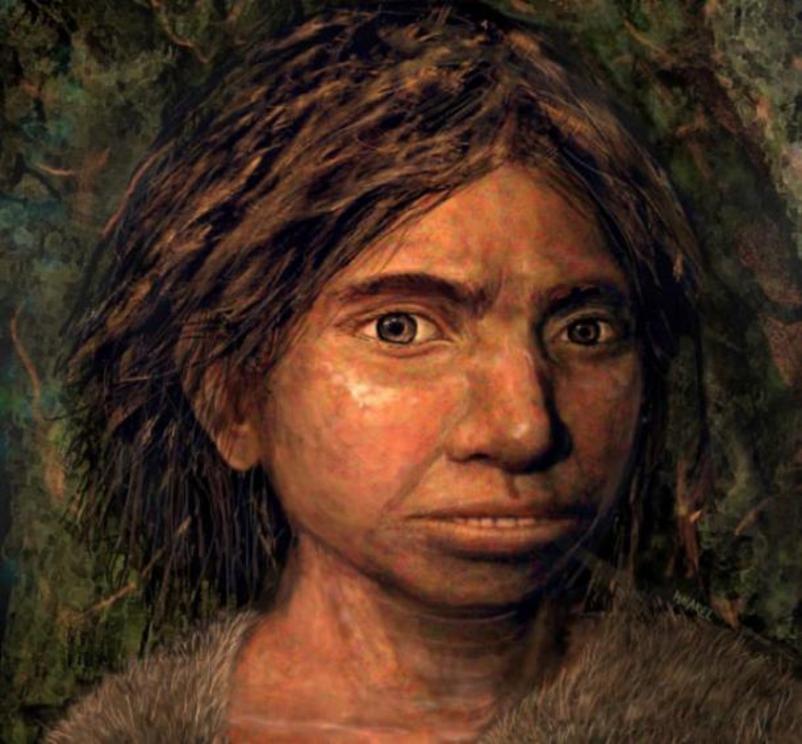

Portrait of a juvenile Denisovan based on a skeletal profile reconstructed from ancient DNA methylation maps.

Portrait of a juvenile Denisovan based on a skeletal profile reconstructed from ancient DNA methylation maps.

Sunda Denisovan Ancestry

What Majumder and his team found was that the Denisovan ancestry present among the indigenous populations of the Indian sub-continent was that of the Sunda Denisovans, and not their northern cousins, who probably thrived in Siberia, Mongolia, the Tibetan Plateau and eastern Asia, most obviously northern China.

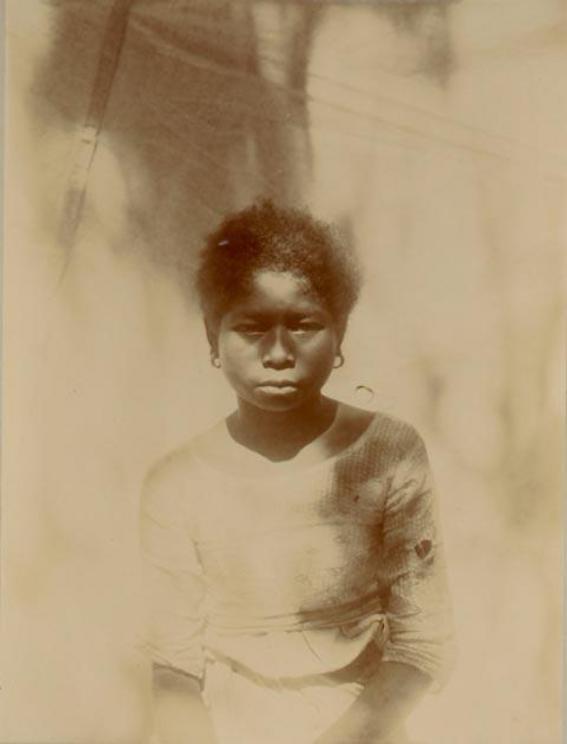

The Denisovan DNA in the South Asian populations was consistent with that found also among the Melanesians of Papua New Guinea and the Aeta, a Negrito tribal society from Luzon Island in the Philippines, even though with them the level of Denisovan ancestry was considerably higher. This led the study to conclude that introgression between Sunda Denisovans and the earliest anatomical modern humans to reach the region most likely occurred somewhere in the vicinity of the former Sunda landmass, where Denisovan ancestry remains strongest to this day. Since the same Denisovan DNA is found among the indigenous peoples of the Indian sub-continent, Majumder and his team surmise that after this introgression took place in southeastern Asia, modern humans now carrying Denisovan ancestry, traveled westward, entering and settling in South Asia, explaining the high levels of Denisovan DNA recorded among the pre-Indo-European inhabitants of the Indian sub-continent today.

A Second Introgression

Majumder and his team also highlight the fact that, in addition to the high levels of Denisovan ancestry among both Melanesians and the Aeta, consistent with an admixture event common to both them and South Asians, the Aeta additionally display Denisovan mitochondrial haplogroups that are unique to their population. This suggests that a second admixture event between the Aeta and Denisovans must have occurred after the separation of the Aeta and Melanesians, perhaps even as recently as 20,000 years ago. A suggestion of this second admixture event involving Denisovans and indigenous peoples of Indonesia and the Philippines had previously been found during the course of a separate study announced earlier this year. This at the time prompted the theory that there were not just two basic types of Denisovan – the Siberian Denisovan and Sunda Denisovan, but also a third type, which was most likely a breakaway from the Sunda Denisovans.

Suggested places of first contact between modern humans and Denisovans in the area of the former Sunda landmass according to Majumder and his colleagues.

Suggested places of first contact between modern humans and Denisovans in the area of the former Sunda landmass according to Majumder and his colleagues.

All this information is good news for our understanding not only of the introgression between Denisovans and modern humans, but also as to where and when exactly this might have taken place. That said, Majumder and his team’s assumption that the primary cause of high levels of Denisovan DNA among South Asians is because modern humans who had encountered Denisovans within the Sunda landmass then migrated westwards now carrying Denisovan ancestry might well only be half the story.

If this was the case then why would the Negrito population of the Andaman Islands off the Bay of Bengal, who share genetic traits in similar with the Aeta of the Philippines, possess no traceable Denisovan ancestry? Surely if the Denisovan-DNA-carrying ancestors of the Aeta Negritos of the Philippines, or indeed the Melanesians of Papua New Guinea, migrated westwards they would have left evidence of their presence among the indigenous Negrito tribes in places like the Andaman Islands, but this is simply not the case. No Denisovan DNA can be found among Andaman Islanders . A counter argument, of course, would be that the Denisovan-modern human hybrids of southeastern Asia migrated overland, missing the Andaman Islands altogether.

Female of an Aeta tribe, the Negrito population of the island of Luzon in the Philippines.

Female of an Aeta tribe, the Negrito population of the island of Luzon in the Philippines.

Another, and in my opinion more likely scenario explaining the presence of Denisovan DNA among indigenous South Asians is that our earliest modern human ancestors migrating out of Africa some 60,000-70,000 years ago crossed the Arabian peninsular and entered South Asia via Pakistan. Either here or further into the Indian sub-continent, most obviously in India itself, they encountered Sunda Denisovans who had been inhabiting the region for tens if not hundreds or thousands of years. Here introgression took place. These hybrid humans, now carrying Denisovan DNA, then continued their migrational journey eastwards into southeastern Asia encountering further Denisovans along the way, each time interbreeding with them. Finally, they would have reached the edge of the Eurasian landmass. Here they became the earliest ancestors of, among others, the inhabitants of the Sunda landmass, as well as the Aeta of the Philippines, and the Melanesians of Papua New Guinea, which was at the time part of an enormous island continent with Australia to the south called Sahul. When all this might have taken place is open to speculation, although undoubtedly it occurred no later than 45,000-60,000 years ago, with further waves of migration continuing through till around 20,000 years ago.

Map showing migrational routes of modern humans out of Africa from around 65,000 years ago onwards. The circles signify the percentages of Denisovan DNA among modern populations (the higher the percentage, the larger the circle), while the north-south div

Map showing migrational routes of modern humans out of Africa from around 65,000 years ago onwards. The circles signify the percentages of Denisovan DNA among modern populations (the higher the percentage, the larger the circle), while the north-south div

The Rakshasas

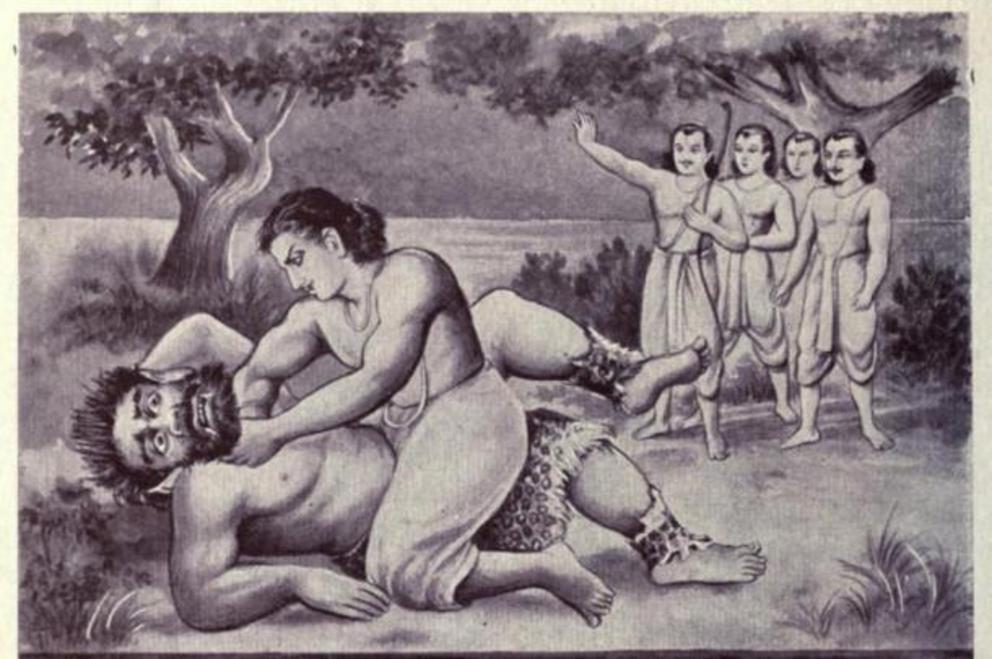

Once again, there are some short falls with this theory, the distinct lack of Denisovan DNA among Andaman Islanders being just one, but this alternative scenario not only makes good sense, but also hints at the presence of Sunda Denisovan in the Indian sub-continent, their suspected great size, alleged grotesque appearance in the eyes of modern humans, and perhaps even their uncouth dietary habits causing them to be remembered in mythology as the Rakshasas. These were demon-like creatures, often synonymous with the Asuras, who in Vedic literature were said to have been created from the breath of Brahma when sleeping, an event that occurred at the end of the Satya Yuga . This was the first of the four yuga cycles, which was said to have lasted 1,728,000 years (we are currently at the end of the fourth and final cycle known as the Kali Yuga. A new Satya Yuga will follow afterwards).

It was said that as soon as the Rakshasas were created they were so consumed with bloodlust that they even started to eat Brahma himself! He in turn shouted "Rakshama!" (Sanskrit for "Protect me!") at which the god Vishnu appeared, coming to Brahma’s aid and banishing to earth all Rakshasas, who therefore bear a name derived from Brahma’s cry for help.

Death of the rakshasa Hidimba as illustrated in an edition of the Mahabharata epic. He was said to have been 8 cubits (4 meters) tall.

Death of the rakshasa Hidimba as illustrated in an edition of the Mahabharata epic. He was said to have been 8 cubits (4 meters) tall.

As phantasmagorical as the Rakshasas clearly are, their presence in this world prior to the emergence of the first human dynasties suggests they are the memory, as debased as it might have become, of an archaic human group that once inhabited the Indian Sub-continent. If so, then the most likely real life counterparts of the Rakshasas were the Denisovans, who existed throughout the eastern half of the Eurasian subcontinent for hundreds of thousands of years, their final survivors perhaps encountering indigenous peoples like the Aeta of the Philippines as recently as 20,000 years ago.